The Killer Storm

On August 20, 1969, Cindy and I awoke at 2 a.m. to a roaring, pounding din on the tin roof of our house in White Hall, Virginia. We jumped out of bed and ran to the window.

On August 20, 1969, Cindy and I awoke at 2 a.m. to a roaring, pounding din on the tin roof of our house in White Hall, Virginia. We jumped out of bed and ran to the window.

Lightning streaked across the sky. Thunder crashed. Through a silver sheet of water, we could barely see the big oak beside the house, its thick branches bowed downward, a lake swirling around the base of its trunk.

“Hardest rain I’ve ever seen,” Cindy said.

“Must be that hurricane they were talking about on the news,” I said.

“You think we’ll be okay?”

“We’ll be fine. It’s just a big storm. It’ll pass.”

I was right about the storm where we lived. Hurricane Camille blew through Albemarle County without causing much damage, but if we had lived in neighboring Nelson County, my confidence might have cost us our lives.

I was right about the storm where we lived. Hurricane Camille blew through Albemarle County without causing much damage, but if we had lived in neighboring Nelson County, my confidence might have cost us our lives.

At 2 a.m. when Cindy and I were staring out our bedroom window at the storm, John Fitzgerald rolled over in his sleep in Tyro, Virginia, just 30 miles south of us, and dropped his hand off the edge of his bed into cold water. Jarred awake, he bolted upright and peered into the darkness at the surreal scene of three feet of standing water in his bedroom.

His first thought was fear for the life of his infant son. When John and his wife, Frances, went to bed that night, they left their two-month-old baby in a bassinet in an adjoining room. John jumped up, sloshed into the other room, and switched on the light. In the midst of floating furniture, the bassinet bobbed gently like a little canoe on a rippling pond with the baby sleeping peacefully in its hull.

Frances splashed into the room. “Where’s the baby?” she screamed. John picked him up and handed him to her just as the electricity died and the light went out.

“Let’s get out of here,” Frances yelled.

John looked out the window. The Tye River, normally a hundred yards from their porch, had overflowed its banks and engulfed their home. Mud, rocks, and uprooted trees sped by the house on the back of raging floodwaters. “We can’t go out there,” he shouted.

Outside, the river would kill them. Inside the house, the water rose steadily. The attic was their only hope, John thought, but there was no access to it.

He waded back into the bedroom, retrieved a penknife from his pants pocket, climbed on top of a wardrobe, and cut a hole in the sheetrock ceiling. He helped Frances up into the attic, handed her the baby, and climbed up behind them. For the rest of the night, the Fitzgeralds rode out the flood astride the attic’s wooden rafters.

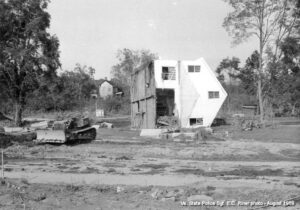

At dawn, the storm moved on and the river receded. John and Frances climbed down and went outside to find a landscape of death and destruction Camille had left in its wake. One corner of their house had been smashed away. A neighbor’s car had floated onto their porch and was wedged against the front door. The dead bodies of two women lay along the riverbank. A man’s cadaver was hung up in a fence below the house. A little girl’s hand reached skyward from a thick layer of mud caking the slope down to the Tye, the rest of her body buried beneath it.

At dawn, the storm moved on and the river receded. John and Frances climbed down and went outside to find a landscape of death and destruction Camille had left in its wake. One corner of their house had been smashed away. A neighbor’s car had floated onto their porch and was wedged against the front door. The dead bodies of two women lay along the riverbank. A man’s cadaver was hung up in a fence below the house. A little girl’s hand reached skyward from a thick layer of mud caking the slope down to the Tye, the rest of her body buried beneath it.

Like John, most of Camille’s Nelson County victims were caught unaware of its approach. Back then, there was no sophisticated storm-alert service to warn them about the storm’s magnitude or when it would arrive. It struck in the middle of the night while they slept, and with Nelson County’s steep mountainsides, narrow hollows, and deep ravines forming a perfect catch basin for the torrential rain, floodwaters swept many homes off their foundations before their residents could escape.

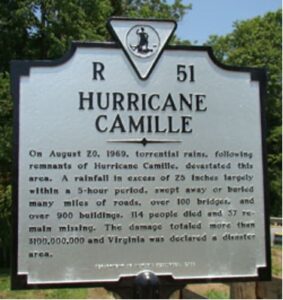

Camille’s deadliest aspect was the sheer volume of its rainfall, in some locations as much as 25 inches in 5 hours, which meteorologists computed to be the maximum amount of water the atmosphere could hold. Birds sitting in trees drowned. Creeks flash-flooded in mere minutes. Two thousand years of erosion took place in a single night, sweeping away miles of roads, 100 bridges, and 900 buildings. Property damage topped $100,000,000.

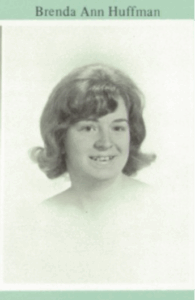

The toll in human lives was horrific. Camille killed 126 people in Nelson County; 184 statewide. Entire families perished. In Huffman Hollow, the flood wiped out whole branches of the Huffman family tree, killing 18 family members, ranging in age from 1 to 60.

I didn’t know anyone who died in the flood, but I had friends who lived through it, and they told me stories I’ll never forget.

One of my friends lived in a farmhouse perched on a hill overlooking a valley and a river. His family awoke that night to screams and ran out on their front porch. Through a gray torrent they saw the dim outline of houses floating on a churning lake that hadn’t been there when they went to bed.

One of my friends lived in a farmhouse perched on a hill overlooking a valley and a river. His family awoke that night to screams and ran out on their front porch. Through a gray torrent they saw the dim outline of houses floating on a churning lake that hadn’t been there when they went to bed.

People shouted from rooftops. “Help! Please help us!”

My friend ran down to the water’s edge. It was raining so hard he could barely see, and he had to cover his face to breathe. There was no way he could reach the people stranded on the water. He returned to the porch and stood there helplessly while his neighbors cried out to him.

There was an explosion. The lake whooshed away. A last burst of screams. Then silence.

There was an explosion. The lake whooshed away. A last burst of screams. Then silence.

Before the storm, a railroad overpass bridged the valley. The flood carried debris downstream that got hung up on the overpass’s struts, damming up the river and creating a huge reservoir. Upstream, the water rose so fast people’s houses were unmoored and afloat before they woke up. Clinging to rooftops, broken boards, and tree trunks, they rode the flood into the newly formed reservoir. It rose steadily until its weight broke the dam and tore down the overpass, crushing or drowning everyone trapped in the flush of water.

Camille hit Nelson County 56 years ago. My memories of it lay dormant until last fall when my brother-in-law made several trips from Charlottesville to Durham, North Carolina, to watch my granddaughter (his great niece) play soccer for Duke. He sent me a text message. “I drive by this sign a lot recently.” He attached a photograph of a Virginia historical road marker that commemorates Camille’s rampage through Nelson County.

Camille hit Nelson County 56 years ago. My memories of it lay dormant until last fall when my brother-in-law made several trips from Charlottesville to Durham, North Carolina, to watch my granddaughter (his great niece) play soccer for Duke. He sent me a text message. “I drive by this sign a lot recently.” He attached a photograph of a Virginia historical road marker that commemorates Camille’s rampage through Nelson County.

That marker brought back my memories of the storm, but it wasn’t the Fitzgerald family’s ordeal, Huffman Hollow, or the collapsed railroad bridge that first came to mind. It was a tangential personal connection.

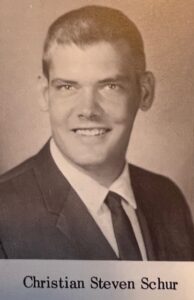

In 1965, when I was 18, my high school class went on a school trip to Washington, D.C. A classmate, Chris Schur, asked me to have lunch with him that day. I don’t know why he picked me. I barely knew him, and when we sat down at the lunch counter, he didn’t say much despite my attempts to draw him out.

In 1965, when I was 18, my high school class went on a school trip to Washington, D.C. A classmate, Chris Schur, asked me to have lunch with him that day. I don’t know why he picked me. I barely knew him, and when we sat down at the lunch counter, he didn’t say much despite my attempts to draw him out.

A few minutes into lunch, another classmate joined us, and he and I struck up a lively conversation. We tried to include Chris, but painfully shy, he could barely talk. His face reddened, and beads of sweat popped out on his forehead. After lunch, he wandered off by himself.

As far as I can recall, that was my last contact with Chris.

Four years later, a friend and I talked about the Nelson County flood. “You remember Chris Schur?” he said.

“Yeah. From high school.”

“His wife was killed in the flood.”

I didn’t know Chris’s wife and my only connection to him was that awkward lunch, but the news of his wife’s death hit me hard.

I didn’t know Chris’s wife and my only connection to him was that awkward lunch, but the news of his wife’s death hit me hard.

I searched for her obituary and found a brief entry in The Daily Progress. Mary Catherine Martin Schur died on August 20, 1969, of “multiple injuries and drowning.” She was a secretary for Vepco and a member of the Holy Comforter Church. Chris was an apprentice at a machine shop. They lived in Faber, Virginia. They’d been married eighteen months. Mary was 25 when she died. Chris was 24.

It took me a while to figure out why Mary’s death affected me so deeply. I remembered the introverted young man at the lunch counter, struggling to make conversation. I saw his tense face and those beads of sweat. Somehow, he had broken out of his shell and found someone to love, only to have her taken away from him. So tragic. So unfair.

I felt the need to reach out to Chris, but given that we barely knew each other, I could think of nothing that seemed appropriate. In the end, all I did was send flowers to the chapel holding Mary’s memorial service. “I am so sorry for your loss,” my note said. Hollow words from someone Chris probably didn’t remember.

Time passed. My concern for Chris faded away. Occasionally over the years, something would remind me of his loss, and the vague sense that I should have done more would nag at me, but for only a few moments.

Then came the Virginia road marker fifty-six years after the flood.

For reasons I don’t understand, this time thoughts about Chris wouldn’t go away. Wondering if he’d managed to put his life back together after Mary’s death, I searched for information on the internet. I couldn’t find much. Born in 1946, in Queens County, New York, Chris was a year older than my high school classmates, and he didn’t graduate with us. On my high school alumni website, he’s listed as a member of the class of 1966, so apparently, he was held back a year. An ancestry site indicates he never remarried after Mary’s death and he died in Palm Beach, Florida, in 2010 at age 64. That’s all I know.

For reasons I don’t understand, this time thoughts about Chris wouldn’t go away. Wondering if he’d managed to put his life back together after Mary’s death, I searched for information on the internet. I couldn’t find much. Born in 1946, in Queens County, New York, Chris was a year older than my high school classmates, and he didn’t graduate with us. On my high school alumni website, he’s listed as a member of the class of 1966, so apparently, he was held back a year. An ancestry site indicates he never remarried after Mary’s death and he died in Palm Beach, Florida, in 2010 at age 64. That’s all I know.

If any of my high school friends know anything more about Chris, I’d be interested in whatever you could tell me.

I’ve accumulated a few regrets over my long life. Most of them involve big screw-ups, but strangely, some of the small stuff that didn’t seem important when it went down still causes me minor discomfort, like little splinters under the skin of my thumb. They don’t hurt until I think about them, and even then, they don’t hurt much.

This little splinter won’t go away. I regret not reaching out to Chris. I wish I’d gone to his wife’s memorial service and spoken to him. I wish I’d been smart enough in 1969 to know that an expression of sympathy is never inappropriate in the face of overwhelming grief. I probably couldn’t have done anything for Chris, but I wish I’d tried. I just hope those close to him helped him find a path forward and his life turned out well.

This little splinter won’t go away. I regret not reaching out to Chris. I wish I’d gone to his wife’s memorial service and spoken to him. I wish I’d been smart enough in 1969 to know that an expression of sympathy is never inappropriate in the face of overwhelming grief. I probably couldn’t have done anything for Chris, but I wish I’d tried. I just hope those close to him helped him find a path forward and his life turned out well.

Post Script:

In Patrick Ryan’s novel, Buckeye, speaking about his state of mind in old age, Cal Jenkins says, “(Old people) aren’t living in the past; the past is living in us. And it’s talking. We get old to recalibrate everything we thought was going to be important. We get old just to hear it. It says, the days, the days, the days.”

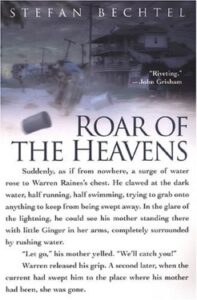

Stefan Bechtel’s Roar of the Heavens tells Camille’s many tragic stories. John Grisham, who now lives in Charlottesville, called the book riveting. I agree.

February 12, 2026 @ 3:39 am

Interesting that I gave the book Buckeye to my husband for Christmas since he is a Buckeye.. I remember Hurricane Camille. It was devastating. I met a little boy around 12 years old who lost his entire family — mother, father, siblings, aunts, uncles, and cousins. He had gone home with a school classmate to work on a school project. I don’t know what happened to him but when I met him, he was probably still in shock. My husband and I have experienced two hurricanes in the past few years — Hurricane Florence and Hurricane Helene. We had lots of propert damage from both, but thankfully, no physical issues. Thank you, Kenny, for reminding us of Chris. I, too, remember him as a quiet young man. You do have a wonderful gift with words. I love reading your stories. Thank you for sharing.

February 12, 2026 @ 8:07 am

Thanks, Veronica, for your kind words. “Buckeye” is a debut novel for its author, which is amazing to me because it is so strong, effective, and meaningful. A great story, artfully told. Your memory of the twelve-year-old boy is unfortunately not unique. My research for the blog led me to many stories of children who were orphaned or perished in that flood. It was a horrible tragedy. I’m glad you remember Chris. Many of our classmates seem to remember him, but no one yet has commented that they knew him well. And his his story after his wife’s death will remain a mystery to me, it seems. But everyone remembers him fondly, as a nice person, so hopefully he was able to persevere and recuperate from such a devastating loss. At least, that’s what I’m going to believe until something says otherwise. I’m glad you came through those two hurricanes well. I remember that one of them wreaked havoc and tragedy on North Carolina similar to the Camille disasters. I don’t miss the hurricanes since I left Virginia. Now, all I have to contend with are the mudslides, fires, and earthquakes. Sigh. Maybe not a good trade. Thanks, again for your comment and for following my blog.

February 11, 2026 @ 8:28 pm

Oh, Kenny once again your heart is on display. It just makes one feel so connected and so good to have a friend so talented that shares these wonderful stories that are from the heart. I loved what Cal Jenkins said about the past. It is true for me. The past does live in me and little unexpected things bring them out for me to remember. Sometimes with thinking back of “What if”. I guess most everyone has that at times. I know you made Chris happy that day just saying yes to sit with him and have lunch next to him. That meant more to him than you probably realize. I remember Chris just from saying hello in the halls. He had a nice smile and as you said was so painfully shy. I am happy he found love. Our daughter found it and lost it in about the same amount of time as Chris. Although she does not have a partner she has found love and friendships in other ways. I hope Chris found that too. It sounds like he was adventurous enough to make it to Florida. Sunshine is a mood booster so maybe over time he came out a little! Thanks for sharing that story of Chris. You mentioned a tin roof! I lived under a tin roof until I was 7 years old. At 79 can still hear the rains! You’ve heard-“I Got Married In A Fever”! Well‑I got moved in a Hurricane!!! In August of 1969 our dear family friend, Lacy Paulette and my Dad moved me in a pickup truck to Manassas, Virginia for my first teaching job!! I was so excited to have my own apartment! I was ready for an adventure and it really was one with torrential rains the entire way!! At times Lacy had problems seeing the road and we had to pull over. Can you believe it — but I cannot remember if most of my belongings were soaked!! The truck was full. We were blessed that the storm did not flood on our way. Thank you once again Kenny for a story from your heart and one that most of us in our age group from Charlottesville can remember. One thought before I leave—I know you are missing our classmate Mary. She enjoyed your work immensely and she enjoyed sharing it. I will miss her strong will and sense of humor with a twist. I know she was hoping to see you again one day but just know what joy you did bring to Mary and do bring to your high school classmates. Spring is on the was here in Virginia! A flock of Robbin’s visited today!! So—Happy Sunshine to you and your beautiful family. God Bless you always. Linda 🩶

February 12, 2026 @ 7:55 am

Thanks, Linda for your comment, heartfelt, inciteful, and moving, as always. You warm my heart. I’m sorry for your daughter’s loss. No one should have to endure a loss like that. I’m so glad she recovered from it so successfully, and I’m sure you played a big role in helping her through that. I hope Chris was able to rebound as well. Although I never got close to him, I always had the impression he was a good-hearted nice guy. I remember his “nice smile,” now that you’ve reminded me of it. Thank you for that. Your story about your move to Manassas during Camille is telling. It was a state-wide disaster. Nelson County took the biggest losses, I think because of its steep craggy terrain that made it vulnerable to the flooding, but my research for this blog educated me about losses throughout Virginia and the entire south from Mississippi on up. For the sake of brevity I didn’t include a heartbreaking story of the entire Clark family drowned in a flash flood in Rockbridge County, little kids and all, who were swept away before they could run from their house. There were so many tragedies. “Buckeye” is right that the past lives on in us in our old age. I don’t mind it talking to me. In fact, I’m glad it speaks to us, but I don’t like the other aspect of old age — the loss of our peers. Although I hadn’t seen Mary in 50 years (or any of you from the class of “65”) I grieve over her passing. We reconnected when she read my books and blog. She was so supportive and encouraging, writing positive reviews on-line and sending me messages with encouraging words. She even contacted my publisher and they became FB friends. I once joked with her that she was my east coast agent and that I’d cut her in on my royalties but I didn’t want to saddle her with a big pile of financial losses. I miss her so much. I’m glad spring is coming your way. We’re having good weather, too. It’s a much needed mood enhancer. Thanks so much again, Linda, for your beautiful comments and reflections.

February 3, 2026 @ 7:18 pm

You have left me speechless …You are such a gifted story teller and writer…deeply felt

thank you

February 4, 2026 @ 3:25 pm

Thanks, Janet!

February 1, 2026 @ 8:20 am

We have a second home in Nelson County and have seen that road sign commemorating the Hurricane many times. Thanks for bringing life and humanity to the story behind that marker.

February 2, 2026 @ 7:20 am

Thanks, Peter. I recall you published on FB some amazing photographic portraits of an old-timer at a country store in Nelson County that moved me. I started thinking about this blog back then. That road sign took me a step farther along. I admire and envy your immense talent with photography.

January 31, 2026 @ 5:23 am

Ken-

Thank you for this gift. I’m sitting here in a pool of tears and memories.

I’ve missed your posts. Please keep writing them!

Anchors up!

Lucian

January 31, 2026 @ 7:38 am

Well, I went through a three month dry spell there around the holidays. Things here overwhelmed me a bit, but then you sent me the photo of that road sign and it stirred up all those old memories. When I researched the flood, I stumbled across a couple of strange facts: Cindy and I were celebrating the two month anniversary of our marriage the night Camille hit Virginia, August 20, 1969; the Fitzgerald’s infant was born on Cindy’s birthday; and when I read Roar of the Heavens, details the author included about John Fitzgerald made me realize I had met him briefly at a country store his wife’s parents owned when Cindy and I drove around there one weekend a couple years after the flood. “The days, the days, the days.” The past talks to me, but it comes awake slowly and for unplanned reasons sometimes. Thanks for the inspiration. I needed it badly.

January 31, 2026 @ 12:34 pm

Lucian, I know you were the unnamed brother-in-law inspiration for this story. I was tapped into the Gravely/Fox hotline back in August.

Missed Camille, but lived through a few hurricanes including Edna in 1954 which took the chimney off our house in Plymouth, Mass., Donna in 1960 shortly after we moved to New Jersey. Was in Myrtle Beach, SC in 1989, but thankfully, we had mandatory evacuation just before Hugo.

Lesson: Don’t mess with Mother Nature.

Keep encouraging Ken. The stories are great even if sad sometimes.

Tom

January 31, 2026 @ 3:03 am

Wow, what a story, I moved to Virginia in 1972. I married Larry Deane and he told me all about the flood of 1969 and drove me down to the Nelson County area and showed me some of the differences in the landscape after the flood. He helped with some of the cleanup, he told me about the horrific sights.

It’s a heartbreaking story

January 31, 2026 @ 7:26 am

Thanks for your comment, Myrna, and for following my blog. The name Larry Deane rings a bell, but I can’t place him yet. Sometimes my memory of people from back in those days wakes up slowly. Maybe it will come to me. I left Virginia in 1975. I wish our paths had crossed before then, but at least you got the consolation prize of my brother, Larry, not a good as me but he ain’t bad. 🙂

My friends from Nelson County said after the flood that the county would never be the same. It was changed forever physically, and it changed forever the people who lived through it, too.

January 30, 2026 @ 8:36 pm

I remember Camille well. I was in the Air Force, stationed at Keesler AFB in biloxi Mississippi when Camille came on shore. The entire base was sheltered in the halls in cinder block barracks as the storm blew out windows and tore into homes and 100 year old oak trees. About a mile from the base an ocean going tanker found a new home 50 yards away from the gulf in a residential area. The highway that runs along the gulf was pieces of concrete and asphalt. The sound of the storm was like being between two freight trains, and it never seemed to want to stop. I think I learned about true fear in those hours of uncertainty and helplessness. A night that’s forever etched in my mind ……

I too remember Chris Schur, though I never knew him well — I’m not sure anyone did. Your words honor Chris, so thank you for that. As a hospice chaplain I see how much just a single word or hand on a shoulder can mean in times of grief. But also you remind us to reach out when you think of someone from your past and just say hello.

I so appreciate your heart felt writing and reflections on life Ken, and here’s my “hello” to you. Blessings to you and your family!!

January 31, 2026 @ 7:20 am

Thanks so much, Dan! The book about Camille Roar of the Heavens focuses in Part 1 on Camille moving up from Mississippi through the southeast, then sets forth the devastation in Nelson County beginning in Part 2, at page 116. I read Part 2 without looking at Part 1. Your story inspires me to go back and read that part as well. Thanks for sharing your personal experience from that night. It’s very moving and I can relate to it. I’ve had two near-death experiences. They concentrate the mind like nothing else and they truly teach you what fear really is.

No one so far has commented on knowing Chris much beyond the superficial level I reached. He was apparently the introverted guy I thought he was, and for me, this makes the death of his wife even more tragic. For that young man to have broken out of his shell to find love makes her death so much more tragic. And I wish I’d said that word of sympathy and put my hand on his shoulder, small gestures that wouldn’t have cost me anything and would probably have had the good effect you’ve seen in your hospice work.

I appreciate your thoughtful comments, Dan, and I admire your life’s work. Thanks for following my blog and sending me your thoughts. They mean a great deal to me.

January 30, 2026 @ 12:09 pm

I love your writing Ken. It’s straight from the heart and speaks to the time of life we’re in. I was reminded reading this that you and I are the same age, graduating high school 1965. Also it reminded me what a joy you were to work with in my long ago lawyer life. Sending love, Sonja

January 30, 2026 @ 1:16 pm

Thank you, Sonja. The projects we worked together were among my fondest memories of my time at Latham, and that was because of you. It bothers me to learn you and I are the same age, though. You look so much younger than me!

January 30, 2026 @ 10:51 am

Ken, I remember that storm! I was in Tallahassee, Florida. My parents lived in Covesville. They spent the night burning candles in the small upstairs bedroom in an old cabin that my father had renovated. The mountains just slid down toward the house and demolished the garage which held some wedding presents from our wedding. Mom wanted to leave… Dad said “No!” They made it safely through the storm with the only damage to their home being a couple of feet of mud in the downstairs. When my husband and I visited them (in an apartment in Charlottesville) for Thanksgiving… the area at the side of the house looked like an earthquake!

They built a house on the top of a small knoll closer to route 29. It still stands today! One of my fond memories of my parents’ scary experience was that when we went to church together on a later visit… I heard my father singing!! I had never heard him singing in church before

January 30, 2026 @ 11:29 am

Thanks for sharing that story about your parents, Betty Lou. I can relate to the decision to build on top of a hill after living through something like that. Every home we’ve owned has been out of the flood plane and away from the risk of mud slides. That storm lurked in the back of my mind each time we moved. Your father’s singing in church is an interesting outcome of the storm, tooe. That storm changed the lives of everyone who went through it. I’m just glad your parents were among the lucky ones. They survived.

January 30, 2026 @ 10:35 am

I remember the night the rain came. The next day at work I remember hearing about the flooding in Nelson County but had no idea of the magnitude until days later. I remember Chris Schur in high school. He was a nice guy but kind of reclusive. Every time I ride up 1–81 north of Raphine or through Nelson County I can still see evidence of the storm’s destruction where the trees and soil were washed off of the mountains.

January 30, 2026 @ 11:15 am

One of my friends from Nelson County said back then, “The storm changed everything. Nelson County will never be the same.” He was talking about the physical landscape, and he was right, but I think it also forever changed the lives of the people who went through it, emotionally and pschologically.

January 30, 2026 @ 10:19 am

Another provoker of thought. I have a few distant memories of people I forgot about but have sometimes wondered what happened to them. I learned about a few at my 50-year high school reunion. I’ve found some on Facebook. Perhaps I’ve forgotten more than I can remember.

January 30, 2026 @ 11:10 am

I’ve forgotten more than I can remember, too, but the memory of this guy stays with me, although I barely knew him. Sometimes I wish I had total recall Other times, I’m glad I don’t.