The 1954 Hudson Hornet, Part Deux

I was tooling down Huntington Drive in my two-toned beige and brown 1954 Hudson Hornet when smoke billowed from the hood. I hit the brakes; the Hudson lurched violently to the right; the front tire rammed into the curb; and the engine stalled out.

I was tooling down Huntington Drive in my two-toned beige and brown 1954 Hudson Hornet when smoke billowed from the hood. I hit the brakes; the Hudson lurched violently to the right; the front tire rammed into the curb; and the engine stalled out.

I hopped out and slammed the door. The air was thick with the scent of burning rubber as steaming yellow-green coolant gushed from the Hudson’s front end and streamed along the curb to the gutter. I let out a long disgusted sigh.

By then the tow truck company occupied the top spot on my cell phone’s speed-dial directory. Connie, my frequent commiserator, picked up on the first ring. “That old crate’s costing you a fortune,” she said. “You oughta sell it.”

“No one in his right mind would buy it.”

“You did.”

“Proves my point. How long a wait this time?”

“Lester’ll be there in twenty.”

I pocketed my phone and leaned against the front fender, brooding yet again about the rash decision that got me into this mess. Years earlier, my brothers and I bought a broken-down 1954 Hudson Hornet for our dad. A Hudson dealer as a young man, Dad considered the Hornet the best car ever made. Restoring his Hudson became a labor of love for him and us. See The 1954 Hudson Hornet.

If the story had ended there, I would have lived happily ever after, but noooo. After we bought Dad’s car, my brother sent me the link to an ad on E‑Bay for the sale of a 1954 Hudson Hornet in Los Angeles. In the photograph it looked in near-mint condition. I made an offer conditioned on an inspection. My bid stood alone at the deadline, so the seller and I arranged to meet in a parking lot in Culver City.

Replacing a burned-out taillight taxes the limit of my automotive expertise, so I hired a young mechanic, Brad, to go with me. When we pulled into the lot, a hulking giant with a shaved head, sausage neck, and ugly scar slashing across his forehead stood beside the Hudson.

Brad looked under the hood while I tried to make conversation with the heavy. “You restore it yourself?” I asked.

“Man who fixed it up owes me money,” he said in a gravelly voice. “You buy it, he’s off the hook.” From his angry scowl I gathered he planned to break the man’s legs if I didn’t fork over the dough.

“Looks okay,” Brad said, “but we should test-drive her.”

“You can test-drive her all you want after you pay me,” Mr. Congeniality snarled, “and there won’t be no refund.”

Stupidly, I paid him.

The radiator boiled over twice on the way home. Brad found some pin-holes and soldered them. It overheated again, so he slathered sealant over the whole thing.

Then the brakes started pulling hard to the right. Brad fixed them. They did it again. He fixed them again. They did it again, and he fixed them a third time.

On the short drives to and from Brad’s shop, accessories spontaneously fell off. A door handle, the radio aerial, the Hudson emblem on the grill, the winged hood-ornament, the decorative chrome spaceship affixed to the trunk. These babies cost from 50 to 500 smackers each on the Hudson Club website, which was the only place you could buy them.

My repair costs exceeded the Hudson’s purchase price by the time the Hudson stalled out on Huntington Drive that morning when the freshly sealed radiator boiled over yet again and the thrice-fixed brakes jerked to the right.

While I was waiting for Lester and the tow truck, a shriveled-up ancient woman limped out of the Wells Fargo Bank and squinted at my car. “Is that a Hudson?”

“Yes, ma’am.”

She shuffled closer to it and peered in its rear window. “When I was a young girl, me and Bobby Dugan had us some fun in his daddy’s Hudson,” she said, giggling like a teenager.

This sort of thing is a common occurrence when you own a Hudson. Hudsons are chick magnets. Unfortunately, most of the chicks they attract don’t still have their own teeth. Judging by the wistful smiles of the sweet old ladies who admired my car, myriad romantic trysts involving couples born between World Wars I and II took place in a Hudson’s roomy back seat.

“I’d give you a ride in her, ma’am,” I said, “but she’s broke down.”

“Understandable. She’s nearly as old as I am.” She touched the front fender gently. “Thank you for the memories,” she said in a soft voice. Still smiling, Bobby Dugan’s long ago paramour turned and hobbled slowly down the sidewalk to Starbucks.

Lester towed the Hudson to Brad’s shop. He “fixed” the brakes again. Since he couldn’t find anything wrong with the radiator, we tried a different engine coolant. On the way home, the interior rear-view mirror fell from its mount and shattered on the floorboard. I drove to O’Reilly Auto Parts in San Gabriel to see if I could pick up a replacement on the cheap. The elderly clerk who waited on me was familiar with Hudsons. When I mentioned my recurring boiling-over adventures, he asked if he could take a look.

Lester towed the Hudson to Brad’s shop. He “fixed” the brakes again. Since he couldn’t find anything wrong with the radiator, we tried a different engine coolant. On the way home, the interior rear-view mirror fell from its mount and shattered on the floorboard. I drove to O’Reilly Auto Parts in San Gabriel to see if I could pick up a replacement on the cheap. The elderly clerk who waited on me was familiar with Hudsons. When I mentioned my recurring boiling-over adventures, he asked if he could take a look.

Out in the parking lot, he unscrewed the Hudson’s radiator cap and turned it over in his hand. “This is your problem,” he said. “Belongs on a Honda.” He rummaged around in the discontinued parts room and found a 1956 Oldsmobile cap. “It’s similar to a Hudson cap,” he said. “It oughta work.”

It worked. Cost me $2.56. Brad’s face turned fire-engine red when I told him.

After that, the Hudson ran great and nothing fell off. For about a week. We were chugging up Sierra Madre Boulevard when the engine sputtered. I headed for home in a panic. Missing badly when I pulled in the driveway, she conked out twenty feet from my garage.

Mad as hell, I stomped into the kitchen and unleashed a profanity-laced rant about my piece-of-crap Hudson.

“Maybe it’s out of gas,” Cindy said.

“It’s got plenty of gas!”

“How do you know? Thought you said the gas gauge was broken.”

“I put ten gallons in the damned thing two weeks ago!”

“It’s a big car. Maybe it guzzled it up.”

“Look, I know what I’m talking about! It’s not out of gas!”

“Okay, okay. I was just trying to help.”

Cindy’s suggestion was ridiculous! The Hudson had been sitting in the shop almost full time since I pumped in that ten gallons, for pity’s sake. Just to prove I was right, I filled a five-gallon can at the station, poured the fuel in the Hudson’s tank, got behind the wheel, and turned the key in the ignition.

It started right up.

I sat perfectly still for a good five minutes, staring blankly through the windshield, pondering betrayal, humiliation, and the futility of life in general.

“How’d you fix the Hudson?” Cindy asked when I slouched back into the kitchen.

“The solid lifters were stuck,” I said. “I greased up the cams and lugs.”

“That’s great! I didn’t realize you knew so much about cars.”

“Yeah, well …”

Taking care not to make eye contact, I retreated to my home office, cranked up the computer, and put the Hudson up for sale on E‑bay.

No bidders. I cut the price in half. Still no action. Two more cuts brought me down to rock-bottom, but even bottom-feeders wouldn’t take the bait.

I began to think the Hudson had become my Red Chief. In O. Henry’s short story, The Ransom of Red Chief, a couple of miscreants kidnap a boy to extort a ransom from his rich dad, but the kid is such a holy terror the dad is glad to be rid of him and won’t pay. When the kid pretends he’s the fierce Red Chief, ties one of the kidnappers to a stake, and sets his pants on fire, the bad guys end up paying the dad a healthy sum to take him back.

I began to think the Hudson had become my Red Chief. In O. Henry’s short story, The Ransom of Red Chief, a couple of miscreants kidnap a boy to extort a ransom from his rich dad, but the kid is such a holy terror the dad is glad to be rid of him and won’t pay. When the kid pretends he’s the fierce Red Chief, ties one of the kidnappers to a stake, and sets his pants on fire, the bad guys end up paying the dad a healthy sum to take him back.

I was on the verge of offering a cash reward to anyone willing to take the Hudson off my hands when a young couple fell in love with her. They were friends of ours so I almost warned them off.

Almost.

I mean, come on, that car was driving me nuts. Besides, the husband was a heavy equipment mechanic and had the skill to keep her running, and just in case he couldn’t keep her running, I gave them the Hudson for free.

So in the end this sad tale turned out well for everyone. The loan shark got his cash. The mark didn’t get his legs broke. Brad made a lot of money. The Hudson found a happy home. The young couple is still overjoyed with her.

And, most importantly, I’m overjoyed without her.

Post Script: Even smart successful people make tragic mistakes. Jay Leno’s collection of 169 cars includes a whole bunch of Hudsons. His net worth is estimated at $450,000,000. For now.

Mom woke me at dawn. I washed up, put on my new school clothes, and grabbed my Roy Rogers lunch box. She walked me down our dirt driveway and held my hand while we stood on the shoulder of Route 60, waiting for the school bus.

Mom woke me at dawn. I washed up, put on my new school clothes, and grabbed my Roy Rogers lunch box. She walked me down our dirt driveway and held my hand while we stood on the shoulder of Route 60, waiting for the school bus.

My stomach did a backflip.

My stomach did a backflip. Robert stopped crying when he saw me and clamped his sweaty hand onto mine. I tried to jerk free, but he held on like his life depended on it. He scooted his chair closer to mine and grabbed my arm with his other hand. I couldn’t make him let go, so we sat like that until the principal finally returned, disentangled me from Robert, and took me back to my class.

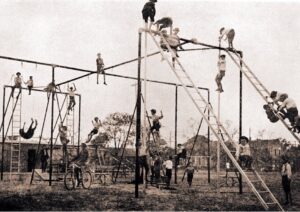

Robert stopped crying when he saw me and clamped his sweaty hand onto mine. I tried to jerk free, but he held on like his life depended on it. He scooted his chair closer to mine and grabbed my arm with his other hand. I couldn’t make him let go, so we sat like that until the principal finally returned, disentangled me from Robert, and took me back to my class. The first grade turned out to be fun for the most part – storytime, craft time, nap time. Recess was the best. They turned us loose on a playground that would qualify as a killing field under today’s safety standards. No plastic slides, rubber mats, or guardrails, and a fall from the giant iron jungle gym’s monkey bars held the promise of permanent paralysis, if not outright death.

The first grade turned out to be fun for the most part – storytime, craft time, nap time. Recess was the best. They turned us loose on a playground that would qualify as a killing field under today’s safety standards. No plastic slides, rubber mats, or guardrails, and a fall from the giant iron jungle gym’s monkey bars held the promise of permanent paralysis, if not outright death. He turned around and smiled at me with a wounded look in his eyes, sad and hurt, but mean at the same time. He reached over the seat, wrapped his hands around my throat, and began to choke me. I don’t know if the other kids didn’t notice or just didn’t care, but none of them did anything.

He turned around and smiled at me with a wounded look in his eyes, sad and hurt, but mean at the same time. He reached over the seat, wrapped his hands around my throat, and began to choke me. I don’t know if the other kids didn’t notice or just didn’t care, but none of them did anything.

Yeah. He almost crashed in the last race.”

Yeah. He almost crashed in the last race.” On a cold clear day in January 1987, Wendell Blake was picking up trash in Siever Manufacturing’s Los Angeles plant parking lot at 9:30 a.m. when he heard the grating sound of metal scraping against metal and looked up to see a tall man he recognized from company town-hall meetings, walking between cars four rows away, leaning toward the car on his right with his arm down at his side. The scraping sound stopped when the man came to the rear of the car. He walked on through the lot to a gray Mercedes, climbed in, and drove away.

On a cold clear day in January 1987, Wendell Blake was picking up trash in Siever Manufacturing’s Los Angeles plant parking lot at 9:30 a.m. when he heard the grating sound of metal scraping against metal and looked up to see a tall man he recognized from company town-hall meetings, walking between cars four rows away, leaning toward the car on his right with his arm down at his side. The scraping sound stopped when the man came to the rear of the car. He walked on through the lot to a gray Mercedes, climbed in, and drove away.

I questioned Blake in Siever’s conference room. A short stocky African American man, pushing forty, dressed in grease-smudged khaki work clothes, he answered my questions in a halting voice for an hour. I couldn’t shake his story.

I questioned Blake in Siever’s conference room. A short stocky African American man, pushing forty, dressed in grease-smudged khaki work clothes, he answered my questions in a halting voice for an hour. I couldn’t shake his story.