Turning Points

My seventy-fourth birthday rolled by this month. I’ve been looking back since then and thinking about turning points. There are so many and they go way back.

I almost failed the second grade. I was in love with Mrs. Halper, but her weekly spelling tests broke my heart. She called out eight words. We scrawled the letters in cursive. She collected the papers, circled in red the ones we got wrong, and handed them back to us. My paper was always the bottom score in the class. Almost all my words were circled, test after test.

Half-way through the school year, Mrs. Halper told Mom she couldn’t pass me to the third grade unless I learned to spell. They settled on a plan. Mrs. Halper drew up a big list of words each week. She worked with me on it after school, then Mom sat with me at the kitchen table each night. She called out the words. I wrote them down. She corrected them, and we did them again. And again.

I can’t pinpoint the moment or explain how it happened, but somewhere along the line, I began to develop a feel for the art of orthography and its maddening inconsistencies. I got four right on a test in February. Five the next week. Six a month later. Mom cheered when I brought that one home.

The big moment came the week before Easter. Mrs. Halper called out the eight words. I wrote them down. During nap time, I peeked through my fingers at Mrs. Halper as she graded our tests. A few minutes into it, she laid down her red pen, dabbed at her pretty blue eyes with a tissue, then smiled at me through tears. Later that day, she thumbtacked my paper to the bulletin board, and when we went out to recess, she kissed me on the cheek. I almost fainted.

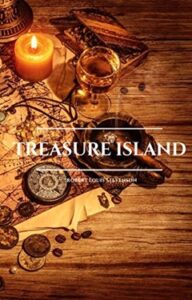

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

“I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea-chest following behind him in a hand-barrow — a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man, his tarry pigtail falling over the shoulder of his soiled blue coat, his hands ragged and scarred, with black, broken nails, and the sabre cut across one cheek, a dirty, livid white. I remember him looking round the cover and whistling to himself as he did so, and then breaking out in that old sea-song that he sang so often afterwards: Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest —/Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!”

I could see Billy Bones and hear him singing as clearly as if he’d walked into my bedroom. Mesmerized, I read on for hours. Jim, Long John, and the pirates took me across the seas in search of buried treasure, and I never returned. Treasure Island became the first leg of a life-long journey borne on the wings of artfully told stories, wending my way through a thousand worlds to a B.A. in English Literature, through careers in teaching, law, and business, to come to rest in my seventh decade in Whippoorwill Hollow.

One of the worlds I visited along the way was Denmark’s Elsinore Castle in the Middle Ages. When I was seventeen, I walked on unsteady legs to the front of the room and stood before my classmates, high school seniors, sitting in rows of desks, all looking at me, waiting.

Each of us had to recite from memory the soliloquy from Act I, scene ii of Hamlet, 31 lines, 259 words. Presenting it without faltering would be enough to secure a good grade, but I wanted to do more than that. Hamlet was a sad, conflicted prince, plagued with self-doubt and self-loathing. Struggling with world-class adolescent insecurities, I felt Hamlet’s anguish and thought I could give his troubled heart a voice if I could find the courage to bare my soul in front of my friends, but courage wasn’t my strong suit. Up to that point, I’d never taken center stage or done anything to set myself apart. I preferred to hide in the shadows where it was safe, but that day, inspired by Shakespeare and a gifted teacher, Mr. Turner, I desperately wanted to step forward into the light.

Feeling vulnerable in front of my classmates, I fixed my gaze on reddish-gold spears of autumn sunlight coming through the back windows, then took a deep breath, and held my trembling hands up before me. “Oh that this too, too solid flesh would melt,/Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew.” My voice broke, then steadied as Hamlet’s sorrow swelled up inside me and took control. “How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable/Seem to me all the uses of this world,” I said, meaning it.

The next 26 lines took me deep down inside myself to a place I’d never been, where my inhibitions, doubts, and fears fell away. For one minute and fifty-five seconds, I melted into poetry that seemed to have been written for me centuries before I was born. “But break my heart,” I said at the end, fighting back tears, “for I must hold my tongue.”

Dazed, I walked to my desk and sat down. Emerging slowly from the mystical spell of Shakespeare’s lyrical iambic pentameter, I realized everyone had turned toward me, some with big smiles, others with tears in their eyes. They were clapping, and the applause went on and on.

Over the following weeks, I presented other scenes from Hamlet to good effect. For a dazzling few months I had visions of becoming the next Richard Burton, but I soon proved to be a one-trick pony, a reasonably good Hamlet, but mediocre to painfully awful in every other role, and my thespian aspirations met a swift, merciful death.

That performance stayed with me in a more important way, though. It became a small cornerstone of confidence, the first stone set in the construction of a long life.

I’d like to pretend here that I’m self-made, that hard work, sacrifice, and talent brought me to the good place where I find myself today, but looking back with a clear eye, I see a thousand turning points where flat-out pure luck played the decisive role and a thousand more where I couldn’t have gone forward without the help of someone who extended a hand to me gratuitously and unbidden.

A few years ago, a guy I hadn’t seen in fifty years tracked me down to thank me for talking him out of quitting our college fraternity when he was a pledge. He said I saved him from making a life-altering mistake. I appreciated his thanks, but wondered why he went to so much trouble. It was such a small thing that happened so long ago.

He died the following year, and I learned he’d been fighting cancer for a long time. I understood then. I was one of many on a long list.

Mrs. Halper, Mom, my aunt and uncle, Mr. Turner, and so many of those who helped me are gone now. I thanked some of them before they left. I wish I had a second chance with the others.

Many are still here. My list is long, too, but I’m fortunate. I have time.

Post Script: Suzie Glass and I were the last two kids standing in the seventh-grade spelling bee when the proctor called out the word “medieval.” It sat me down and Suzie won. To this day, that word aggravates me. Say it out loud, then explain to me why in hell it’s spelled like that.

August 12, 2021 @ 5:07 pm

Ken — we’ve not met but I was a member of your fraternity at UVA (’76). Don Smith sent me a link to this and I loved it…wonderful writing and an enviable ability to both recall and reflect on your earlier life. You have a gift…thanks for putting this out there and I hope to enjoy more of your work!

August 13, 2021 @ 8:36 am

Thanks, Mark, for reading my post and for your kind words! I was an undergrad 65 to 69 and graduated from the law school in 75, so we missed connecting back then by only a few years. Some of my older blog posts deal with my time at the house. If you’re interested, google The Blind Date and Ken Oder and you’ll find one about a road trip that changed my life. I can’t make the reunion if it occurs in November, but will probably attend if it’s in the spring. Hope to meet you then.

August 3, 2021 @ 9:29 pm

Ken, at 83, I catch myself that I do not take the time to thank many who have helped me along the way. Your story helped me to remember counselors who encouraged me to dream of going to UVA despite no family money for college, and helped me go to a DuPont scholarship meeting in Chatham that began my journey that continues today in Charlottesville. Ken , thanks for sharing your stories.

Fraternally Leroy

August 4, 2021 @ 7:46 am

Great to hear from you, Leroy. The English teacher I referred to in this post, Mr. Turner, played that role for me, along with a guidance counselor who helped me land a scholarship to UVA. Without them, I guess I’d be a retired ditch digger today. Lots of people to thank. Thanks for reading my blog and take care, Ken.

August 1, 2021 @ 12:35 pm

So eloquently written, Ken. Your real life experience stories are wonderful!

August 1, 2021 @ 4:52 pm

Thanks, Colleen!

July 31, 2021 @ 11:06 am

Your post touched my heart so much, Ken. Thank God for your mom, Mrs. Halper, your aunt and uncle + all the others along the way. What we do/do not do impacts others, whether we realize it or not.

July 31, 2021 @ 12:27 pm

Thanks, Marcy. Coming from the author who created Copper Daniels, who touched my heart so deeply, your comment means the world to me.

July 31, 2021 @ 6:53 am

Oh my!!! This post is one of the most touching that I have read. Perhaps it is because I have walked the day by day steps of your Mrs. Halper ! Or because I probably sat and listened to you as Hamlet!! Or because, I too, have had people who helped me through my journey of life!

YOU are one of those people! The connections through your blog and your writing have ignited another ember in my writing even at the age of 74!! I wish that my memory of details could even come close to yours!!! So many of my memories are fuzzy! I do remember how great Mr. Turner was as an inspiring teacher. And somewhere in the dark cave of my memories, I remember one day when our classmates piled Mr. Turners desk with FRUIT!! Thanks for your work and for your friendship through all of your sharing through written word.

July 31, 2021 @ 7:57 am

Thanks, Betty Lou. Teachers like Mrs. Halper and you changed the lives for the better of thousands of people like me. It must be so rewarding to know how much good you did for so many. I appreciate your kind words about the blog and how it has brought so many of us together. It’s one of the unexpected gifts that flowed from this late-life writing obsession. It gives us a reason and platform to share our thoughts and lives, even though, in my case at least, I haven’t seen you and the others in fifty plus years. I really appreciate your comments to my posts. They are always so insightful and make me think about the topic as much as writing the post did in the first place. Thanks so much for following my blog and for sharing your gems of reflection with me!

July 31, 2021 @ 5:18 am

One of your best posts yet. Thank you!

July 31, 2021 @ 7:50 am

Thanks, Don! The reunion you organized was the locus of the conversation with the brother I referred to near the end of this post. Can’t thank you enough for making that possible.

July 30, 2021 @ 11:24 pm

A few years ago I started writing notes to those women and men who had a profound impact on my life. But I often wonder if the the subtle nuanced prodding had more of a long-range impact.

July 31, 2021 @ 7:47 am

You are wise to see the need to thank without prodding. Most people, including me, aren’t so thoughtful. Writing this post made me realize the value of it. The startling realization for me, though, was the one you mention, the many, many subtle turning points that made all the difference. There are thousands of them.

July 30, 2021 @ 10:02 pm

Wonderful and heartfelt <3 Thank you Ken you are a great story teller I feel like I’m right there

July 31, 2021 @ 7:45 am

Thanks, Janet! This is another one that came from a place deep inside.

July 30, 2021 @ 2:57 pm

PS I still haven’t learned to Spell. I think 58 may be too late.

July 31, 2021 @ 7:44 am

I slaved over the spelling of the words in that post. If I’d made a spelling error in that one, I would never have lived it down. Even with spell check, you can screw up. Bobbye and I caught at the last minute that we’d typoed Norman Rockweel in the caption to the last photo. Sheesh!

July 30, 2021 @ 2:56 pm

As per normal Ken this is really great. I just so love you self-deprecating style and your humility. Such a great writer you are (that was Yoda speak). I think it really is a worthwhile exercise to look back on life turning points. I think it is also wonderful to then go back and let the people that had that kind of impact on your life, know about it, if they are still around. It is such a small thing but a great gift to those people.

July 31, 2021 @ 7:42 am

Thank you, Eric! One resolution that came out of writing this is I’m going to compose a heartfelt thanks to you and Pamela soon as Cindy’s second knee replacement surgery is behind us and and I can think straight again, hopefully. Talk about a turning point!

July 30, 2021 @ 1:36 pm

Beautiful post, Ken. Like you, I regret not thanking people, now long gone, for helping me through life. Thank you for the reminder to do it while I still can.

July 30, 2021 @ 2:08 pm

Thanks, Gay. What surprised me when I wrote this was the discovery and recognition of how many, many people helped me out. The list of those I still need to thank is indeed very long. I think this is probably true for most people. We just don’t realize it until we look back and remember all the turning points.

July 30, 2021 @ 1:33 pm

Ken. Your willingness to be vulnerable and share these stories is a gift to all of us who read your posts. This post took me back to the times I have stepped outside myself and accomplished something I didn’t think I could do. Kind of like my walkabout.

More importantly though, you remind us that those two word — thank you —mean so much. We get caught up in our own little wolds and forget to express our gratitude.

So I’ll start again now. Hey Ken, thank you for all you have done for me over the past 50 years. You helped me when I was at the bottom, and you’ve been a role model — albeit a tough one to follow!

July 30, 2021 @ 2:05 pm

Thanks, Lucian. It’s so true that we get caught up in our own concerns and forget to thank those that help us. You’re very good about remembering and expressing your appreciation. I’ve always admired and appreciated that trait in you, along with many others. You don’t need to thank me, though. Our relationship has produced reciprocal advantages for me. You were the one who talked Cindy into marrying me, right?

July 30, 2021 @ 1:02 pm

I can’t remember if you were policeman #1 or policeman #2!

July 30, 2021 @ 2:02 pm

I’m glad you don’t remember because I was comically terrible. I was the Sergeant. Jim White was the rebel. He was great in any role.

July 30, 2021 @ 11:38 am

L ove this. It brought back so many memories or senior English and Mr. Turner. I was not in your class but I am sorry I missed your presentation. Also I was that student who hid in the background but could memorize and present Shakespeare in front of the class without stumbling.

July 30, 2021 @ 2:00 pm

Thanks, Alice! We share those traits, it seems. Maybe there’s something about hiding in the background that causes us to do better when we’re required to step forward. I think that was true in my case.

July 30, 2021 @ 11:20 am

A great story Ken.You were so brave in front of the class.I never liked giving book reports in front of class.I do love books go figure!

July 30, 2021 @ 1:58 pm

Thanks, Larry. Reading books alone is a lot more fun than presenting to a class. A lot less stress and more interesting.