Hitting The Wall

A gray mist shrouded a sea of bobbing heads crawling past the Mile 23 sign. A sinewy ancient man wearing plaid Bermuda shorts, black nylon socks, and orange tennis shoes clumped along beside me. His iron-gray hair cinched in a ponytail, his leather face lined with a thousand creases, his every breath whistling like a tea kettle, he rasped in a singsong, sandpaper voice, “Run for the money, wheeze-wheeze, run for the gold, wheeze-wheeze, run till you’re o–o–o–old, wheeze-wheeze.” He flashed a taunting grin at me, picked up his pace, and disappeared into the crowd up ahead.

A gray mist shrouded a sea of bobbing heads crawling past the Mile 23 sign. A sinewy ancient man wearing plaid Bermuda shorts, black nylon socks, and orange tennis shoes clumped along beside me. His iron-gray hair cinched in a ponytail, his leather face lined with a thousand creases, his every breath whistling like a tea kettle, he rasped in a singsong, sandpaper voice, “Run for the money, wheeze-wheeze, run for the gold, wheeze-wheeze, run till you’re o–o–o–old, wheeze-wheeze.” He flashed a taunting grin at me, picked up his pace, and disappeared into the crowd up ahead.

By then, I felt no shame in losing a footrace to Zombie-Man. Whatever semblance of athletic pride I’d carried to the starting gate of the fifteenth Los Angeles Marathon flat-lined at Mile 21 when a sledgehammer of fatigue slammed me in the chest. From there on, I plodded forward in a crab-like, muscle-cramped gait, my legs filled with gelatinous sludge, my arms stone-heavy petrified fossils, each breath heaved through a pinhole in a plastic bag draped over my head and tied tightly around my neck. A vast herd of runners of all ages, shapes, and sizes passed me by – fat little kids, bone-thin octogenarians, a middle-aged squatty man with a rotund beer-belly, an old lady pushing a Dachshund in a baby stroller, a cowboy wearing a ten-gallon hat and snake-skin boots, twin Elvis impersonators running side by side. I didn’t care. After I hit THE WALL, excruciating pain crowded out all thoughts and feelings except for my desperate goal, a long-held dream, now a gasping nightmare, of teetering across a marathon’s finish line.

This death march went down on March 5, 2000. I was 52. Thirty years earlier, I’d taken up running in college to relieve stress and kept it up throughout my working life. I wasn’t fast, but I could run a long way at a slow pace. Somewhere along the line, the dream of completing a marathon got ahold of me, but my work schedule couldn’t accommodate the rigorous training required. Suddenly faced with an abundance of free time when I left Safeway in January, I signed up for the LA Marathon.

This death march went down on March 5, 2000. I was 52. Thirty years earlier, I’d taken up running in college to relieve stress and kept it up throughout my working life. I wasn’t fast, but I could run a long way at a slow pace. Somewhere along the line, the dream of completing a marathon got ahold of me, but my work schedule couldn’t accommodate the rigorous training required. Suddenly faced with an abundance of free time when I left Safeway in January, I signed up for the LA Marathon.

Being a slow runner, I set a snail-paced goal of finishing in 5 hours, an easy 11¾ minute per mile jog. Experienced marathoners recommend at least four months of training, five “short” runs on weekdays, beginning with 4 miles building up to 10, and one long run on the weekend, starting with 10 miles and ending with 20-plus. I’d been running a couple miles a day for years so I thought I could be ready in half the time. The eight weeks flew by, but I reached the 10-mile week-day standard and made it up to 18 miles on the weekend.

On March 5 at 7:30 am, 20,000 runners gathered in the starting pen on Figueroa Street in a torrential downpour. I stood at the back of the pack, peering through the monsoon at Mayor Riordan, perched on an elevated platform at the starting line. Laughing maniacally, his helmet of thinning white hair sopping wet, he shouted into a bull horn, “Welcome to sunny California” and fired the starting gun.

On March 5 at 7:30 am, 20,000 runners gathered in the starting pen on Figueroa Street in a torrential downpour. I stood at the back of the pack, peering through the monsoon at Mayor Riordan, perched on an elevated platform at the starting line. Laughing maniacally, his helmet of thinning white hair sopping wet, he shouted into a bull horn, “Welcome to sunny California” and fired the starting gun.

I was so far back I couldn’t move for a while, and even when the runners ahead of me lurched forward, I could only slow-walk. About fifty yards past the starting point, I finally had enough space to break into a trot.

Following Runner’s World magazine’s advice for first-time marathoners, I settled into a slow pace for the first half-marathon. I thought the rain would make the going more difficult, but it turned out to be an advantage. The temperature leveled off at a comfortable 60 degrees; my lightweight parka kept me dry; and my Nike’s flicked the water away.

As we ran through downtown, people clad in rain gear lined the streets. “Keep going! You’re doing great!” Volunteers at the USC Coliseum handed us cups of water and shouted encouragement. Farther on, someone bugled a cavalry charge from a second-floor apartment window. At Mile 8, lightning struck, and thunder boomed. We all gasped, then cheered, and ran on.

As we ran through downtown, people clad in rain gear lined the streets. “Keep going! You’re doing great!” Volunteers at the USC Coliseum handed us cups of water and shouted encouragement. Farther on, someone bugled a cavalry charge from a second-floor apartment window. At Mile 8, lightning struck, and thunder boomed. We all gasped, then cheered, and ran on.

Cresting a little hill at Mile 11, we came upon the red-and-blue flashing lights of an ambulance. Paramedics surrounded a runner down on his back in the street. Single-mindedly focused on running the race, none of us stopped. We didn’t even slow down.

The rain lightened at the halfway mark. In the cool mist, I kicked into overdrive. On a runner’s high, I ran seven-minute miles through Hancock Park, pumped uphill to Hollywood, and sped back down toward the heart of the city, cruising through Miles 17, 18, and 19.

Then the terrain leveled off. I started to feel strange. Hollowed out. Numb. In the mid-Wilshire District, the course took a sharp turn, but my rubbery legs kept going straight. To force my strides to make a wide arc to the left, I had to lean sideways at a thirty-degree angle like a guy on a motorcycle.

Then the terrain leveled off. I started to feel strange. Hollowed out. Numb. In the mid-Wilshire District, the course took a sharp turn, but my rubbery legs kept going straight. To force my strides to make a wide arc to the left, I had to lean sideways at a thirty-degree angle like a guy on a motorcycle.

To the naked eye, the grade moving along Wilshire Boulevard toward downtown looks flat. It is not. There is a one-degree lift. I know this because running 21 miles gives you a whole new definition of steep. Running over that slight, almost imperceptible incline felt like scaling Mount Everest without an oxygen tank.

All the people I had passed in my speed-run since the halfway mark, plus thousands more, overtook me, including Zombie-Man. I couldn’t keep up with any of them. Each torturous step required a supreme act of will. I slowed to a walk, then stopped and leaned over, propping my hands on my knees. I thought I was done.

All the people I had passed in my speed-run since the halfway mark, plus thousands more, overtook me, including Zombie-Man. I couldn’t keep up with any of them. Each torturous step required a supreme act of will. I slowed to a walk, then stopped and leaned over, propping my hands on my knees. I thought I was done.

A woman on the sidelines shouted to me. “Don’t give up!” Others chimed in. “Keep going! You can do it! Dig deep!” A runner going past me patted me on the back, “Come on, buddy. We’re almost there.”

A short stout lady trotted by me. I gazed at black letters on the back of her yellow t–shirt. “IT’S NOT THE DISTANCE. IT’S YOU.” My blurry brain struggled to assimilate the message.

Riveting my eyes to those words, I leaned forward and fell into a painful, staggering jog. Through Miles 24, 25, and 26, when the t–shirt’s letters grew smaller, I’d reach way down and somehow find the strength to reel them in. They’d fade again, and I’d bring them back. Again and again, they pulled me forward.

Riveting my eyes to those words, I leaned forward and fell into a painful, staggering jog. Through Miles 24, 25, and 26, when the t–shirt’s letters grew smaller, I’d reach way down and somehow find the strength to reel them in. They’d fade again, and I’d bring them back. Again and again, they pulled me forward.

The last 385 yards. Downhill. Thank you, Jesus.

At the intersection of Figueroa and Wilshire, a team of men from Little Tokyo wearing white and red headbands pounded big drums, an upbeat boom, boom, boom. A race official with binoculars perched on a catwalk identified runners by the numbers pinned to our jerseys and called out names. “Ken Oder, San Marino,” boomed over the loudspeaker.

I made a left turn, motorcycle style, onto Flower Street. Thirty steps to go.

A digital timer hung over the finish line. Big red numbers, 4:59:53 and ticking.

A digital timer hung over the finish line. Big red numbers, 4:59:53 and ticking.

I tried to sprint. I could not.

I stumbled across the line at 5:00:05.

A race proctor draped a foil blanket over my shoulders. He clipped from my shoelace the microchip they had sent us to record our times at the starting line, various checkpoints, and the finish line. Then he guided me to a grassy bank where I collapsed. Lying there cramped up, depressed that I’d missed my goal by five seconds, and exhausted beyond all imagination, I vowed never to run another marathon.

A few days later a package from the race officials came in the mail. My computer chip deducted the time it took me to reach the starting line. My official time was 4:56:06. I’d beaten my goal. No matter that 6,990 runners finished ahead of me, I was elated.

In two weeks, the soreness eased off. I started running again, a couple miles a day. In June, I upped it to 5, then 8 in August. In September I ran 15 miles on a weekend day.

I felt good. Real good.

Maybe I wouldn’t hit the wall with a full training regimen. Maybe I could break 4 hours.

On March 4, 2001, a cool day with a light mist, I ran LA XVI. I hit the wall, but not as hard. My time was 4:25:29, a 30-minute improvement. I figured if I could lop 30 minutes off my time each year, I’d break the world record when I turned 62, so I signed up for LA XVII.

I didn’t break the world record. I couldn’t even break 4 hours, but I kept trying. After all, it’s not the distance. It’s you.

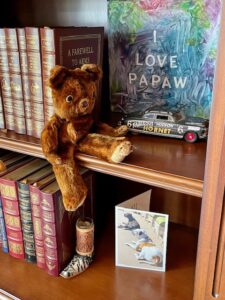

Last week I was rummaging around in a closet where we keep toys for our grandkids’ visits when I found a brown teddy bear at the bottom of a cardboard box. I was surprised to find him there. He and I go back a long way, but I hadn’t seen him in years. I carried him to the bed, sat down, and looked him over. Memories flooded over me.

Last week I was rummaging around in a closet where we keep toys for our grandkids’ visits when I found a brown teddy bear at the bottom of a cardboard box. I was surprised to find him there. He and I go back a long way, but I hadn’t seen him in years. I carried him to the bed, sat down, and looked him over. Memories flooded over me.

I was a little boy back then, too excited to care how my parents felt about giving me those gifts, but I know now, from my own feelings about my son’s first Christmas, how much that morning meant to them. I was their first child, and at that point still their only child, and that was the first Christmas I was old enough to understand the magic of Santa Claus. Their reward for their sacrifice was my unbridled joy, and to them it was priceless.

I was a little boy back then, too excited to care how my parents felt about giving me those gifts, but I know now, from my own feelings about my son’s first Christmas, how much that morning meant to them. I was their first child, and at that point still their only child, and that was the first Christmas I was old enough to understand the magic of Santa Claus. Their reward for their sacrifice was my unbridled joy, and to them it was priceless. When Jackie Paper was a little boy, he played with Puff the magic dragon in the imaginary wonderland of Honah Lee. A dragon lives forever. Not so with little boys. Jackie grew up and came to Honah Lee to play with Puff no more.

When Jackie Paper was a little boy, he played with Puff the magic dragon in the imaginary wonderland of Honah Lee. A dragon lives forever. Not so with little boys. Jackie grew up and came to Honah Lee to play with Puff no more. As I sat on the bed staring at him, the many happy Christmases of my youth came back to me, including my last Christmas at home with Mom, Dad, and my brothers. I was twenty, home on holiday break from UVA. Dad had been the preacher at Mount Moriah Methodist Church in White Hall, Virginia, for six years. Every year the church gave baskets of food and boxes of toys to poor families on Christmas Eve. I’d never joined the church members on the trips to deliver gifts. I always had a date or a party to attend, something fun to do, but that year Dad insisted I go along.

As I sat on the bed staring at him, the many happy Christmases of my youth came back to me, including my last Christmas at home with Mom, Dad, and my brothers. I was twenty, home on holiday break from UVA. Dad had been the preacher at Mount Moriah Methodist Church in White Hall, Virginia, for six years. Every year the church gave baskets of food and boxes of toys to poor families on Christmas Eve. I’d never joined the church members on the trips to deliver gifts. I always had a date or a party to attend, something fun to do, but that year Dad insisted I go along.  The shack’s door opened. Johnny Sipe stood in the doorway. In his early twenties, short and heavyset, with dark sunken eyes, he did his best to maintain a tight, twitchy smile as we sang the carol. His bone-thin pale girlish wife stood behind him, peeking timidly over his shoulder. A few verses into Silent Night, she retreated inside the shack and sat on the edge of a bed. In the flickering candlelight, I could barely see two little faces staring at us, the bed covers pulled up to their chins.

The shack’s door opened. Johnny Sipe stood in the doorway. In his early twenties, short and heavyset, with dark sunken eyes, he did his best to maintain a tight, twitchy smile as we sang the carol. His bone-thin pale girlish wife stood behind him, peeking timidly over his shoulder. A few verses into Silent Night, she retreated inside the shack and sat on the edge of a bed. In the flickering candlelight, I could barely see two little faces staring at us, the bed covers pulled up to their chins.  Most everything Cindy and I tried worked out for us. Some of that was because of effort and talent; some of it was because someone helped us climb out of a hole; and some of it was because each time we pushed all the chips into the middle of the table and bet against the odds, we won.

Most everything Cindy and I tried worked out for us. Some of that was because of effort and talent; some of it was because someone helped us climb out of a hole; and some of it was because each time we pushed all the chips into the middle of the table and bet against the odds, we won. At four in the morning our Pit Bull, P.D., stood on his hind legs with his front paws on my bed and nuzzled my arm with his nose. He and Zoey, our American Bulldog, usually sleep through the night, but they wake me to let them out if they need to go to the bathroom. As soon as I get up P.D. usually races down the stairs to the back door, but that night he walked over to his bed and laid down.

At four in the morning our Pit Bull, P.D., stood on his hind legs with his front paws on my bed and nuzzled my arm with his nose. He and Zoey, our American Bulldog, usually sleep through the night, but they wake me to let them out if they need to go to the bathroom. As soon as I get up P.D. usually races down the stairs to the back door, but that night he walked over to his bed and laid down.

When she was five months old, a dog breeder who’d lost his home to foreclosure begged my daughter to take her for a few days, then disappeared, and wouldn’t answer her calls. My daughter already had three dogs. She asked Cindy and me if we wanted Zoey. A few years earlier, two fourteen-year-old dogs we’d raised from puppies

When she was five months old, a dog breeder who’d lost his home to foreclosure begged my daughter to take her for a few days, then disappeared, and wouldn’t answer her calls. My daughter already had three dogs. She asked Cindy and me if we wanted Zoey. A few years earlier, two fourteen-year-old dogs we’d raised from puppies  When our grandkids came over, she got excited and played too rough. Knowing Zoey was a quick study, I hired a dog trainer to break the habit. A nice young woman in her late twenties, the trainer was gentle with Zoey, but firm. Zoey didn’t like the firm part. She hid under the bed at the beginning of each session, and when I pulled her out in the open, she stood behind me and timidly peeked around my leg at the trainer.

When our grandkids came over, she got excited and played too rough. Knowing Zoey was a quick study, I hired a dog trainer to break the habit. A nice young woman in her late twenties, the trainer was gentle with Zoey, but firm. Zoey didn’t like the firm part. She hid under the bed at the beginning of each session, and when I pulled her out in the open, she stood behind me and timidly peeked around my leg at the trainer.