Margarine

I was riding Marge on the old Ahmanson Ranch on a cloudy morning in May when a swarm of bees attacked us. A few bees buzzed around me, but most of them went after Marge, swirling around her head, dive-bombing her face and neck. Shaking her head so violently it became a red blur, she backed up with short stomping steps and hopped sideways off the trail into tall grass.

The prospect of being thrown from a horse concentrates the mind, especially if you’re 77 with double knee replacements. Janet, my riding trainer, had schooled me well. I tightened my legs around Marge’s barrel, pressed my boots down firmly so I wouldn’t lose my stirrups, gave Marge more reins to shake off the bees, and focused on staying centered and balanced.

Desperately trying to free herself from the bees, Marge spun in a circle, stopped, jumped forward, backed up again, shook her head, and danced around frantically, but the bees stayed with her. Scared and stung, Marge began to buck, not big bucks, but a series of short little hip-hops.

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall.

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall.

But the big kicks never came. Instead, Marge lunged forward and broke into a full-on gallop across an open field.

Marge is an American Quarter Horse, a breed known for quarter-mile bursts of speed up to 45 mph. She can fly, and we did. I didn’t even try to rein her in. She was in runaway mode, and there was nothing I could have done to slow her down. I just held on as best I could.

About fifty yards into it, the wind from Marge’s bullet-speed peeled the bees away. They streamed by our sides like twin dark cirrus clouds. She ran until the bees were far behind us, then slowed down, and pulled up in a clearing near the ranch’s gate into Hidden Hills.

Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack.

Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack.

After Marge outran the bees, Janet and Jackson came up behind us at the gate. “Good riding,” Janet said.

“Thanks. You get stung?”

“No,” she said as she dismounted. “The bees went after you and Marge. Jackson and I got off easy.”

Marge was still greatly distressed, shaking her head and prancing nervously. I jumped off and held her head while Janet pulled two stingers from her neck. There had to be more, but we couldn’t find them.

Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.”

Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.”

I stayed with Marge at the barn longer than usual that day, petting her, hugging her, and giving her cookies and carrots. I didn’t leave until I was sure she’d calmed down.

That night as I lay in bed, I thought about the bee attack. Horses are prey animals. Their instinctive reaction to danger is to run. The flight reaction is imprinted in their genes, passed down over millennia through thousands of generations of wild horses. When the bees attacked, Marge carried 165 pounds of dead weight on her back. Scared and in pain, she should have thrown me so she could run away faster. It should have been an instinctive compulsion.

But she didn’t throw me. I thought about Marge for a long time that night.

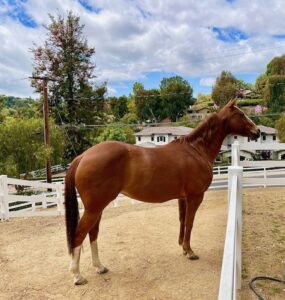

I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. (See For The Love of Horses.) Seven years ago, four months after my second knee replacement, I climbed on a horse while Janet held her in place. That horse was Marge, a sorrel (reddish brown) mare, small, 14 ½ hands (4 feet 2 inches tall at her withers), strong, with a wide chest and rounded, well-muscled hindquarters.

I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. (See For The Love of Horses.) Seven years ago, four months after my second knee replacement, I climbed on a horse while Janet held her in place. That horse was Marge, a sorrel (reddish brown) mare, small, 14 ½ hands (4 feet 2 inches tall at her withers), strong, with a wide chest and rounded, well-muscled hindquarters.

Janet purchased her from a barn in Stockton. She had a horse named Butter back then, so she named her new horse Margarine.

I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring.

I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring.

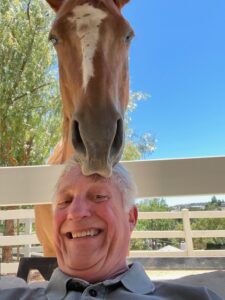

I have five horses now. I don’t play favorites, but if forced to choose one, I’d lean toward Marge. She’s mischievous, playful, and perky. She loves kids and dotes on my grandchildren, especially the little ones. And she loves Carrot Man.

She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair.

She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair.

She’s jealous when I pet another horse, kicking her stall door and pawing the ground until I give up and come back to her.

I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her.

I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her.

Don’t tell anyone this because it’s kind of embarrassing, but sometimes on solo rides I sing to her. “Margie, Margie, pumpkin pie/Kiss the boys and make em cry.” I think she likes it. I mean she pricks up her ears and all. That’s a sign she likes it, right?

Twice I thought I might lose Marge. The first time was a few months after I bought her from Janet. A horse has literally 100 feet of intestines. A lot can go wrong inside her belly. Kinks, blockages, and obstructions can cause colic, a painful and sometimes fatal condition. Marge got it bad. She laid down in her corral and wouldn’t get up.

The vet was tending to another emergency and couldn’t come till later in the day, so Janet took charge, keeping in touch with the vet by phone. We made Marge get up, walked her around, gave her a water-hose enema (believe me, you don’t want to know the details), and fed her soupy bran. By the end of the day, the logjam broke, and Marge recovered fully. We caught it early and she was probably never in serious jeopardy, but I was an equine neophyte at the time, and I was afraid she wouldn’t make it. Even that early in our relationship, she had a firm grip on my heart.

A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg.

A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg.

I knew more about horses by then. I knew that leg injuries are often fatal and that she probably wouldn’t survive a severed tendon or disabled fetlock joint.

With my heart in my throat, I texted a photo of the wound to the vet. He dropped everything and raced to my barn. Looking grim, he examined the wound and tested the fetlock. It only took a few minutes, but it seemed like hours to me.

“We can treat this,” he said, letting out a long breath. “She’ll be all right.”

I turned away from him and wiped my eyes.

As I lay in bed the night after the bee attack, I could still see the look in Marge’s eyes three years ago when she lifted her hoof to show me the wound to her leg. I saw pain and fear in her eyes, but there was something more, too. There was trust. She knew she was in trouble, and she was counting on me.

The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.”

The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.”

“I think you’re right,” I said. “It seemed like she did the best she could not to hurt me.”

“I know I’m right. Any other horse would have thrown you off.”

My bond with Marge did not come cheap. Tons of carrots and cookies, tens of thousands of pets and hugs, putting up with countless demanding bumps with her muzzle and buckets of horse spit on my shirt and in my hair, incessantly worrying about every hiccup that might signal another bout with colic, and opening her stall door every morning scared to death of what she might have done to herself this time. And there’s the singing. Don’t forget the singing.

It paid off, though. In pain and facing a threat she didn’t understand, Marge fought off the overwhelming equine instinct for self-preservation and sacrificed flight speed to carry me away from the danger.

“That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said.

“That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said.

This is true; it’s a great gift; and it goes both ways.

Post Script: Riding pal, Annabel, solved the mystery of Marge’s leg wound. She found dried blood on the wall below a piece of tin under a barn window in Marge’s stall. In an inexplicable acrobatic maneuver, Marge must have reared up against the window and slashed her leg on the tin’s sharp edge. It was a fluke accident, but I ripped out every piece of metal in my stalls.

Adrenaline and fear for your life are effective antidotes to bee venom, I guess. Although I felt no pain during the attack, I found sting-welts on my arms, neck, and back after I left Marge at the barn.

July 13, 2025 @ 4:56 am

We have 7 horses and it’s mostly a senior citizen’s home . We will love them all till the end . Thank you for sharing your stories.

July 13, 2025 @ 10:28 am

Seven! Wow! That’s great. They’re lucky steeds to have such a loving owner.

July 12, 2025 @ 8:01 pm

Marge sounds like a real sweetheart especially to go through a bee lashing like that for you! Never been around horses but your stories of Marge makes me think I should, not the riding just the kissing and hugging!

July 13, 2025 @ 10:23 am

Ha ha! Kissing and hugging is good, but the riding is fun, too, whenyou’re not attacked by a pack of bees.

July 12, 2025 @ 6:31 pm

Wonderful story, Ken. I’m glad you have Marge and that she has you.

July 13, 2025 @ 10:23 am

Thanks Bob.

July 11, 2025 @ 6:19 pm

Laughter and tears and an amazing beautiful recounting of that day and the following days of thoughts from the heart

The horses took good care of us

Thank you

July 11, 2025 @ 8:04 pm

You took good care of us, too, all the more remarkable because you’re allergic to bee venom, one of the many interesting details I had to leave out to keep the length of the article under control. It was twice as long in the first draft! Lot of excitement packed into those few minutes.

July 12, 2025 @ 10:00 pm

Absolutely, I was shocked that I didn’t get stung as that’s usually the case even when there’s just one bee !

I’m sorry you and Margerine got stung

Crazy experience we had and all in all we were lucky 🙏🏼🐴🐴

July 13, 2025 @ 10:26 am

We were very lucky. The techniques you taught me to stay on during a crisis helped an awful lot, too.

July 11, 2025 @ 5:44 pm

What an amazing story that shows how deeply horses bond with their humans. My Aria is a 32 year old Oldenburg mare and retired dressage horse. She was winning ribbons at 22. Still spry and youthful, she is my BFF and my heart horse. 🐎

July 11, 2025 @ 8:00 pm

Thanks, Michelle. Aria sounds wonderful! A BFF and heart horse is a great gift in life. Hoping you and Aria have many more years of partnership and love together.

July 11, 2025 @ 4:29 pm

I look forward to all of your anecdotes. This one is special!! Thanks Ken.

July 11, 2025 @ 7:56 pm

Thanks, Dan. I appreciate your encouragement.

July 11, 2025 @ 4:08 pm

Love this. It’s a wonderful thing that Marge loves you so.

I’m convinced that horses are huge dogs.

July 11, 2025 @ 7:55 pm

Thanks, Rebecca. Dogs and horses both have heart. Soul, too, although my preacher dad would probably have disagreed with me on that last part. Religious dogma says only humans have souls. But a heaven without dogs and horses doesn’t sound like much fun to me.

July 11, 2025 @ 2:40 pm

I love your stories about riding — especially Marge. I’m not a horse person but you tempt me. Keep sharing your stories! ❤️

July 11, 2025 @ 3:54 pm

Marge is calling your name! Come on out and give it a try. I’ll set you up with Janet so you’ll be safe.

July 11, 2025 @ 2:37 pm

Love a quarter horse! Great story about both of you.

July 11, 2025 @ 3:53 pm

Thanks, Cindy.

July 11, 2025 @ 1:26 pm

I love all of your stories! God bless you and Marge!

July 11, 2025 @ 1:44 pm

Thanks, Martha. God has been good to Marge and me!

July 11, 2025 @ 12:25 pm

Great photos.

July 11, 2025 @ 1:43 pm

Thanks, Mike. My brother-in-law took the best of these. We’ve got to set up that coffee.

July 11, 2025 @ 11:24 am

Ken, wonderful true story, thank you so much. I’m not into horses, but my niece my brother‘s daughter, that is all she does! She has a stable where she boards, horses and teaches riding lessons. I go out there once while just to look around and see what she is doing. Stay safe my big brother!

July 11, 2025 @ 11:32 am

Thanks, Blue. Sounds like your niece has got the same disease I came down with. If you’re into horses, it soon becomes all you do!

July 11, 2025 @ 10:50 am

Excellent story, as usual! Sadly, though, the friend I used to share your stories with passed away a month ago. Annie lost her battle with breast cancer, but she no doubt is still following you and your equine family from heaven!

July 11, 2025 @ 11:26 am

Great to hear from you, Don, although I’m so sorry about Annie. I’m glad she enjoyed the stories when she was with you and have faith she still follows them now. Gives me another reason to keep writing.

July 11, 2025 @ 10:40 am

Another great story Ken. Pets can get very much attached to their humans and these instances are good examples of such.

Keep the stories coming! I always enjoy reading them!

July 11, 2025 @ 11:22 am

Thanks, Randy. I appreciate your encouragement and your comments. Keeps me going.

July 11, 2025 @ 10:24 am

Ken Thank goodness you and Marge are safe from the bees. Yes you have a love and devotion to each other that when that happens it’s unique and special. I had that with my Coco. Marge will always do what she can to protect you and it’s beautiful to see this. Folks say animals don’t have love and care, they do and they show it in very special ways. But you also showed her several times you are there for her and she wants you to know it. Enjoy the nibbles and nudges as she is saying “Love you” to you..

July 11, 2025 @ 11:21 am

Thanks, Debbie. Marge’s affection is a great gift. Saved me from the bees! People who don’t understand the love and care of animals are missing one of the best parts of life.