The Plumber

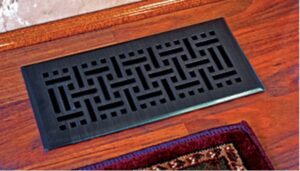

I army-crawled under the house and pointed my flashlight at the far corner. Through the haze of golden dust motes and silver spider webbing, I saw the aluminum duct lying on the ground. My goal was to reattach it to the bedroom floor-vent above it.

In my summer job as a plumber’s helper, I’d crawled under houses before. Musty, filthy, insect-infested, darker than a moonless night, it was never a pleasant experience, but the underside of this antebellum manse was the worst so far. Since its construction, the ground had shifted and the ancient floor joists had warped. In some places the clearance was less than six inches.

Slithering along on my belly, I came to a joist that blocked my path. I scooped out a trough in the dirt, rolled over on my back, and scuffed forward. I pushed my head through, but my chest wouldn’t clear. Squirming around, I got stuck so tightly I couldn’t move. Pinned like an insect on a poster board, I was fighting off claustrophobic panic when I heard a dry rustling sound to my left.

Alarmed, I cast my light in that direction. A black snake lay coiled an arm’s length away, staring at me, its eyes glowing like little diamonds, its tongue flicking in and out.

Alarmed, I cast my light in that direction. A black snake lay coiled an arm’s length away, staring at me, its eyes glowing like little diamonds, its tongue flicking in and out.

Merriam-Webster defines ophidiophobia as the “abnormal fear of snakes.” The genius who put the word “abnormal” in there obviously never squared off against a snake under a house.

I tore all the flesh off my chest lurching out from under that joist, set a land-speed record for a man crab-scuttling on his back, and flopped through the crawlspace opening into the twilight. After checking to make sure the black racer hadn’t followed me, I collapsed on the grass, my heart pounding as loud and fast as the kettledrums in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

This all went down at the tail end of a long hard day. Weeks earlier, the plumber, my boss, had landed a subcontract installing air conditioning systems in a housing development in Charlottesville. He trained me to run the ductwork and rough-in the vents, then hired Gilly Frazier and told me to teach him to do what I did.

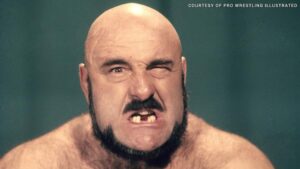

Among the hundreds of people I’ve worked with over my long life, Gilly ranked at the bottom in intelligence. Sixteen years old, five-five and 120 pounds with flaming red hair and a freckled face, he sported a cast on his forearm his first day on the job. When I asked about it, he said his daddy took him and his brother, Floyd, to a wrestling match in Charlottesville where some character named Mad Dog jumped off the ring’s turnbuckle onto an opponent lying flat

on the mat. Floyd came up with the bright idea of reenacting the match in their backyard, whereupon he jumped off a fence post onto Gilly’s forearm, snapping it like a brittle stick. “Floyd’s a dumbass,” Gilly said, doubling over in a fit of giggling, blissfully unaware that the bigger dumbass might be the brother who lay still while Floyd’s size twelves came crashing down on his arm.

Gilly said he dropped out of school because it was a “waste a time. Don’t larn nothin’. Cain’t figger what they’s talkin’ ‘bout.” He couldn’t figure what I was talking about either. He forgot everything I told him before I could finish telling him. With Gilly in tow, I had to work twice as hard to keep up with our production schedule.

Despite Gilly’s help, I’d finished installing an AC system by quitting time that day when the plumber got an emergency call to repair the AC in an invalid’s bedroom in the old manse, drove us there, diagnosed the problem, and sent me under the house while he and Gilly waited in the bedroom at the AC vent.

I was still stretched out on the grass trying to recuperate from acute ophidiophobia when the plumber and Gilly walked up on me. In his late forties, short and paunchy, the plumber was a good guy, but he operated on a tight budget and slow-downs on the job lit his short fuse. When he found me lying flat on my back in a catatonic stupor on his nickel, he exploded.

“What the hell are you doing?” he boomed.

I struggled to my feet. “I ran into a snake under there,” I said defensively.

“What happened to your chest?” he said.

I looked down to see crimson bloodstains on my t‑shirt and felt the sting of abrasions for the first time. I told him what happened. “There’s not enough clearance,” I said. “I couldn’t have made it to the duct even if the snake hadn’t showed up.”

The plumber’s temper usually cooled as quickly as it flared. This blast followed the pattern. “Sorry I yelled at you. We’ll put disinfectant on those cuts when we get home, but first we’ve got to find a way to fix the AC. Old man Woodson can’t breathe in this heat.”

The plumber knelt and flashed his light in the crawlspace. “The snake’s gone, but you’re right about the clearance. You can’t make it back to the corner.” He peered into the space for a while, then stood, and turned to Gilly. “It’s a tight fit, but you’re skinny enough to slip through.”

Gilly’s eyes widened. “It’s too dark,” he said.

“Take my light.”

Gilly swallowed hard. “I cain’t do it.”

“Don’t worry about the snake. He’s long gone. They’re more afraid of us than we are of them.”

“I ain’t scared a snakes.”

“Good. Then crawl under there and fix the duct so we can go home.”

His face twitching, Gilly backed away. “I don’t want to!”

The plumber’s tight-budget volcano erupted. “The hell with what you want! I pay you to do what I want! Get under there! Now!”

It was obvious where this was headed. In the month we’d worked together Gilly told me things he was ashamed to admit to most people. I knew why he couldn’t crawl under the house. I could tell the plumber and save Gilly’s job, but I’d carried him on my back like a dead body all day every day since he’d been hired. Stay out of it, I told myself.

I don’t think it was the tears sliding down Gilly’s freckled cheeks that got to me. More likely, it was the cumulative effect of a string of tell-tale signs: a purplish healed-over scar above his eye I’d noticed his first day of work, a discolored knot on his forehead that came and went a week later, red marks that encircled his throat shortly after that, and my growing doubts about his plaster-cast story.

“He’s afraid of the dark,” I said to the plumber.

“Who asked you to butt in?” the plumber shouted, turning on me.

“Gilly’s afraid of dark enclosed spaces,” I said evenly. “He has vivid nightmares about being locked in a closet all night long.”

A look of concern came across the plumber’s tense face.

“He dreams about that dark closet every night,” I said, giving the plumber a long, knowing look, hoping he’d pick up on my suspicion that Gilly’s nightmare wasn’t just a dream.

We both looked at Gilly. He kept his head down and said nothing. The plumber stared at him for a long time, then knelt down, and flashed his light under the house.

“The duct’s on the ground right below the vent,” he said. “The line’s joints held together.” He looked up at me. “You think we can reconnect it from the bedroom?”

I thought about it. “We should be able to reach it from above. If I can lift the line and nail the duct to the joists without the joints pulling apart, it’ll work.”

“Give it a try.”

It worked.

The next day, the plumber assigned Gilly to the senior man on the AC subcontract. A few days later, he told the plumber Gilly was untrainable.

I thought the plumber would fire him then, but instead he put him on a job running water lines and laying sewer pipe. Traditional plumbing is more straightforward than heating and air. Most of what you need to know springs off the trade’s three primary rules: “Hot on the left; cold on the right; and s*** don’t run uphill.” I hoped Gilly could catch on to it. When I left to return to UVA, he was hanging on to the job by his fingernails.

Three years later, I ran into him at Wyant’s Store in White Hall. He still worked for the plumber and was living on his own in Brown’s Cove. I didn’t see any fresh tell-tale signs.

As I watched Gilly’s beat-up pickup rattle off down the road to Crozet, I thought about the plumber paying him good money he couldn’t spare week after week, refusing to give up on him, stubbornly determined to unearth whatever talent lay buried deep down inside that sad kid.

It made no sense from a business standpoint, but like I said, the plumber was a good guy. Really good.

Post Script: The fear of snakes is among the most common of the 120 recognized phobias, afflicting 56 percent of adults, while Gilly’s fear of the dark, Nyctophobia, and its first cousin, Claustrophobia, each plague about 12 percent. Some extremely rare phobias must be difficult to cope with, like Baraphobia, the fear of gravity; Omphalophobia, belly buttons; Optophobia, opening your eyes; and my personal favorite, Hippopotomonstrosequipedaliophobia, the fear of long words.

December 15, 2021 @ 8:02 pm

Wow! Another wonderful story and so perfect for the Christmas season of giving. The Plumber, a kind and generous man in “his” way gave to Gilly a life long gift of confidence and a job! To you he gave the gift of sharing. He taught you the compassion in sharing and many useful skills. Your story was fun, interesting and exciting(especially when you and Mr. Snake were eye-ball to eye-ball! Your early jobs were so interesting and skill building. I had no idea as you sat in composition class that you were filled with these wonderful stories. Thanks so much for sharing your talent. Your ole’ highschool classmate, Linda

December 16, 2021 @ 12:04 pm

Thanks, Linda! Most people have experienced episodes in their lives that are remarkable and interesting. This blog gives me a reason to remember and write about mine. Thanks for following my blog. I appreciate your comments so much.

December 12, 2021 @ 8:04 pm

Enjoyed the story, Ken. Thanks. It was a very indirect Christmas message. Loved it.

December 13, 2021 @ 8:08 am

Thanks, Ursula. No one else seemed to notice the Christmas spirit in that story. Glad you caught it.

December 11, 2021 @ 2:42 pm

I loved The Plumber! I never would have gone under there in the first place!

December 11, 2021 @ 4:13 pm

Thanks, Kathleen. I haven’t been under a house since I quit that Job!

December 11, 2021 @ 2:39 pm

I had a snake in my garage over the summer and almost had a heart attack, so this is very relevant … As always, a fun recount of a story of life — loved it!

December 11, 2021 @ 4:12 pm

Thanks, Dan. My neighbor found a rattlesnake in his living room a few summers ago. Given a choice, I’d prefer the garage, I think.

December 11, 2021 @ 11:00 am

Great story. Have a great holiday. Tom

December 11, 2021 @ 4:11 pm

Thanks, Tom. Happy Holidays to you, too.

December 11, 2021 @ 7:52 am

Great story thank you for sharing as usual because of your amazing ability to tell a story visuals accompanied the words ??

December 11, 2021 @ 8:17 am

Thanks, Janet. Great to have you back.

December 11, 2021 @ 5:36 am

Another terrific story, Ken. Riveting in its narrative and heartfelt in your empathy for your coworker and your boss. I always enjoy reading your postings. Just finished your excellent book of short stories. What a gift you have. Merry Christmas to you and Cindy.

December 11, 2021 @ 8:17 am

Thanks, Dave. Great to hear from you again. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year to you, Tammy, and family!

December 10, 2021 @ 2:28 pm

By the third paragraph I was in full-blown heebeegeebee mode. Nice work, as usual, Ken!

December 10, 2021 @ 3:46 pm

Thanks, Eric. I still have nightmares about that snake. Happy Holidays!

December 10, 2021 @ 2:22 pm

Great story, Ken! Snakes and crawl spaces are two of my least favorite things. Heartwarming in the other respects! Keep ‘em coming and happy holidays.

December 10, 2021 @ 3:45 pm

I’m with you, Bob, on crawlspaces and snakes. Happy holidays to you and family!

December 10, 2021 @ 11:17 am

Gilly was lucky — he worked with two good men.

December 10, 2021 @ 12:44 pm

Thanks, Lucian.