Turning Seventy

My seventieth birthday rolled on by this month. It’s hard to convince myself I’m not old with that big number hanging around my neck. The physical evidence works against me, too.

My body parts are wearing out. My sinuses shut down first. A surgeon roto-rooted out everything from my upper lip to the back of my skull so I could breathe again. Cataract surgery on both eyes came next. A double hernia repair after that. Then my gall bladder tried to kill me, going gangrenous for no apparent reason. They cut it out on Christmas Day.

Last month, they replaced my left knee. I get a new right knee next month. A woman in my rehab class has two new knees, two new hips, and a new shoulder. Makes me wonder why we don’t just replace everything all at once and get it over with.

An Italian neurosurgeon, Sergio Canavero, thinks this piecemeal approach to failing body parts is inefficient. He plans to fix everything in one fell swoop by transplanting the head of a man onto a healthy body in a two-part process he calls HEAVEN (head anastomosis venture) and GEMINI (spinal cord fusion). He’s scheduled the world’s first head transplant for October of this year in China. You can read about it here: http://www.newsweek.com/head-transplant-sergio-canavero-valery-spiridonov-china-2017–591772.

When I mentioned the head transplant idea to my wife, she threw cold water on it. “It won’t work,” she said.

“Why?”

“You’ll be stuck with your head.”

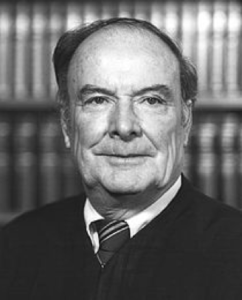

While I feel strongly she could have stated her opinion with a tad more sensitivity, I agree that my head won’t cut it, so to speak. My face has more lines than a Virginia road map; my turkey wattle is so jowly I have to watch my back on Thanksgiving Day; and my hair is falling out! My hairline’s been receding since I was thirty. My son used to joke that my forehead was a fivehead. Pretty funny at the time, but I stopped laughing between there and my current ninehead, which is working its way toward the dreaded twelvehead, where your hairline meets the back of your neck.

There are no attractive ways to fix this. There’s the Propecia-driven Trump comb-over. Very complicated and requires follicles thirty feet long. On the other side of the aisle are the Biden/Schumer hair plugs, where, close up, you look like you’ve been run over by a sewing machine. Then there’s the late Congressman/ex-convict James Traficant hair piece, otherwise known as a dead squirrel. I don’t know. Maybe I’ll just polish my twelvehead and live with it.

There’s a lot more to being seventy than physical challenges, though. My memories go back a long way. I’m so old I remember when my family didn’t have indoor plumbing. Our toilet was an outhouse in the back yard behind the chicken coop. We drew well water with a hand pump and bathed in a wash tub. We got running water in the house when I was five. I still remember the first hot shower, the abundance of water cascading over my shoulders, the steam, and the refreshing feeling of being really clean.

I’m so old I remember not having a television set. I sat cross-legged on the floor by the radio and listened to Gunsmoke and The Lone Ranger, imagining the people and scenes. Radio narration is a lost art today, which is too bad. I can still hear the deep voice of The Shadow’s guy. “Who knows what evil lurks in the hearts of men? The Shadow knows!” His rumbling creepy laugh gave me goosebumps.

We got a black and white television set when I was six. Most of the children’s shows were filmed live, which wasn’t always a good thing. The Pinky Lee Show featured a little song and dance guy with a checkered hat and suit. During a live show, he grabbed his chest, choked out, “Somebody please help me,” and keeled over, traumatizing children all across the nation. “Pinky’s dead,” I told my Mom. “It’s part of the show,” she claimed, but having learned the truth about the great Santa Claus fraud the previous winter, I no longer believed anything she said. When Pinky didn’t return to the show, I knew I was right. For sixty-three years, I thought Pinky died of a heart attack that day. Researching for this post, I learned that he fainted from a nasal infection, recovered, and lived another forty years, dying in 1993 at the age of 85. It pisses me off that no one told me, but I’m so old I can’t do anything about it because everyone to blame is dead.

I’m so old polio still crippled and killed children when I was a kid. The Salk vaccine came out in 1953. We waited in long lines in grade school for the shot. Today’s hypodermic needles are so slim and delicate you don’t feel a thing. Back in the 50’s, the needle felt like an ice pick. Waiting our turn in line, we were scared to death. I almost threw up from nerves. One kid fainted. When your turn finally came, the nurse held you tight while the doctor stabbed you with the ice pick. Most of us walked away bawling, but none of us got polio.

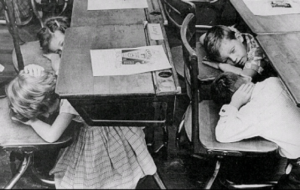

I’m so old I learned the nuclear attack duck and cover drill in the second grade. The teacher would yell, “Duck!” We ducked under our desks and assumed a tucked position. “Cover!” We put our hands over the backs of our necks. We stayed there until she gave us the all-clear.

In the fourth grade, I went on a school field trip to the city’s fallout shelter. It was a gloomy place, a football-field-sized root-cellar with generator-powered lights, ventilators, and shelves of canned goods and water. The shelter’s director gave a talk and then took questions. A girl standing behind me asked, “How long will we have to stay here?” The director answered with a wall of words. When he finished, the girl whispered, “They don’t know.” A boy asked if there was room in the shelter for everyone in the city. This one the director answered straight up. “No,” he said. “Every family should build its own shelter.” Very few families had a shelter. My family didn’t have one. I lost sleep over that for a few nights, but children can block out horrific thoughts. I did then. I still do.

I’m so old I was in high school when the principal came over the PA system and told us President Kennedy had been killed. There were scattered gasps and cries, then quiet. They called off school early. In the halls and on my bus ride home, where teenage enthusiasm and mischief always reigned, no one said a word. I’ll never forget the dead silence of that afternoon.

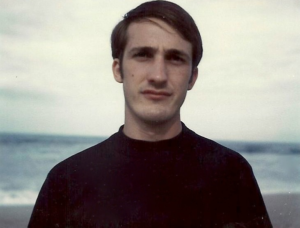

I’m so old I went to UVA when all the students were white males. We were Virginia Gentlemen. We wore coats and ties to class. We lived by an Honor Code. Gentlemen didn’t lie, cheat, or steal. There were no degrees of honor. The slightest infraction resulted in expulsion from the school and the community of gentlemen. A Virginia Gentlemen was allowed, however, to board a bus with a keg of beer in the back, drink all the way down the road to one of Virginia’s all-girl schools, and not having seen a woman for a month, go partying with a blind date, who hadn’t seen a man for a month. Thank God for that, or I never would have met my wife.

I’m so old I’ve been married for forty-eight years to a woman I still love.

I’m so old my children have grown up to become people I admire.

I’m so old I have four grandchildren who melt my heart when they call me Papaw.

I’m so old my time is my own to spend as I choose, however unwisely. Without this freedom and the perspective of age, I would never have found the late-in-life writing dementia that inspired me to pen my novels and to inflict this blog upon all of you.

I could go on and on, but I’ll rein it in, for your sake. I’ll just say this. I’m seventy years old; I’ve lived a long full life; I’ve still got a good ways to go; and you ain’t seen nothin yet.

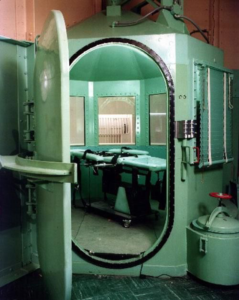

The cells on death row are windowless concrete boxes, about five by nine feet with very little head clearance. A strong man can mount a formidable defense from a rear corner. The guards couldn’t get Marshall out of his cell with normal force.

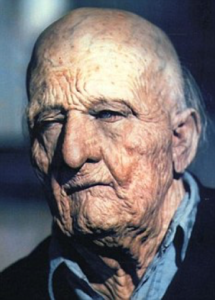

The cells on death row are windowless concrete boxes, about five by nine feet with very little head clearance. A strong man can mount a formidable defense from a rear corner. The guards couldn’t get Marshall out of his cell with normal force. This approach has not worked for California. It leads all states with 750 people sitting on death row. The average direct appeal now takes 22 years to move from sentencing to a decision. Tacking on lengthy federal appeals, a California death sentence is tantamount to life without parole. The state hasn’t executed anyone since 2006 and 90 inmates are over 65 years old, some of their crimes dating back 40 years.

This approach has not worked for California. It leads all states with 750 people sitting on death row. The average direct appeal now takes 22 years to move from sentencing to a decision. Tacking on lengthy federal appeals, a California death sentence is tantamount to life without parole. The state hasn’t executed anyone since 2006 and 90 inmates are over 65 years old, some of their crimes dating back 40 years.