Lily’s Room in the Cancer Hotel

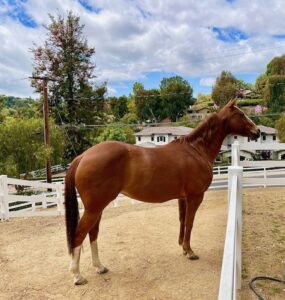

My trainer and good friend Janet called me one afternoon in July. “Marino says Lily is bleeding.” Her voice was tight, strained. “He says there’s a lot of blood.” Lily is a gray Azteca mare. Marino is the man who feeds my horses and mucks out the stalls.

My trainer and good friend Janet called me one afternoon in July. “Marino says Lily is bleeding.” Her voice was tight, strained. “He says there’s a lot of blood.” Lily is a gray Azteca mare. Marino is the man who feeds my horses and mucks out the stalls.

“I’ll go over there now,” I said.

“Call me when you get there. I’ll come in if it’s as bad as he says.”

When I arrived at the barn, Lily stood at her stall door. She looked alert, her ears pricked up, her eyes clear.

Inside her stall, I found blood smeared on the wall and crimson stains in the wood shavings of her bedding. Lily’s lush white tail was soaked red, and blood stained her back legs.

I lifted her tail. On its underside near the top, a black tumor the size of a crab-apple had burst and gushed blood.

I lifted her tail. On its underside near the top, a black tumor the size of a crab-apple had burst and gushed blood.

Looking at the blood in the stall and on Lily, I pieced together what happened. The huge tumor caused Lily discomfort. She backed up against the wall and rubbed the tumor against it, pushing so hard it ruptured.

Lily is 16. I bought her when she was 8. Her previous owner abused her. When we brought her home, she was afraid of men – me, the vet, Marino. Janet was able to work with her, but when I approached, she ran to the other side of her corral and stared at me fearfully.

I visited her every day, talked softly to her, and plied her with treats. About two weeks into it, she finally allowed me to touch her. See Lily’s Song for the full story.

Shortly after that, I found two small hard knots on her shoulder. Years earlier I’d seen growths like that on my dog. I knew what they were.

Shortly after that, I found two small hard knots on her shoulder. Years earlier I’d seen growths like that on my dog. I knew what they were.

I called the vet. In addition to the knots, he found a string of marble-sized black lumps on the underside of Lily’s tail. He confirmed my fears. “Lily has melanoma,” he said.

Equine melanoma is common among gray horses. About 80 percent of them become afflicted with it at some point in their lives. The cancerous tumors are usually located on the lips, around the eyes, along the neck, or on the underside of the tail. Over time, the tumors often multiply and grow larger.

There is no cure, but if the tumors don’t attack vital organs or impede bodily functions, a horse with melanoma may live to old age without significant adverse effects.

“Is there anything we can do to improve Lily’s chances?” I asked the vet.

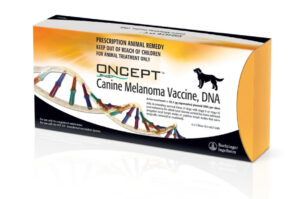

“There’s a vaccine for dogs,” he said. “Some dog vets will prescribe it off-label for horses. It doesn’t eliminate the tumors in horses, but it sometimes slows their growth. It’s expensive, and it often doesn’t work. Most owners let the cancer take its course and hope it doesn’t kill the horse.”

At my vet’s request, a dog vet prescribed the vaccine for Lily. We gave her shots every six months for the next six years. It seemed to work. The tumors didn’t grow much and remained confined to the underside of her tail.

Two years ago, production problems severely curtailed the supply of the drug. All off-label prescriptions for horses were terminated. The dog vet cut Lily off. We couldn’t get the drug anywhere.

Without the vaccine, Lily’s tumors grew rapidly, ballooning to the size of ping-pong balls, and spread over the entire underside of her tail in one conjoined mass.

In July, several large tumors erupted, oozing a brown pus that ran down Lily’s tail. The vet said there was nothing we could do other than clean her wounds, try to control the infections, and hope they heal.

They did not. Foul-smelling pus drained from them almost continuously. Wearing plastic gloves and facemasks, Janet and I washed and disinfected them every day. Then, the biggest tumor ruptured and bled.

She stood perfectly still at the wash rack while I bathed the bloody tumor in warm water. It stopped bleeding, and I coated the wound with an antiseptic cream. Although the sores on her tumors had to be painful to the touch, Lily hadn’t flinched through all our efforts to treat them, and she didn’t flinch that day. She seemed to know we were trying to help her.

In bed that night trying to find sleep, I couldn’t stop thinking about Lily. Life dealt her a cruel hand. Her previous owner’s abuse caused injuries to her shoulders and legs that never fully healed and contributed to the early onset of arthritis. Her gait is irregular, and she struggles on downhill grades. We give her medication daily to ease the pain.

In bed that night trying to find sleep, I couldn’t stop thinking about Lily. Life dealt her a cruel hand. Her previous owner’s abuse caused injuries to her shoulders and legs that never fully healed and contributed to the early onset of arthritis. Her gait is irregular, and she struggles on downhill grades. We give her medication daily to ease the pain.

Her psychological damage runs even deeper. We can’t erase entirely her memories of the abuse, but Janet and I have earned her trust. We groom her and pet her every day. I spend extra time with her whenever I can, stroking her gently and speaking to her softly. “Good girl. Pretty girl. I’m so proud of you.”

Perhaps because of her dark history, Lily responds to affection with more sensitivity and love than other horses. Janet says she’s the most soulful horse she’s ever worked with. I feel that, too.

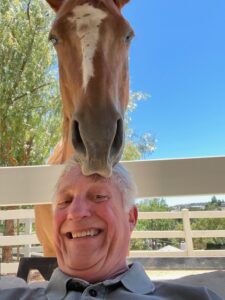

I felt it most last summer. The doctors found an extremely aggressive form of dermal melanoma in my shoulder beneath the skin. They were worried it had spread to other parts of my body. I was scared. I went to Lily’s stall the morning after my diagnosis. I stood beside her, my arm over her back, my forehead pressed against her neck. I don’t know if she understood, but it felt like she knew. I visited her several times during the tests and treatment. Although I don’t understand how or why, those visits gave me courage and hope. See The Cancer Club for that story.

As I lay awake the night after Lily’s tumor burst, I couldn’t shake the feeling I was letting her down. I was cancer-free, but she was still trapped in its constricting grip.

As I lay awake the night after Lily’s tumor burst, I couldn’t shake the feeling I was letting her down. I was cancer-free, but she was still trapped in its constricting grip.

In the morning, I called the vet and asked him to pull out all the stops to find the vaccine. I told him I didn’t care where he had to go or what he had to do. I’d pay to fly it in from anywhere in the world; I’d buy it on the black market; I’d do anything to get that drug. My emotions overwhelmed me, and I broke down.

The vet’s a good guy. He called the dog vet and begged her for the drug. Maybe he cried, too. I don’t know, but whatever he did, it worked.

The dog vet gave us the vaccine, and we resumed the shots in July. My vet also added an antibiotic to Lily’s daily feed, hoping it might heal the draining sores, and Janet tried a new disinfectant spray on the wounds.

The infections cleared. Lily’s condition stabilized. Her energy level returned to normal. Things looked good.

For a little while.

In August, Janet called me over to Lily’s stall. “Something’s wrong,” she said.

In August, Janet called me over to Lily’s stall. “Something’s wrong,” she said.

Lily loves carrots. Janet had given her one. It lay at her feet. She picked it up gingerly with her lips, dropped it, retrieved it, and dropped it again. She couldn’t chew it.

Most horses won’t let you probe inside their mouths and Lily is less trusting than others, but I was able to separate her lips long enough to glimpse a small black lump. My heart sank.

I called the vet. After giving her a tranquilizer, he examined her mouth. “She has tumors inside her jaws on both sides,” he said. “They’re small but there are a lot of them.”

This is the end of the line, I thought. The tumors only impeded her chewing of hard food so far, but I assumed it was just a matter of time until they metastasized and prevented her from eating anything. She would slowly starve, and I would have to confront a heartbreaking decision to end her suffering.

While I struggled to hold my emotions together, the vet continued to probe inside Lily’s mouth.

“Her lower molars are long and sharp,” he said, sounding excited. “Remind me, have we ever floated her teeth?”

“No.”

“How old is she?”

“16.”

We stared at each other hopefully.

As horses age, their molars grow and sometimes develop sharp points that make chewing uncomfortable. This usually occurs at about age 15. “Floating” is a dental procedure where the vet uses a power tool, a spinning wafer-sized rasp mounted on the end of a long metal column, to file down the sharp points. Lily was 16, and we had never floated her teeth.

The vet got his rasp, and I held Lily’s head while he floated her back molars.

When the tranquilizer wore off, Lily attacked a batch of carrots with her usual enthusiasm.

“It wasn’t the tumors,” the vet said. “It was her teeth. If we’re lucky and the vaccine works, the tumors in her mouth won’t grow large enough to become a problem.”

“It wasn’t the tumors,” the vet said. “It was her teeth. If we’re lucky and the vaccine works, the tumors in her mouth won’t grow large enough to become a problem.”

So, Lily lives on. But I’m a realist. Her room in the Cancer Hotel grows darker every day. We’re fighting hard – Lily, Janet, the vet, and I – but cancer is relentless. That dark day I dread so much still lurks out there somewhere.

Meanwhile, I’m trying hard to follow Janet’s advice to live in the present, like Lily does. Lily’s happy and content. She’s eating well and holding her weight. We pony her off Jackson, her favorite buddy, and lunge her in the corral. I groom her every day, stroke her neck and face gently, and speak softly to her. “Good girl. Pretty girl. I’m so proud of you.”

And I tell myself we still have time. We still have time.

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall.

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall. Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack.

Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack. Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.”

Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.” I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. (

I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. ( I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring.

I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring. She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair.

She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair. I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her.

I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her. A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg.

A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg. The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.”

The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.” “That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said.

“That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said. At 4:30 p.m. on November 12, 2004, a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) blew through a Black Hawk helicopter’s plexiglass chin bubble at the feet of its pilot, Captain Tammy Duckworth, and detonated in her lap, vaporizing her right leg, blowing her left leg up into the instrument panel, and shredding her right arm. The chopper went into a steep descent. Going in and out of consciousness, Duckworth grabbed the stick with her left hand and tried to guide the craft to a safe landing, but without legs she couldn’t press the floor-pedal controls.

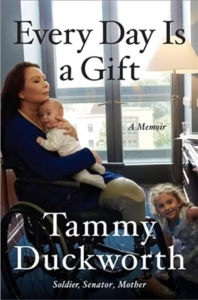

At 4:30 p.m. on November 12, 2004, a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) blew through a Black Hawk helicopter’s plexiglass chin bubble at the feet of its pilot, Captain Tammy Duckworth, and detonated in her lap, vaporizing her right leg, blowing her left leg up into the instrument panel, and shredding her right arm. The chopper went into a steep descent. Going in and out of consciousness, Duckworth grabbed the stick with her left hand and tried to guide the craft to a safe landing, but without legs she couldn’t press the floor-pedal controls.

I’m glad I was wrong about her injuries. In 2014 at age 46, she had a baby girl, and in 2018 at age 50, she became the first Senator to give birth while in office, another baby girl.

I’m glad I was wrong about her injuries. In 2014 at age 46, she had a baby girl, and in 2018 at age 50, she became the first Senator to give birth while in office, another baby girl.

I don’t write political posts, mainly because politics makes me sick (see

I don’t write political posts, mainly because politics makes me sick (see