The Thin Blue Line

Riots erupted in South Central Los Angeles Wednesday afternoon, April 29, 1992, when a jury found four LAPD officers not guilty of assaulting Rodney King. Violence ruled the night and continued into Thursday morning when I arrived at my office at Latham & Watkins on the 43rdfloor of a downtown skyscraper. My office window offered an unobstructed view of LA’s south side. I counted seventeen spires of smoke curling into the sky from burning buildings. The conflict was five miles away, so I thought it posed no risk to our location. I was wrong.

The event that led to the riots occurred a year earlier, on the night of March 3, 1991. California Highway Patrol officers attempted to stop Rodney King for speeding. He tried to outrun them. The CHP gave chase and LAPD patrol cars joined the pursuit.

Most of the officers were white. King was black.

The Holliday Videotape

The police forced King off the road in the Lake View Terrace district. He resisted arrest. The LAPD officers tasered him and knocked him to the ground.

At that point a local resident, George Holliday, began filming the action with a Sony Handycam from his apartment balcony. The tape begins with King on the ground. He gets up and tries to run. The officers knock him down, circle him, and club him with batons, landing 40 to 50 hard blows.

Holliday sent the tape to a television station. Media outlets all over the world picked it up and played it repeatedly. Photos of King’s injuries also went viral.

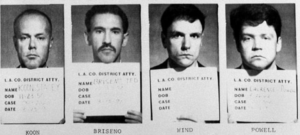

Booking Photos: Sgt Stacey Koon,

Theodore Briseno, Timothy Wind, Laurence Powell

The district attorney charged four LAPD officers with assault and use of excessive force. In response to a change of venue motion, the court moved the case to Simi Valley. The jury pool in LA would have included a large minority population. Simi Valley was a predominantly white community.

The trial began in March, 1992, with a jury of nine whites and three minorities, no blacks. The prosecution relied heavily on the tape. Surprisingly, the defense relied on it, too, playing it in slow motion, frame-by frame, as an expert witness testified that King’s movements justified each baton blow.

Court TV broadcast the trial live.

Racial tension in LA was at the breaking point when the court announced the not guilty verdicts on Wednesday, April 29, at 3:15 p.m.

Rioters at the intersection of Florence and Normandie

One of my friends at Latham was trying a case in Inglewood that afternoon. Worried about a violent reaction to the King verdict, the judge in his case adjourned the proceedings early. On my friend’s way to the freeway, he drove through the intersection of Florence and Normandie in South Central about 4:30 p.m. He may have been one of the last motorists to pass through unharmed.

A few minutes later, LAPD officers attempted to arrest a man who had thrown rocks at their car near there. They were quickly surrounded by an angry crowd. Other officers arrived at the scene. The crowd threw rocks and bottles at them and they retreated to a bus station twenty blocks away.

Unchecked and Out of Control

Several men then robbed Tom’s Liquor Store at that intersection, shouting, “This is for Rodney King.” They passed out liquor bottles to others on the street, and they began pulling people out of cars and beating them.

News helicopters flew to the intersection and filmed the mayhem. Of the many violent incidents, the most graphic was a live broadcast of rioters dragging a truck driver, Reginald Denny, from his rig, knocking him to the ground, stomping him, beating him with a claw hammer, and smashing his head in with a concrete block.

Some of Latham’s staff members lived in South Central. They were afraid to go home Wednesday evening, so we set them up to spend the night in the offices.

The riots continued through the night. The violence remained focused in South Central, so most everyone at Latham came to work Thursday morning, worried but not yet alarmed about our personal safety.

South Central LA Burning

By mid-morning I was alarmed. The smoke plumes outside my window had multiplied, and they were creeping toward downtown.

Latham employed more than 200 attorneys and hundreds of staff employees in LA. I was the Managing Partner of that office. It was my responsibility to decide whether to shut down and send everyone home. I hesitated, worried about turning off the billable-hours spigot on 200 big-time attorneys when I didn’t know for sure the riots would reach our building, but when the fires came within a mile of us, I pulled the trigger and announced a closure.

The staff bolted for the doors. Most of the attorneys packed up and got out, too, but some of them wanted to stay and work. I went door to door, urging them to leave, citing Reginald Denny as Exhibit A. Everyone eventually vacated the office.

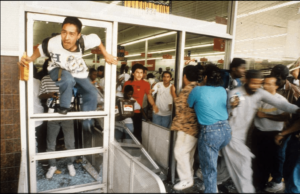

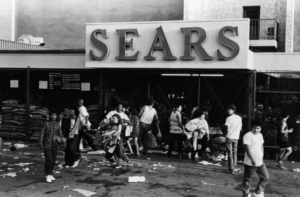

Looting

When I drove out of downtown at 2:00 p.m., the streets were clear. Two hours later, the rioters overran our location. I sent a message to all LA personnel closing the office Friday and through the weekend.

That night, the riots spread to Hollywood and the west side. Friday, the violence remained unchecked and out of control.

I was scared. In most of the televised coverage, the police were nowhere to be seen. I didn’t know how to protect my family.

A Latham attorney, who lived in my neighborhood, drove his family 50 miles north and checked into a motel. My wife and I didn’t want to abandon our home unless we had no other choice. They’re attacking businesses, not residences, I told myself. At least so far.

Fighting Back From the Rooftops

In Korea Town, news cameras filmed shop owners taking matters into their own hands, standing on rooftops with rifles, firing down on the street. From my hunting days in Virginia, I had a shotgun and a rifle in the attic. I cleaned them up, propped them by the front door, then sat on the steps staring at them, wondering if I’d gone as crazy as the rioters.

Marines moving up I‑5 to LA

The LAPD tried to regain control Friday, making over a thousand arrests, but the riots raged on without skipping a beat.

Governor Wilson sent in the National Guard and President Bush deployed Marines. Combat troops in military vehicles rolled down the street a half-block from our house.

The soldiers restored order and brought the riots to a close on Monday.

The cost was staggering: 63 people dead, 2383 injured, over one billion dollars in property damage.

Legions of commissions and analysts have studied the riots since 1992, but the causes were clear from the outset. Too many LAPD officers used excessive force with impunity back then. The billy-clubbing of Rodney King was a product of that culture. It went beyond the point of overkill. The jury verdict denied the undeniable and lit a powder keg of pent-up anger fomented by decades of racism and relentless poverty in South Central.

The Emblem of the Thin Blue Line

A cold hollow place opened in the pit of my stomach as I wrote this post. It took me back to that helpless feeling of 25 years ago. I’d heard of the thin blue line before 1992, but the riots taught me what it means. The barrier between anarchy and civilized society is thin. Law enforcement guards that line. Without the police, order breaks down and all hell breaks loose. You can try to run from the chaos or you can try to fight it from the rooftops with rifles, but nothing really works.

Bad cops must be removed, but the good ones, who are the vast majority, deserve our respect and support. Without them, no one is safe.

Post Script: LA paid Rodney King 3.8 million dollars in damages. Having struggled with drug and alcohol addiction all his life, he drowned in his swimming pool while intoxicated in 2012. He was 47.

Reginald Denny’s skull was fractured in 91 places. He didn’t receive a dime for his injuries. The men who attacked him didn’t have any money and he lost a lawsuit against LA. Despite years of therapy, at the age of 63 his speech and motor skills remain impaired.

The U.S. Justice Department prosecuted LAPD Officers Stacey Koon and Laurence Powell for violating King’s civil rights. They were convicted in 1993 and sentenced to 30 months in prison.

In 1987, my son played baseball in Beijing. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invited the U.S. to field Little League teams to compete with Chinese kids. Two coaches put together a team from California. My son made the roster, and I volunteered to go along as a parent-chaperone.

In 1987, my son played baseball in Beijing. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invited the U.S. to field Little League teams to compete with Chinese kids. Two coaches put together a team from California. My son made the roster, and I volunteered to go along as a parent-chaperone.