Bear and Roxy

I stood at the gate and pressed the buzzer. The speaker crackled, and the deep voice of the security guard responded. “Can I help you?”

“Mike. It’s me, Ken. Bear broke out again. I’ve got him down here with my dog.”

“Oh, Christ,” Mike said. “Be there in a minute.”

Bear was a Boxer. He was crazy about my American Bulldog, Zoey. Every time I took Zoey for a walk, he made a jail break to play with her, and I had to herd him back to his house.

Mike appeared at the top of the driveway in his black uniform, walked down the steps to the gate, and punched in the code. The gate hummed electronically and slid open. Built like a weightlifter, Mike grabbed Bear’s collar. “Don’t know how he got out this time. We fixed up all the holes he dug.”

“He jumped the fence at that low spot when we walked by,” I said, pointing down the hill.

“I’ll tell maintenance. Sorry for the trouble.”

“It’s no big deal.”

“Thanks again.” Mike dragged Bear up the hill. Roxy, his sister, waited for him, wagging her tail. She was timid and never tried to get out. They dashed through the port au cochere toward the back yard, and Zoey and I continued on our walk.

Cindy and I had moved to Hidden Hills to be closer to our grandchildren. Although we didn’t know it when we bought our house, a number of celebrities lived in the neighborhood, including Jennifer Lopez. She lived in a stately white brick house two doors down from us, and Bear and Roxy belonged to her.

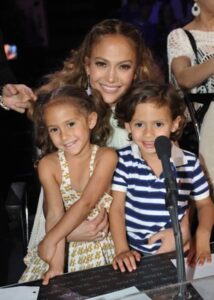

I’m not into the entertainment scene. When we moved here, I knew Jennifer Lopez was a big deal, but I couldn’t have picked her out of a line-up. One evening at twilight a year or two before Bear and Roxy showed up in her yard, I was walking Zoey around our block when I came up on a stunningly attractive woman pushing a double-seated stroller carrying a little boy and girl. “See the doggy,” she said to the toddlers. “Hi, Doggy,” she said a couple of times, smiling at me.

Zoey’s friendly, but her rough play with kids can cause problems. “Hi,” I grumped and moved on quickly.

When I told my daughter about the woman, she was flabbergasted. “That was J Lo, Dad, you idiot.” The tipoff, along with the stunningly attractive looks, was that J Lo had twin two-year-olds by some singer I’d never heard of who she’d recently divorced. Being clueless, I had dissed the mega-star.

I hoped I’d get a second chance, but no such luck. My encounter with her was an anomaly. Celebrities of her stature don’t normally venture outside their enclaves without an entourage. Several times I saw her Rolls Royce motor through her gate, but the back windows were tinted. All I could see was her chauffer in the front windshield, glaring at me like he hated me. In researching this post, I learned he and J Lo later had a falling out and she fired him. He sued her and she countersued him for blackmailing her, so maybe his dark scowl wasn’t about me.

After Bear and Roxy came along, my many trips to the security gate didn’t produce any contact with J Lo either, but one Sunday morning I managed to snare a consolation prize. Mike must have been off duty that day because no one responded to the buzzer at first. Then a young guy wearing swim trunks jogged through the port au cochere and shouted down to me, “Yeah, man? Whaddaya want?”

“Bear’s out again.”

“Oh, wow!”

High school age, short and muscular with a buzz cut, the kid ran down to the gate and pulled Bear inside. Bear wandered up the hill and began rooting around in the bushes. My gardener had found a huge rattlesnake in my front yard the previous day. Most houses in Hidden Hills have rattlesnake fences around the back yards, but the front yards are exposed because of the driveways. I warned the boy about the risk of a rattlesnake biting Bear.

“Oh, man, that sucks! What can we do about it?”

“Put him in the back inside your rattlesnake fence.”

“What’s a rattlesnake fence?”

It turned out J Lo didn’t have a snake fence, so I gave the boy the name of the contractor who installed mine.

“Wow, man! I’m gonna call that guy right now. We’ve got little kids in here. God, I mean, thanks so much, man!”

“That’s okay, man. Stay safe.”

When I asked my daughter if J Lo had a son in high school, she gave me the hairy eyeball. “What did he look like?”

I told her.

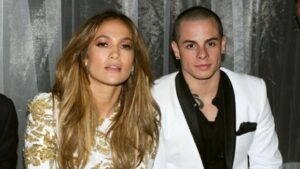

“That’s Casper, Dad, you idiot!”

This idiot thing was beginning to get on my nerves, but she had me dead to rights again. My age estimate was slightly off. Twenty-seven years old, Casper was the lead dancer in J Lo’s troupe and he was her main squeeze. On You-Tube, I watched her proclaim to some ditsy interviewer her undying love for Casper. She wanted to have his child, she said. On another tape, they did a sexy dance routine together. I was mystified. Casper was shorter than she was, fifteen years younger, and far from stunningly attractive. Certainly she could do better, I thought.

A few days later when I walked down to the mailbox, Casper jogged up the road at a good clip with Bear and Roxy in tow. Without breaking stride, he waved and flashed a big smile. “Hey, man!”

I waved back. “Hey!”

“Called that snake guy! Weird dude, but we bought the fence, man!”

“That’s great, man!”

“Thanks again, man!”

“No problem! Anytime, man!”

I watched him run over the hill. Well, at least he’s nice enough, I thought. And he seems to be in good physical condition.

A few days later the lady who lives next door appeared on our doorstep with a bandage on her hand the size of a watermelon. She said Bear had mauled her on her morning walk. She’d heard I had trouble with him and wanted to know what happened.

“He jumps the fence to play with my dog,” I said, “but he’s always been friendly.”

The next day I got a call from her lawyer. He’d filed a million dollar lawsuit against J Lo and wanted me to testify that Bear was aggressive. “He’s not aggressive,” I said. “He just likes my dog.” I argued with him for a while and then hung up.

A few hours later, Cindy answered the phone. A woman said she’d heard we’d complained about J Lo’s vicious dog.

“Who is this?” Cindy asked.

She said she was from Entertainment Tonight, the tabloid television show.

Cindy dropped the phone like it was a live rattlesnake.

The following week, Bear and Roxy disappeared from J Lo’s yard. My daughter told me she and Casper had broken up. On the internet, I learned Casper got custody of the dogs.

A month later, the lady next door told me J Lo paid her a large damage award to settle her lawsuit.

Shortly after that, a fleet of moving vans pulled up to the security gate; an army of movers loaded up enough furniture to decorate the governor’s mansion; and the trucks convoyed out of Hidden Hills.

An osteopathic surgeon bought J Lo’s house and moved his family in. Nice people. Kind of boring, though. Like us.

That all went down a couple of years ago. J Lo has moved on with her life since then, hooking up with Alex Rodriguez, so it’s clear she’s gone for good.

I’m still bummed out about it. I miss all the excitement. J Lo, the twins, Mike, the Rolls Royce, Bear, Roxy, all gone from my life, and it’s really hard to accept that I’ll never see my good buddy, Casper, again.

I’m still bummed out about it. I miss all the excitement. J Lo, the twins, Mike, the Rolls Royce, Bear, Roxy, all gone from my life, and it’s really hard to accept that I’ll never see my good buddy, Casper, again.

Worst of all, I didn’t even have a chance to say, “Goodbye, man!”

Working shoulder to shoulder with Jack wasn’t exactly a barrel of laughs. Taciturn and quiet, he didn’t seem to have much of a life. He lived alone, could barely read or write, didn’t have any interests outside his job at the Co-op, and didn’t have any friends other than Mrs. Pugh, whose kind, fair treatment had earned his devotion. My attempts to cheer him up only rarely broke through his stiff-jawed frown to produce his version of a smile, a short-lived uptick at the corners of his mouth and a single quiver of the ubiquitous Camel.

Working shoulder to shoulder with Jack wasn’t exactly a barrel of laughs. Taciturn and quiet, he didn’t seem to have much of a life. He lived alone, could barely read or write, didn’t have any interests outside his job at the Co-op, and didn’t have any friends other than Mrs. Pugh, whose kind, fair treatment had earned his devotion. My attempts to cheer him up only rarely broke through his stiff-jawed frown to produce his version of a smile, a short-lived uptick at the corners of his mouth and a single quiver of the ubiquitous Camel. I was happy for him. Then I met Becky.

I was happy for him. Then I met Becky.