The Plumber

I army-crawled under the house and pointed my flashlight at the far corner. Through the haze of golden dust motes and silver spider webbing, I saw the aluminum duct lying on the ground. My goal was to reattach it to the bedroom floor-vent above it.

In my summer job as a plumber’s helper, I’d crawled under houses before. Musty, filthy, insect-infested, darker than a moonless night, it was never a pleasant experience, but the underside of this antebellum manse was the worst so far. Since its construction, the ground had shifted and the ancient floor joists had warped. In some places the clearance was less than six inches.

Slithering along on my belly, I came to a joist that blocked my path. I scooped out a trough in the dirt, rolled over on my back, and scuffed forward. I pushed my head through, but my chest wouldn’t clear. Squirming around, I got stuck so tightly I couldn’t move. Pinned like an insect on a poster board, I was fighting off claustrophobic panic when I heard a dry rustling sound to my left.

Alarmed, I cast my light in that direction. A black snake lay coiled an arm’s length away, staring at me, its eyes glowing like little diamonds, its tongue flicking in and out.

Alarmed, I cast my light in that direction. A black snake lay coiled an arm’s length away, staring at me, its eyes glowing like little diamonds, its tongue flicking in and out.

Merriam-Webster defines ophidiophobia as the “abnormal fear of snakes.” The genius who put the word “abnormal” in there obviously never squared off against a snake under a house.

I tore all the flesh off my chest lurching out from under that joist, set a land-speed record for a man crab-scuttling on his back, and flopped through the crawlspace opening into the twilight. After checking to make sure the black racer hadn’t followed me, I collapsed on the grass, my heart pounding as loud and fast as the kettledrums in Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

This all went down at the tail end of a long hard day. Weeks earlier, the plumber, my boss, had landed a subcontract installing air conditioning systems in a housing development in Charlottesville. He trained me to run the ductwork and rough-in the vents, then hired Gilly Frazier and told me to teach him to do what I did.

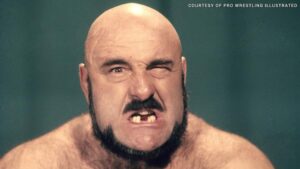

Among the hundreds of people I’ve worked with over my long life, Gilly ranked at the bottom in intelligence. Sixteen years old, five-five and 120 pounds with flaming red hair and a freckled face, he sported a cast on his forearm his first day on the job. When I asked about it, he said his daddy took him and his brother, Floyd, to a wrestling match in Charlottesville where some character named Mad Dog jumped off the ring’s turnbuckle onto an opponent lying flat

on the mat. Floyd came up with the bright idea of reenacting the match in their backyard, whereupon he jumped off a fence post onto Gilly’s forearm, snapping it like a brittle stick. “Floyd’s a dumbass,” Gilly said, doubling over in a fit of giggling, blissfully unaware that the bigger dumbass might be the brother who lay still while Floyd’s size twelves came crashing down on his arm.

Gilly said he dropped out of school because it was a “waste a time. Don’t larn nothin’. Cain’t figger what they’s talkin’ ‘bout.” He couldn’t figure what I was talking about either. He forgot everything I told him before I could finish telling him. With Gilly in tow, I had to work twice as hard to keep up with our production schedule.

Despite Gilly’s help, I’d finished installing an AC system by quitting time that day when the plumber got an emergency call to repair the AC in an invalid’s bedroom in the old manse, drove us there, diagnosed the problem, and sent me under the house while he and Gilly waited in the bedroom at the AC vent.

I was still stretched out on the grass trying to recuperate from acute ophidiophobia when the plumber and Gilly walked up on me. In his late forties, short and paunchy, the plumber was a good guy, but he operated on a tight budget and slow-downs on the job lit his short fuse. When he found me lying flat on my back in a catatonic stupor on his nickel, he exploded.

“What the hell are you doing?” he boomed.

I struggled to my feet. “I ran into a snake under there,” I said defensively.

“What happened to your chest?” he said.

I looked down to see crimson bloodstains on my t‑shirt and felt the sting of abrasions for the first time. I told him what happened. “There’s not enough clearance,” I said. “I couldn’t have made it to the duct even if the snake hadn’t showed up.”

The plumber’s temper usually cooled as quickly as it flared. This blast followed the pattern. “Sorry I yelled at you. We’ll put disinfectant on those cuts when we get home, but first we’ve got to find a way to fix the AC. Old man Woodson can’t breathe in this heat.”

The plumber knelt and flashed his light in the crawlspace. “The snake’s gone, but you’re right about the clearance. You can’t make it back to the corner.” He peered into the space for a while, then stood, and turned to Gilly. “It’s a tight fit, but you’re skinny enough to slip through.”

Gilly’s eyes widened. “It’s too dark,” he said.

“Take my light.”

Gilly swallowed hard. “I cain’t do it.”

“Don’t worry about the snake. He’s long gone. They’re more afraid of us than we are of them.”

“I ain’t scared a snakes.”

“Good. Then crawl under there and fix the duct so we can go home.”

His face twitching, Gilly backed away. “I don’t want to!”

The plumber’s tight-budget volcano erupted. “The hell with what you want! I pay you to do what I want! Get under there! Now!”

It was obvious where this was headed. In the month we’d worked together Gilly told me things he was ashamed to admit to most people. I knew why he couldn’t crawl under the house. I could tell the plumber and save Gilly’s job, but I’d carried him on my back like a dead body all day every day since he’d been hired. Stay out of it, I told myself.

I don’t think it was the tears sliding down Gilly’s freckled cheeks that got to me. More likely, it was the cumulative effect of a string of tell-tale signs: a purplish healed-over scar above his eye I’d noticed his first day of work, a discolored knot on his forehead that came and went a week later, red marks that encircled his throat shortly after that, and my growing doubts about his plaster-cast story.

“He’s afraid of the dark,” I said to the plumber.

“Who asked you to butt in?” the plumber shouted, turning on me.

“Gilly’s afraid of dark enclosed spaces,” I said evenly. “He has vivid nightmares about being locked in a closet all night long.”

A look of concern came across the plumber’s tense face.

“He dreams about that dark closet every night,” I said, giving the plumber a long, knowing look, hoping he’d pick up on my suspicion that Gilly’s nightmare wasn’t just a dream.

We both looked at Gilly. He kept his head down and said nothing. The plumber stared at him for a long time, then knelt down, and flashed his light under the house.

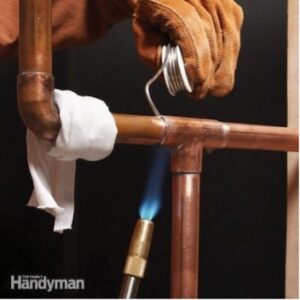

“The duct’s on the ground right below the vent,” he said. “The line’s joints held together.” He looked up at me. “You think we can reconnect it from the bedroom?”

I thought about it. “We should be able to reach it from above. If I can lift the line and nail the duct to the joists without the joints pulling apart, it’ll work.”

“Give it a try.”

It worked.

The next day, the plumber assigned Gilly to the senior man on the AC subcontract. A few days later, he told the plumber Gilly was untrainable.

I thought the plumber would fire him then, but instead he put him on a job running water lines and laying sewer pipe. Traditional plumbing is more straightforward than heating and air. Most of what you need to know springs off the trade’s three primary rules: “Hot on the left; cold on the right; and s*** don’t run uphill.” I hoped Gilly could catch on to it. When I left to return to UVA, he was hanging on to the job by his fingernails.

Three years later, I ran into him at Wyant’s Store in White Hall. He still worked for the plumber and was living on his own in Brown’s Cove. I didn’t see any fresh tell-tale signs.

As I watched Gilly’s beat-up pickup rattle off down the road to Crozet, I thought about the plumber paying him good money he couldn’t spare week after week, refusing to give up on him, stubbornly determined to unearth whatever talent lay buried deep down inside that sad kid.

It made no sense from a business standpoint, but like I said, the plumber was a good guy. Really good.

Post Script: The fear of snakes is among the most common of the 120 recognized phobias, afflicting 56 percent of adults, while Gilly’s fear of the dark, Nyctophobia, and its first cousin, Claustrophobia, each plague about 12 percent. Some extremely rare phobias must be difficult to cope with, like Baraphobia, the fear of gravity; Omphalophobia, belly buttons; Optophobia, opening your eyes; and my personal favorite, Hippopotomonstrosequipedaliophobia, the fear of long words.

I was tooling down Huntington Drive in my two-toned beige and brown 1954 Hudson Hornet when smoke billowed from the hood. I hit the brakes; the Hudson lurched violently to the right; the front tire rammed into the curb; and the engine stalled out.

I was tooling down Huntington Drive in my two-toned beige and brown 1954 Hudson Hornet when smoke billowed from the hood. I hit the brakes; the Hudson lurched violently to the right; the front tire rammed into the curb; and the engine stalled out.

Lester towed the Hudson to Brad’s shop. He “fixed” the brakes again. Since he couldn’t find anything wrong with the radiator, we tried a different engine coolant. On the way home, the interior rear-view mirror fell from its mount and shattered on the floorboard. I drove to O’Reilly Auto Parts in San Gabriel to see if I could pick up a replacement on the cheap. The elderly clerk who waited on me was familiar with Hudsons. When I mentioned my recurring boiling-over adventures, he asked if he could take a look.

Lester towed the Hudson to Brad’s shop. He “fixed” the brakes again. Since he couldn’t find anything wrong with the radiator, we tried a different engine coolant. On the way home, the interior rear-view mirror fell from its mount and shattered on the floorboard. I drove to O’Reilly Auto Parts in San Gabriel to see if I could pick up a replacement on the cheap. The elderly clerk who waited on me was familiar with Hudsons. When I mentioned my recurring boiling-over adventures, he asked if he could take a look.

I began to think the Hudson had become my Red Chief. In O. Henry’s short story, The Ransom of Red Chief, a couple of miscreants kidnap a boy to extort a ransom from his rich dad, but the kid is such a holy terror the dad is glad to be rid of him and won’t pay. When the kid pretends he’s the fierce Red Chief, ties one of the kidnappers to a stake, and sets his pants on fire, the bad guys end up paying the dad a healthy sum to take him back.

I began to think the Hudson had become my Red Chief. In O. Henry’s short story, The Ransom of Red Chief, a couple of miscreants kidnap a boy to extort a ransom from his rich dad, but the kid is such a holy terror the dad is glad to be rid of him and won’t pay. When the kid pretends he’s the fierce Red Chief, ties one of the kidnappers to a stake, and sets his pants on fire, the bad guys end up paying the dad a healthy sum to take him back.

Mom woke me at dawn. I washed up, put on my new school clothes, and grabbed my Roy Rogers lunch box. She walked me down our dirt driveway and held my hand while we stood on the shoulder of Route 60, waiting for the school bus.

Mom woke me at dawn. I washed up, put on my new school clothes, and grabbed my Roy Rogers lunch box. She walked me down our dirt driveway and held my hand while we stood on the shoulder of Route 60, waiting for the school bus.

My stomach did a backflip.

My stomach did a backflip. Robert stopped crying when he saw me and clamped his sweaty hand onto mine. I tried to jerk free, but he held on like his life depended on it. He scooted his chair closer to mine and grabbed my arm with his other hand. I couldn’t make him let go, so we sat like that until the principal finally returned, disentangled me from Robert, and took me back to my class.

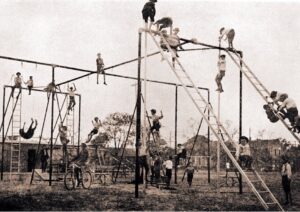

Robert stopped crying when he saw me and clamped his sweaty hand onto mine. I tried to jerk free, but he held on like his life depended on it. He scooted his chair closer to mine and grabbed my arm with his other hand. I couldn’t make him let go, so we sat like that until the principal finally returned, disentangled me from Robert, and took me back to my class. The first grade turned out to be fun for the most part – storytime, craft time, nap time. Recess was the best. They turned us loose on a playground that would qualify as a killing field under today’s safety standards. No plastic slides, rubber mats, or guardrails, and a fall from the giant iron jungle gym’s monkey bars held the promise of permanent paralysis, if not outright death.

The first grade turned out to be fun for the most part – storytime, craft time, nap time. Recess was the best. They turned us loose on a playground that would qualify as a killing field under today’s safety standards. No plastic slides, rubber mats, or guardrails, and a fall from the giant iron jungle gym’s monkey bars held the promise of permanent paralysis, if not outright death. He turned around and smiled at me with a wounded look in his eyes, sad and hurt, but mean at the same time. He reached over the seat, wrapped his hands around my throat, and began to choke me. I don’t know if the other kids didn’t notice or just didn’t care, but none of them did anything.

He turned around and smiled at me with a wounded look in his eyes, sad and hurt, but mean at the same time. He reached over the seat, wrapped his hands around my throat, and began to choke me. I don’t know if the other kids didn’t notice or just didn’t care, but none of them did anything.

Yeah. He almost crashed in the last race.”

Yeah. He almost crashed in the last race.”