The Great Train Wreck

About fifteen years ago, I got interested in ancestry research. At a family reunion, I told everyone I intended to trace our family tree as far back as I could go. One of my nephews gave me the hairy eyeball. “That’s not a good idea,” he said. “You may find out things we don’t want to know.”

I thought his concern was ridiculous and ignored his warning. About a month later, I found records on Ancestry.com about William Odor, who turned out to be our most famous family member by far. Born in Illinois in 1844, he gained national notoriety during the summer of 1870. The story of his rise to country-wide prominence begins in the spring, normally a season of hope and optimism.

On May 12, 1870, a Missouri Pacific Railroad passenger train pulled into Eureka, Missouri, before dawn. It was due to arrive in St. Louis at 6:00 a.m. A freight train left St. Louis about the same time, headed for Eureka. In those days railroad companies put down a single track and trains traveled in both directions on it. When two trains were scheduled to travel toward each other, one of the trains was required to pull off onto side rails, which were spaced at intervals along the single track. Under the Missouri Pacific rule, passenger trains had the right of way over freight trains, and freight trains were responsible for giving it to them.

The dispatcher in St. Louis told the freight train’s conductor, William Odor, that the freight train could proceed toward Eureka for thirty minutes, but after that, it would have to give way to the passenger train by pulling off on a side spur.

The passenger train’s engineer, J.P. Jackson, eased his train out of the Eureka station a little after 5:00 a.m. About a mile and a half into the trip, the passenger train entered a sharp turn, and Jackson saw the puffing smokestack of a freight train barreling around the bluff at full speed toward him. He hit the brakes and reversed engines.

The freight train’s engineer, Joseph Tracy, tried to brake his train, too, but there was no hope of stopping an engine of that power at that speed pulling that much weight.

The engineers and conductors on both trains jumped free just before they collided. The two locomotives reared up on their back wheels like wild stallions fighting one another. The impact of the crash compressed the passenger train’s six cars into its locomotive like the folds of an accordion, shredding them into strips of metal and wood. The engines then slid down an embankment, dragging the cars and passengers with them. Corpses, body parts, and injured survivors littered the tracks and embankment. Nineteen people were killed. Thirty were injured, eighteen of them with amputated limbs or collapsed internal organs.

Jackson and the passenger train’s conductor did their best to help the survivors. The freight train’s engineer and conductor, Tracy and Odor, ran away. As best I can tell, Tracy was never found. Odor was tracked down the following day and detained.

A coroner’s inquest determined that he was at fault. As the conductor of the freight train, it was his job to keep the train on schedule. He ignored the dispatcher’s instructions that he could run no more than thirty minutes before pulling over to give the right of way to the passenger train. The freight train had been on the track 45 minutes when it hit the passenger train. Odor’s defense was that there must have been something wrong with his watch, the passenger train conductor’s watch, or the clock at the St. Louis station. The coroner’s jury didn’t buy it. They found him culpable; the prosecutor indicted him for multiple counts of manslaughter; and the court jailed him pending trial.

Newspapers all across the country ran stories about the train wreck and its aftermath for months following the collision. Every article in every newspaper highlighted William Odor’s wanton recklessness as the cause of the tragedy. Punchinello, a New York weekly satirical magazine, called for the death penalty (probably tongue-in-cheek), making a pun with my family’s name. “(W)e fervently desire to have this ODOR neutralized … with strychnine.”

Sigh.

Mercifully for me and William Odor’s other descendants, the press grew weary of the train wreck by the end of the summer and his ignominy faded into the mist of history. I could find no records about the rest of his life. I don’t even know what happened to him in the criminal proceedings, but given the notoriety of the case and the number of deaths and injuries, it’s likely he served a long stretch in a Missouri prison.

For years I searched for some counterbalancing heroic ancestor in the family tree. One guy was a fifth cousin of Daniel Boone, but if you do much ancestry research, you’ll find that almost everyone alive today in the United States can claim some distant connection to the famous pioneer, the reason being that almost every member of the Boone family spawned ten to twenty kids.

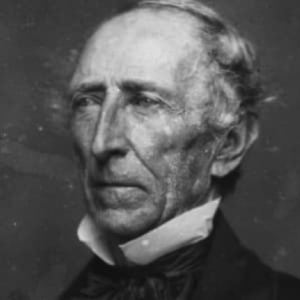

Other than that, all I could dig up was a third cousin twice removed from President John Tyler’s second wife. Tyler was William Henry Harrison’s Vice President. When Harrison died of pneumonia, Tyler became the tenth President of the United States. He was wildly unpopular. The first impeachment resolution ever introduced in Congress against a President was aimed at him. His own party, the Whigs, rejected him when he tried to run for reelection, and most historians rank him alongside James Buchanan and Millard Fillmore as a bottom-feeder among U.S. Presidents.

So my family’s only pathetic shot at genealogical redemption for William Odor’s Missouri slaughter is a tenuous connection to one of the crappiest presidents who ever lived.

But that’s not the worst of it. I made the mistake of researching my wife’s family history, too. One of her branches goes back to William the Conqueror. Her ancestor took care of William’s horses on the battlefield. Her tree has royal Plantagenet family English lords and ladies hanging all over it. One of her forefathers, nine generations back, was the brains behind the Virginia Company which financed and founded the Jamestown Colony. Another one was an early Jamestown settler, a big hero who fought off scores of Powhatan warriors during the Indian Massacre of 1622 that wiped out more than half the colonists. There’s an island on the James River near Richmond named after that branch of her family. There’s more, but I don’t want to talk about it.

For the half-century we’ve been married, most everyone who knows my wife and me has seen fit to remark sooner or later that I married up. To maintain marital bliss, I’ve kept my mouth shut over the many years, while secretly telling myself they were wrong.

Now this.

I should have listened to my nephew.

Post Script: Maybe there’s still hope. I just found out there’s a Venezuelan named Rougned Odor, who plays second base for the Texas Rangers. I can’t pronounce his first name and he’s only batting .250, but hey, he’s in their starting lineup. There’s definitely a family resemblance between us, don’t you think? The ears are a match for sure.

Mom worked there, too, and Dad fell for her. She was seventeen when they eloped, running across the state line to North Carolina, which didn’t require her parents’ consent to tie the knot.

Mom worked there, too, and Dad fell for her. She was seventeen when they eloped, running across the state line to North Carolina, which didn’t require her parents’ consent to tie the knot.

He had a stroke when he was 86. One month later, he returned to the little church’s pulpit, this time in a wheel chair, and Christian-soldiered on until old age broke him down.

He had a stroke when he was 86. One month later, he returned to the little church’s pulpit, this time in a wheel chair, and Christian-soldiered on until old age broke him down.