The Blind Date

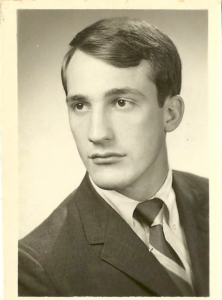

Near the end of my third year at UVA, some of my fraternity brothers planned to caravan to Mary Baldwin College to take their girlfriends to The Rafters, a dance hall with a live band. One of them was engaged to a Mary Baldwin senior, who was legendary for setting up successful blind dates. She offered to match me up with one of her friends. My experience with blind dates had been disastrous, to put it mildly, but her reputation convinced me to sign on.

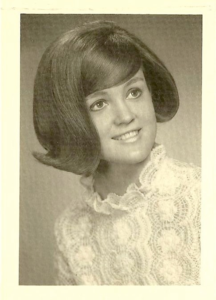

Mary Baldwin sits on the side of a hill in Staunton. We pulled to the curb at the foot of a flight of stairs that climbed to a yellow building fronted with massive white columns. We entered the lobby; the second floor doors opened; and ten girls came down the steps single file. One of them caught my eye. Auburn hair, chin length, flipped up on one side, stunning hazel eyes. I wondered which lucky guy would be paired with her.

When my friend’s fiancé introduced me to my date, the girl with the auburn hair flashed a pixie grin that took my breath away.

We had a lot of fun that night, and I drove back to UVA in a daze.

I asked her out again and she accepted.

On our third date, I gave her my fraternity pin. “Pinning” was a big deal back then, sort of a pre-engagement commitment. I was rushing it big-time, but she didn’t turn me down, so I thought maybe I had a chance.

Then the school year ended, and I despaired. She’d planned to graduate in three years. To finish the few remaining classes she needed, she’d enrolled in summer school at Boston University. She didn’t intend to return to Mary Baldwin. I was committed to a job in Virginia for the summer and had another year at UVA still to go. I thought I’d never see her again.

In a great gesture of friendship, one of my fraternity brothers offered to drive me to Boston to see her that summer. I took a week off from my job and spent it with her.

She took me to one of her classes. A guy who played guitar for The Jefferson Airplane sat in the row behind us. A fullback on the Boston University football team sat on the other side of her. They were very interested in her, and they were both good-looking, nice guys. I hated their guts.

We were sitting on a blanket having a picnic lunch in front of the camel exhibit at the Franklin Park Zoo in Boston when I asked her to consider returning to Mary Baldwin for another year.

“Why?” she said.

“I want to keep seeing you.”

She looked at me curiously, as though she didn’t understand, and I realized I had to tell her the truth. I swallowed hard. “I want you to marry me after graduation.”

I don’t remember much about the camels, the zoo, or the rest of the day. She was all I could think about after she said she wanted to marry me, too.

That fall, I met her family. I overheard a neighbor talking to her father. “What says they’re going to get married?” the neighbor asked. “That old pin, I guess.” The neighbor wouldn’t let up. “Is he going to give her an engagement ring?” A long pause. Then, “I don’t know.”

I planned to give her an engagement ring, but being flat-out broke, I hadn’t figured out how I would spring for it. Back at school, I asked her what kind of ring she wanted, thinking it would be a traditional diamond. She launched into a detailed description of a green jewel surrounded by a circle of little diamonds on a gold band. “A little green flower,” she said, giving me that grin that got me in trouble in the first place.

I knew nothing about jewelry, but I figured a little green flower would be hard to find. The first ring I saw in the first jewelry store I walked into sat in the center of a glass case near the door – an emerald surrounded by a circle of diamonds perched on a gold band. A little green flower.

I thought it was meant to be! Until the jeweler told me its price. When I recovered my voice, I explained that I had to have that ring even though I couldn’t pay for it. The jeweler returned the ring to its red satin bed inside the glass case and turned the key on the lock.

Short of armed robbery, I couldn’t think of a way to get that ring.

“Why don’t you sell your stamp collection?” my mother said.

When I was a little boy, my mother and I would save our loose change. Every couple weeks, she would take me to a stamp collector’s store in Williamsburg and drop me off while she grocery-shopped, and I pieced together a little collection of stamps that didn’t cost much.

“My stamp collection’s not worth anything,” I told my mom.

“Some of those stamps are pretty old,” she said. “Give it a try.”

I went to a collector’s shop in Charlottesville. When the owner gave me his bid, I almost fainted. My mother was right. Over the fifteen years my stamps lay in a shoebox in my bedroom closet, a few of them had become valuable. The sale got me within striking distance of the ring’s price, and I borrowed the rest.

The little green flower burned a hole in my blue blazer’s side pocket as I drove my auburn-haired blind date down Route 250 at noon toward the new Chinese restaurant everyone was talking about. It was closed. I sped back toward Charlottesville and drove around frantically for what seemed like seventeen hours, looking for a romantic lunch spot where I could give her the ring. There was no good place!

Desperate, I lurched off the street into the Howard Johnson’s parking lot and pulled her by the hand into the dining room. During the six years it took to get a waitress to take our order, I began to chicken out. I had proposed in front of a camel. Now I was giving her an engagement ring at a Howard Johnson’s. I was blowing it!

It didn’t matter. I had to get that ring on her finger before I had a nervous breakdown. I put my hand in my pocket to draw strength from the flower. You have THE RING, I told myself. That’s what’s important.

“You know that engagement ring?” I said.

“Yeah?” An unsuspecting tone.

“Which hand does it go on?” Because I was so stupid I truly didn’t know.

“This one,” she said, extending her left hand across a plate of fried clams.

“Which finger?” I’m not that stupid. I was stalling while I tried to pull myself together.

She showed me her ring finger.

I took a deep breath, pulled the ring out of my pocket, and slipped it on. It only made it half-way down her finger because she clenched her fist with superhuman strength, crushing my fingers, both of us shaking all over, she from excitement, me from excruciating pain.

We got married the weekend after graduation. We had three children. Four grandchildren came along a generation later. We celebrate our forty-ninth anniversary next month.

My blind date still wears the little green flower. As I wrote this, just to see if I could raise that pixie grin, I asked her what she thought my old stamp collection would be worth today if we’d held on to it.

“Not as much as my ring,” she said.

She’s right about that.

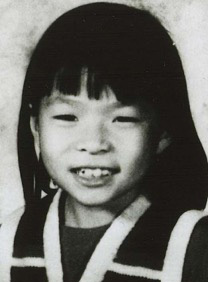

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

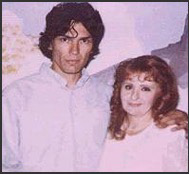

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.