First Cousins

Donald and I walked through Maupin’s apple orchard at noon on a hot sunny day in 1963.

Donald and I walked through Maupin’s apple orchard at noon on a hot sunny day in 1963.

“I can catch fish with my hands,” I said.

“No one can catch fish with his hands.”

“I can.”

“Bullcrap.”

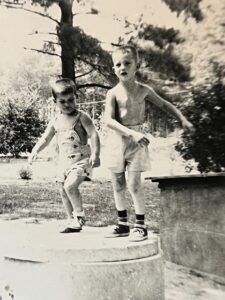

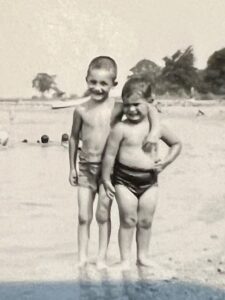

We were first cousins. Donald was 14, short with a spare tire of baby fat he would carry throughout his life. Skinny and a head taller than Donald, I was 16.

We climbed over the orchard fence, walked into the woods, and worked our way down a steep slope to Moorman’s River. At the Skunk Hole, a fishing spot named for an unfortunate incident involving our family dog, I took off my shirt, shoes, and socks and climbed up on a big rock.

“This is ridiculous,” Donald scoffed. “Quit fooling around.”

From five feet above the water, I cannon-balled into the deepest part of the Skunk Hole. The cold water braced me. I dove to the river’s floor, grabbed a big bottom-feeder, pushed upward, broke through the surface, and waved the wriggling fish above my head.

Donald’s eyes bugged out. “Holy Crap!!!”

Showing off, I let that fish go, caught another, released it, and caught a third.

My family had moved to White Hall, Virginia, a couple years earlier. Country boys had taught me a few tricks. One of them was hand-fishing.

My family had moved to White Hall, Virginia, a couple years earlier. Country boys had taught me a few tricks. One of them was hand-fishing.

Hand-fishing requires no skill. Mountain streams are bottomed with river rocks. The current washes away sand and silt, creating little open spaces between some of them. When you dive in, fish scurry to the little caves to hide from predators. If you place one hand over any exit hole and reach inside with the other, the fish has nowhere to go. You get a good grip and pull it out.

Donald was a city boy. My country-boy trick fooled him good. He stared at me worshipfully as we climbed the hill back to the parsonage. “I wouldn’t believe it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes.”

I strung him along for about an hour before I clued him in. He was a good sport, and we laughed about it.

I strung him along for about an hour before I clued him in. He was a good sport, and we laughed about it.

When we were little boys, Donald’s dad, my mom’s big brother, Keith, drove his family the 600 miles from Providence, Rhode Island, to Virginia’s tidewater area every summer to visit my family for a few days.

Our way of life must have shocked Donald at first. His family lived in a suburban neighborhood with city water, sewage systems, and paved streets. Their neighbors were office workers and shopkeepers. All the animals in his community were domesticated pets.

We lived on a sandy road in a clearing cut out of a pine forest. We drew our water from a hand-dug well and did our business in a wooden outhouse. Our neighbor was a guy who lived in a rusted-out school bus, its wheel hubs propped up on blocks in a soybean field. Deer raided our vegetable garden, and black snakes slithered through the grass in our backyard.

Despite our cultural differences and the short amount of time we spent together, Donald and I became great friends. We climbed trees, swam in the York and James Rivers, caught crabs in tidepools with hand nets, and, thanks to me, went nuts over baseball.

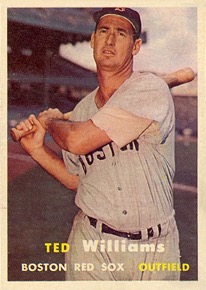

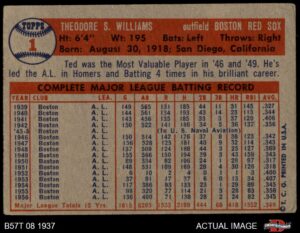

I was 8 years old when I got hooked on the Boston Red Sox. The Washington Senators were the closest team to my area, but they stank. Uncle Keith lived near Boston and was crazy about the Red Sox, so I adopted them as my team and Ted Williams as my favorite player.

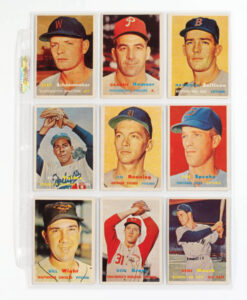

Mom bought me a couple packs of baseball cards shortly after that. This turned out to be a costly mistake on her part. Obsessed with trying to score a Ted Williams card, I forced her to spend $30,000 on 600,000 Topps 5‑cent-bubblegum packs over the next couple years. It was a hopeless quest. Topps printed almost no cards of good players so that kids would blow all their parents’ money chasing the superstars.

I’d rip open each pack excitedly only to be disappointed by yet another pile of .200 hitters and 10.00 ERA pitchers, never the good players, and never ever Ted Williams.

Then one hot summer day, Mom bought me five packs at a gas station in Lee Hall. Riding shotgun in our Hudson on the way home, I stuffed all the gum in my kisser and flipped through a stack of the usual worthless bums, but when I broke the seal on the last wrapper, I almost fainted. Mickey Mantle, Willy Mays, Hank Aaron, and TWO of TED WILLIAMS! The sadists at the Topps factory dumped all the future Hall-of-Famers into one blessed pack, and I hit the lottery!

I swallowed my bubblegum. The fist-sized wad got hung up behind my Adam’s apple. Strangling to death, I coughed and gagged while caressing the two Ted Williams cards to make sure they were real.

“You all right?” Mom asked.

Clutching my throat and heaving for air, I held my twin dream cards up to her and flashed a purple-faced smile. “Teh …Wims,” I croaked.

She frantically pulled off the road and pounded me on the back until I projectile-puked the deadly pink gob of gum onto the floorboard. When we got home, she went to the kitchen cabinet and downed a half-bottle of Dad’s nerve medicine. Oblivious to my near-death experience, I blissfully retreated to my bedroom to pore over Ted Williams’ career stats on the back of my thank-you-Jesus Teddy-Ballgame doubles.

Donald’s family came to visit the following week. When I laid out my Topps cards on the bedroom floor, it became clear Donald didn’t know anything about baseball. I spent all day teaching him about the game, the Red Sox, and the Splendid Splinter. I sank the hook deep. By the end of the day, he was a crazed addict.

The next morning, Uncle Keith took me aside. “You’ve accomplished a miracle,” he said, his voice quivering. “I’ve tried everything to get Donald interested in baseball. Nothing worked, but you’ve turned him into a Red Sox fan overnight. I don’t know how I can ever repay you.”

I knew exactly how he could repay me. “Take me to a Red Sox game,” I said.

The following summer Uncle Keith insisted my family drive to Providence for the annual visit instead of their coming to us. He sent me the Red Sox schedule and told me to pick a date. Figuring I’d never see another big-league baseball game during my childhood, I chose a doubleheader against the Washington Senators. “I understand the doubleheader,” Uncle Keith said, “but why the Senators? Don’t you want to see the Red Sox play a good team?”

“No! I want to see the Red Sox win.”

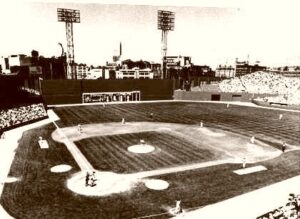

On a hot as hell day in July, Uncle Keith, my dad, Donald, and I took our seats on the ground level way down the third base line across from deep left field. In the first inning, when Ted Williams trotted out to stand in the shadow of the Green Monster, Fenway’s towering left-field wall, I was struck dumb. Donald could still talk, but barely. “Jesus,” he said softly.

If you weren’t a little kid whacked out of his mind about seeing your favorite team and player, that doubleheader was a miserable experience. There was no shade over our seats, and it was a muggy 95 degrees. At the end of the first game, which the Red Sox won, Dad wanted to go home. “We’ll get sunstroke,” he said.

“I don’t care,” I said. Donald backed me up. We stayed.

Halfway through the second game, the Red Sox pulled Ted Williams and subbed in Gene Stephens. Uncle Keith begged me and Donald to give it up. With my face broiled beet-red and my shirt drenched in sweat, I was on the verge of caving, but Donald said no. Uncle Keith got angry. He grabbed Donald’s arm and stood. “Come on. Let’s go.”

Eight-year-old Donald pulled his arm free and shook his finger at his dad. “This is Kenny’s big day!” he shouted. “We’re staying till it’s over!”

Uncle Keith looked at me for a long moment, then sat down. Dad almost cried.

In the top of the ninth inning, Jimmy Piersall climbed the center field wall to make the most spectacular catch I would ever witness, robbing Roy Sievers of a game-winning home run and securing my dream of the Red Sox winning both ends of the doubleheader.

When we got back to Donald’s house, I gave him one of my two Ted Williams cards. Overwhelmed with emotion, he hugged me.

My hand-fishing trick went down six years later in 1963. That trip to White Hall was the last time Donald’s family came to visit us, and it was the last time Donald and I got together.

We grew up, married, settled on opposite coasts, and raised our own families. We didn’t keep in touch.

When Uncle Keith died in 2004, I called Donald. A forty-year estrangement, a bigger wall than Fenway’s Green Monster, stood between us. We had changed too much, and the new guys didn’t know each other. Our conversation was short and awkward. We never spoke again.

Donald passed away in 2017.

Cindy and I have three children, two sons-in-law, a daughter-in-law, and eight grandchildren. Of that crew, about ten of us, including Cindy and me, have birthdays in June and July. This year we had one big birthday celebration last month for the Gemini/Cancer bunch, a cook-out and pool-party at our house.

That Sunday afternoon, I stood in the shallow end of our pool, watching four of our grandchildren taking turns cannon-balling off the jacuzzi wall into the deep end, about a five-foot jump. That long-ago day at the Skunk Hole came back to me. I thought about the Red Sox game and all the good times with Donald when we were kids.

Charlotte, River, Logan, and Wyatt are first cousins. They live close to each other and get together a lot. They have a special bond. It’s a great gift, I thought as I watched them. I hope they can keep it. I hope they don’t grow apart.

I got out of the pool and stood at the jacuzzi behind Wyatt. When he finished his dive, I stepped up on the wall.

A 77-year-old loon leaping off a high wall into a pool is a shocking spectacle, I guess.

Charlotte grabbed River. “Look! Papaw’s gonna jump!”

All eyes were on me.

I cannon-balled into the deep end. When I surfaced, Charlotte and the boys were laughing and cheering.

I climbed out, got in line behind them, and waited my turn.

I cannon-balled into the deep end three times. One for my grandkids. One for me. And one for Donald.

July 29, 2024 @ 1:39 pm

I loved your story because it reminded me of my MANY cousins on both sides of my family. The ones from the Charlottesville/ Earlysville areas always got together at reunions (Christmas, New Years, Mother’s Day, Thanksgiving). My cousins on my father’s side lived in Grundy. We traveled to visit there for our summer vacation. When others went to the beach… we drove to Grundy. We slept on feather beds, used outhouses and stayed in touch!

I loved the baseball part too! My grandson plays a lot and got to go to the State finals this year. They didn’t win, but it was great fun for our family to watch at Brownsville Elementary! Several weekends ago, Maddux taught me how to score in a real scorebook. We watched the Orioles and the Yankees play on television. He had taped the game. Watching that game together made me less nervous when I watch him play, because I realized that all the players have bad days. Keep your stories flowing!!!

July 30, 2024 @ 7:18 am

Thanks, Betty Lou. Other than Donald’s family, the families of my other cousins didn’t get together much. I had three cousins on my father’s side I only met twice growing up. One of them is now a Facebook friend and follows my blog. I wish we’d known each other when we were kids. I’m glad my grandchildren all live close to each other. They will likely be friends forever.

My son was a good ball player, like your grandson. His high school team competed for state championships and he played for Pepperdine in college. I went to a thousand games back then, I guess. It was hard to watch when he was in a slump, but luckily that wasn’t often. One of my riding pals is the mother of Christian Yelich, 32 years old, Milwaukee Brewer left fielder, National League MVP in 2018, 3 time All-Star and an All-Star first team selection this year. He’s a nice young man. His mom lives and dies with each of his at-bats. Makes me glad my son’s baseball days are behind him.

Anyway, thanks again for following my blog. Your comments are always insightful and help inspire me to keep writing.

July 27, 2024 @ 9:18 am

Pure gold, Ken. Reminded me of growing up in Southwestern Kentucky (Murray) and finding a Mickey Mantle card in one of my packs! Great stuff as always! Thanks.

July 27, 2024 @ 11:12 am

Thanks, Bob. Those Mantle cards were hard to come by. I got one in that same pack with the Ted Williams doubles. Never got another one. The Topps people were a devious lot.

July 26, 2024 @ 6:12 pm

For a couple of years his biggest competition for the BA title was a teammate Pete Runnels.

July 27, 2024 @ 7:05 am

You know, it’s a strange thing. There’s a hole in my memory about Runnels. I recall him as a Washington Senator, but until I researched this post, I didn’t realize he was traded to the Red Sox in 1958 and played so well for them. He won two batting titles and was inducted into the Red Sox Hall of Fame, but I blanked out on him. I could recite the Red Sox starting line up and pitching rotation for you up to the 1957 season, but my memory of them seems to blur after that.

July 26, 2024 @ 5:58 pm

I have no words 🙏♥️thank you

July 27, 2024 @ 6:58 am

Thanks, Janet.

July 26, 2024 @ 5:58 pm

The only major league game I have ever attended was a Red Socks game in 1969 while my ship was in the shipyard in Boston. Don’t remember who they were playing or the score, but Fenway was an experience.

July 27, 2024 @ 6:58 am

It’s a beautiful stadium steeped in magical history. My guess that I’d never go to another major league game during my childhood was correct. When clerking for a law firm in Atlanta when I was 24, the firm took me to a Braves game. When I moved to LA and my son came along I bought a share of Dodgers season tickets. He and I still go to a game every summer for Father’s Day, and I’ve been to a few Angel’s games over the years. I also attended abought 6000 college games when my son played left field for Pepperdine. So it’s been rags to riches for me on ball games, I guess.

July 26, 2024 @ 5:03 pm

Always glad to see you have posted a new story 😊

July 27, 2024 @ 6:51 am

Thanks, Sharon. I appreciate you following my blog.

July 26, 2024 @ 3:32 pm

Great story Ken. For me the baseball card treasure was Mantle, growing up just outside of NYC. You are so right about cousins. My wife and I both have cousin connections still, and we are enjoying our grandsons experience their cousins, (its an all boys club so far)

Best regards,

Bob Dunn

July 26, 2024 @ 3:59 pm

Great to hear from you, Bob. I got that one Mickey Mantle card, early in his career. Never got another one. Glad you stayed close to your cousins. Wish I had too.

July 26, 2024 @ 2:34 pm

Ken: Never knew you followed the Bosox. I have always been a Red Sox fan. Born and raised in Plymouth MA until I was 14. My dad took me to Fenway to see Williams play in his final season. I think the Sox lost, (they were pretty bad in 1960) but the trip was well worth it. Being Italian. I had lots of first cousins. I stayed in touch with some, missed some others.

Great story. Hope you are well. Tom Guidoboni

July 26, 2024 @ 3:16 pm

Thanks, Tom. I didn’t know you followed the Red Sox either. Williams was an amazing player. Batting average in the high 300’s into his last years in an era before steroids came along and extended careers. I used to check the major league leader batting average charts every morning in the newspaper to make sure he was still ahead of the young upstart, the dreaded Mickey Mantle. We are well. Hope you are, too.

July 26, 2024 @ 12:21 pm

I loved reading your post. Reminds me of all the summers spent with my cousins when we drove from Houston to Waterloo, Iowa. Fun times! We still keep in touch. When my brother and I drove up there in 2017, it was as if time hadn’t passed (except for the evidence of gray hair). Your post is a wonderful story as always!

July 26, 2024 @ 3:10 pm

Thanks, Rebecca. Glad you kept in touch with your cousins. Wish I’d done that with Donald. Cousins are special relationships.

July 26, 2024 @ 12:08 pm

I loved this story.

Two weeks ago I visited my brother in Kentucky. On the way home to North Carolina I came back via Virginia. I wanted some Virginia peaches and came through Crozet and White Hall. My cousin from Florida was with me and I wanted her to see where I grew up. We stopped at Wyant’s Store. David Wyatt came in and we chatted awhile. He remembered my family and spoke highly of my dad.. A warm feeling that he remembered my dad.

July 26, 2024 @ 3:09 pm

David was my high school classmate. I remember your dad, too. My dad also thought very highly of him. Everyone in the church did.

July 26, 2024 @ 11:41 am

Ken-

Again you brought me to tears of happiness. And that’s a pretty good cannonball for a 77 year old!

My dad went to his first Fenway game in 1946 — Game Five of the World Series against the Cardinals. You went to your first game there in 1957. Ten years later, the season of the Impossible Dream, my dad took me to Fenway for the first time and saw my hero Yaz hit an opposite-field home run into the net on top of the Green Monster. A couple of years ago, my son traveled from Atlanta to see his first Fenway Park game.

Even though I have never lived in Boston, Fenway has always been a very special place to me.

Thanks for inspiring me to think of those memories.

July 26, 2024 @ 11:56 am

Thanks, Lucian. I didn’t know your dad had gone to a Red Sox game, but it makes sense he would have. There’s something about the Red Sox and Fenway that captured the hearts of fans far away from Boston, at least in the old days. I loved that team in the 50’s. I got too busy after that and lost track. Sort of like with Donald.

July 26, 2024 @ 6:43 pm

Lucian — my grandmother was from Fall River and was buried with a Red Sox hat (this was before they won the 2005? World Series). There’s something about that team and 1940–2005. I went to a game at Fenway a few years ago with my dad and that is a memory I will cherish

July 27, 2024 @ 7:19 am

It’s amazing the number and diversity of Red Sox fans who seem to have no obvious connection to Boston or the team. Sorry your grandmother missed the Red Sox triumph in finally beating the curse. Thanks for following my blog.

July 26, 2024 @ 11:38 am

Love it Kenny, you’re the best

July 26, 2024 @ 11:52 am

Thanks so much, Buddy.

July 26, 2024 @ 10:49 am

A really cool story Ken. Reminds me of similar family trips and friend including those I have not heard from in probably 50 years or more. Thanks!

July 26, 2024 @ 11:52 am

Thanks, Randy. It’s hard to keep up the contacts when you’re busy, Bu I wish I had tried on this one.

July 26, 2024 @ 6:17 pm

Love your stories especially since they center around White Hall and Wyant’s Store. I only got to go to a Washington Senators game when I was in Little League. Met Jim Lemon after the game and got a baseball. Great memories.

I remember Bettie Head Hall being in the store several weeks ago and she got one of other shirts.

I’m keeping the light on for you!

July 27, 2024 @ 7:17 am

Great to hear from you, David! Bette logged a comment to this post about her visit to the store. She enjoyed her talk with you very much. My brother-in-law Lucian Fox also wrote me about visiting the store and talking to you. He bought me one of the T‑shirts and I wear it a lot. I’m also sitting here drinking morning coffee with the mug resting on a Wyant’s Store Home of the Liar’s Club coaster that Lucian sent me. I feature your store in my writing because it was the hub of White Hall social activity when I grew up. Still is, I guess. I have great memories of your grandfather Adam and your uncles Joe, Bob, and Billy. I can’t publish some of those, though. Ha ha. I’m really glad you and your brother kept the store going. It should be designated an official historical site.

I had forgotten about Jim Lemon. He was a good outfielder and I saw him play that day in 1957 in Fenway Park.

I really appreciate you following my blog and do keep the light on for me. I hope to get out there next year, and if I do, I hope to see you and the store again then.

July 26, 2024 @ 10:16 am

Great story Ken. Hope all is well.

July 26, 2024 @ 11:50 am

Thanks, Jim. We’re doing well. Hope all is well with you, too.