Bone on Bone

The morning of my knee replacement surgery, my wife and I drove along Medical Center Drive at 5:30 a.m. When we turned into the West Hills Hospital parking lot, the headlights washed over a teenage boy wearing a pair of white boxer shorts, a blue bath towel tied around his neck, and nothing else, running along the sidewalk, laughing maniacally, tilting his outstretched arms back and forth like a big bird banking in the wind. We watched him sprint across the lot to the bus stop on Sherman Way, his shoulder length black hair and the towel fanning out behind him, his knees pumping, his bare feet slapping the asphalt.

The morning of my knee replacement surgery, my wife and I drove along Medical Center Drive at 5:30 a.m. When we turned into the West Hills Hospital parking lot, the headlights washed over a teenage boy wearing a pair of white boxer shorts, a blue bath towel tied around his neck, and nothing else, running along the sidewalk, laughing maniacally, tilting his outstretched arms back and forth like a big bird banking in the wind. We watched him sprint across the lot to the bus stop on Sherman Way, his shoulder length black hair and the towel fanning out behind him, his knees pumping, his bare feet slapping the asphalt.

“A bad omen,” I said.

“Means nothing,” my wife said. “If your surgeon shows up in his underwear, you’ll have something to worry about.”

Her comment conjured a nightmarish vision I could have done without. I let out a long breath and pulled into the lot. As I got out of the car, I watched a city bus slow down at the bus stop, then speed up, and pull away. Boxer-shorts boy waved his fists and screamed at it. I stared at him, hollow-eyed.

“Come on,” my wife said.

I trudged inside. The ancient volunteer lady at the reception desk gave us visitor badges. We took the elevator to the fifth floor and walked into the pre-op room.

The antiseptic smell of disinfectant. Blinding bright lights. Everything hospital white. Rows of beds along the windows. Computers and IV stands strewn around the room.

A stern heavyset nurse found me in her computer. “Right knee replacement. Full.” She launched into a detailed summary of the hospital’s plans for me that day.

I tuned her out. This wasn’t my first rodeo. My right knee was seventy years old, bone on bone, but my two month old left knee was made of titanium, and I knew what lay ahead for me. Empty of food from fasting but awash in nervous acid, my stomach rolled as I thought yet again that I could have avoided all this if I’d listened to my body.

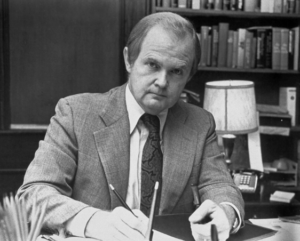

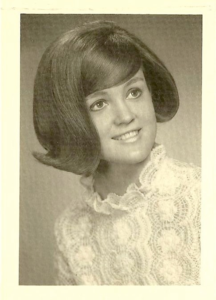

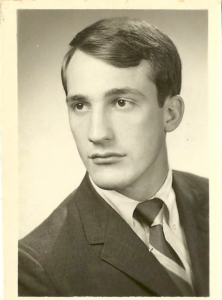

If you go by mileage, my knees lasted a long time. I started running to relieve stress in college. I kept it up through teaching, law school, practicing law, working as an executive, and retirement. I wasn’t fast, but I could run a long way at a slow pace, and I fell in love with it. In my forties, I ran in a few 5k and 10k races. I ran my first marathon when I was fifty-two. My goal was merely to finish. I barely made it, staggering across the finish line at five hours. Three days later, I started training for another one.

When I was sixty-two, I wrenched my back on a steep downhill slope at the end of a long run. The doctor found inflammation in my lower back and advanced arthritis in both knees. He told me to give up running.

When the swelling went down and the pain subsided, I hit the road again.

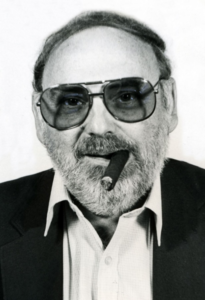

At sixty-five, my knees and back broke down completely. I tried everything to get back on the road. A doctor gave me a series of corticosteroid shots. A chiropractor adjusted my back, administered magnetic pulse treatments, jammed my legs in hip-boots inflated with air, and turned me upside down. I made bi-weekly visits to an acupuncturist. With Zen music playing in the background, I lay face-down on a gurney while he stuck needles in my lower back over my tail bone.

When I couldn’t walk fifty yards without pain, I came to grips with the truth: I would never run again, and I would have to go under the knife just to keep walking.

I went to a trainer to build strength in my legs before the knee operations. She started with a physical test. I couldn’t stand up straight; I leaned heavily to my right side when I walked; and I couldn’t step over a horizontal bar six inches off the ground.

Alone in the car on the drive home, I cried.

One month before my seventieth birthday, the surgeon replaced my left knee. When I woke up in the hospital bed, I expected a sharp pain, like a knife cutting into bone, but it wasn’t like that. It was a weary-to-the-core ache in my calf and thigh, so intense it felt like I’d run ten marathons back to back. The surgical team moves your knee-cap to the side when they install the new knee. This stretches all the muscles around the joint, and after they put the knee-cap back where it belongs, these muscles are rabidly pissed off and they do their best to make you scream, which I did.

The nurses’ protocol starts with a mild drug, like Tylenol, and progresses up a ladder of more powerful pain-killers until something works. My pain tolerance is apparently greatly wimpish. To peel me off the ceiling, they had to inject morphine straight into my IV. The next day they weaned me off morphine in favor of hydrocodone, and they sent me home with a bottle of pills.

The rehab went well. I walked without assistance on Day 4. Three weeks after the operation I got off the pain killers, and seven weeks later I was strong enough to undergo my second knee replacement.

Before the first operation, I was scared because I didn’t know what was going to happen. When they wheeled me into the operating room for the second one, I was scared because I knew exactly what was going to happen.

But boxer-shorts boy turned out to be a good omen instead of a bad one. The pain wasn’t as intense the second time around, and I walked without a cane on Day 4 again.

When the Medicare-covered rehab expired, I went back to the gym where my trainer had worked. She was no longer there, having moved north to attend graduate school. I didn’t think I could find anyone as good as she was, but she referred me to a young guy who panned out to be her equal.

My new knees healed quickly, and miraculously, a regimen he developed seemed to cure my back problems. I could stand up straight. I could walk long distances without pain. My balance improved. My strength came back.

At the end of workouts, my trainer sometimes put me on a treadmill, attaching weight by a strap around my waist, and I walked short distances, pulling the weight. We usually did six sets with breaks in between for me to catch my breath. The goal was to improve my time each session.

Four months after my second operation, I was walking on the treadmill. After the second set, my trainer said, “Try to pick up the pace this time. If you feel good enough, see if you can jog, but stop if it hurts.”

I looked at him fearfully. My surgeon said I could run short distances on soft surfaces, but I had been afraid to try. My trainer knew how much running had meant to me. “You can do it,” he said.

I started walking. A few steps into it, I broke into a ragged shuffle. My form smoothed out a little; I found a rough rhythm; and I ran.

When I finished, I looked over at him. He and two of the young trainers, who had watched my journey from the time I couldn’t step over a bar six inches off the ground on up to that moment, were clapping and grinning ear to ear.

I only covered sixty yards, pulling twenty pounds, and it took me almost thirty seconds, but I ran.

I ran.