The Cancer Club

My interoffice phone line rang. “Hey, Ken. It’s Paul. Can you come up to my office?”

“Sure.”

I climbed the inside fire stairwell from floor 43 to 46 and walked around the tower to Paul’s office. Tall and lean with dark brown hair, he sat at his desk, smoking a cigarette. “Close the door,” he said.

I closed it and sat in a chair across from him, my back to the bank of windows that looked out over LA.

He stubbed out his Marlboro and looked me directly in the eye. “I have cancer.”

I couldn’t process most of what Paul said after that. About all I remember are the words “aggressive” and “late stage.”

I cried.

In 1990, Paul and I were in our early 40’s, and we were attorneys with the law firm, Latham and Watkins. If I had ranked my friends back then, he would have placed in the top ten.

I pulled myself together. “Is there anything I can do?”

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

We talked for a long while about fun times we’d shared. Then he said he had to call the next friend on his list. We hugged. I went back to my office, closed the door, and cried some more.

He was gone in three months. An emotional wreck at the funeral, I got it together long enough to give my condolences to his wife. She told me Paul had treasured our friendship, and the way she said it, I knew it was true. I’ve carried that with me ever since.

Thirty-three years later, I noticed a small mole on my shoulder near my neck.

Because Cindy is fair-skinned and susceptible to melanoma, we follow a regimen of six-month checkups with a dermatologist. At the next exam, I asked him to look at the mole. “It’s nothing to worry about,” he said. His verdict remained the same for two years.

Last spring the mole grew larger and darker. One afternoon in June, my daughter and I were in the pool watching my grandkids. “What’s that on your shoulder?” Chelsea said.

“Just a mole. The doctor says it’s nothing.”

“I don’t know, Dad. It looks bad.”

That night I awoke from a sound sleep at 3 am. My first conscious thought came to me in a clear quiet voice: “Get that mole off your shoulder, or it will kill you.”

It scared me bad. I went to the dermatologist. He again said the mole was harmless.

“I want to take it off,” I said.

He agreed to remove it, gave me a shot, and sliced it off. “There’s dark tissue under the mole,” he said, sounding concerned. He cut into it.

“I only gave you a local. Are you in pain?”

It was killing me. “No pain,” I said.

He cut deeper. “You must be in pain.”

My shoulder was on fire. “I’m fine. Make sure you get all of it.”

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

The dermatologist’s sense of urgency alarmed me. “How bad is this?” I asked.

“Hopefully, we caught it early. If it hasn’t metastasized, you should be all right.”

I hung up the phone and stared at it. The mole had appeared two years ago, but the cancerous tissue under it may not have been there as long. The surgeon will remove it, and I’ll be okay, I thought. I decided not to tell anyone until I knew more.

A few days later I met with the surgeon. In his fifties with a full head of gray hair, he told me my form of cancer, melanoma beneath the skin, was rare. It could have taken root in another part of my body and spread to that spot, or if it originated in my shoulder and had been there awhile, it could have spread to other locations. “I need to know if the cancer has metastasized before I operate on your shoulder,” he said. He scheduled a battery of tests over the next six weeks, followed immediately by the shoulder operation.

The surgeon’s diagnosis frightened me. “Could this be fatal?” I asked him.

“Try not to worry,” he said. “We’re very good at what we do.”

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

I got lost driving home. I pulled to the curb, cut the ignition, and took deep breaths.

A couple years earlier, a nice gray-haired lady driving a black Escalade hit me and my grocery cart as I walked from a Ralph’s store through a crosswalk. I wasn’t hurt, but she fell apart, sobbing hysterically. It took her a long time to calm down enough to tell me she’d just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. I helped her park her Escalade and called her husband.

The Grim Reaper blinded the nice lady that day. Now he squatted on the hood of my truck. I punched my home address into Google Maps and followed the voice commands, crawling along at a turtle-pace in the slow lane.

When I got home, I told Cindy. Positive and supportive as always, she didn’t flinch. “You’re strong! If they find something, you’ll beat it!” My son and daughters said the same. So did my good friend and horseback-riding instructor, Janet. And my riding buddy, Alecia.

Everyone was confident except me. That night in bed in the dark trapped inside my head with the boogeyman, I was certain the cancer had metastasized. I catalogued all the recent symptoms I’d ignored that might be cancer related. Those hard cramps last week, stomach cancer; my aching joints, bone cancer; occasional headaches, brain cancer; severe chest congestion, lung cancer. I imagined various scenes with the surgeon delivering different deadly diagnoses.

Show some courage, I told myself. You’re 77. You’ve lived a long full life. Cancer cut Paul down in his prime, but he faced death bravely. Go out proud and brave, like he did.

I don’t want to go out! I love my life. I want to stay with Cindy, my kids and grandkids, the horses, P.D., my friends. I don’t want to die!

Get a grip. You’re not going to die. You don’t know anything yet. You don’t even know if the cancer has spread.

Yeah, well, I know something is growing inside me right now that could kill me.

And so it went. On and on. All night long.

At dawn, I drove to the barn and went to Lily’s stall. An Azteca gray mare, she has equine melanoma. There is no cure, but it isn’t always fatal. She may live out her life with the cancer or it may kill her, and there’s nothing I can do to influence the outcome. (See Lily’s Song for more about her.)

I groomed her, then stood beside her, looking into her soulful eyes. I placed my forehead against her neck and put my arm over her back. Even if they love you, most horses pull away when you hold them close for too long. That morning, Lily stood still for me. I don’t know if she knew, but it felt like she did.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

In the 1970’s, I taught English Literature to high school seniors. One of them later became the top intellectual property attorney in the nation. Now in retirement, he’d been diagnosed with cancer and was undergoing treatment. “I’m scared crazy,” I wrote to him.

“This ‘not knowing’ stage that you are in might well be the hardest part of the process,” he wrote back. “I hope and pray the cancer has not spread. That is the hope and prayer of all in our club. But if it has spread, to a small or large degree, you are smart and capable and surrounded by a great medical team and family, and you will deal with it as best as you can. That’s all we can do.” His steady guidance through the coming weeks calmed me down and gave me hope.

Meanwhile, my cancer tests went forward. Most of them were familiar to me from previous ailments and some seemed designed only to determine if I was healthy enough to survive surgery, but I agonized over each one, convinced it would discover more cancer. Thankfully, my anxieties went unrealized. One by one, the results came in negative.

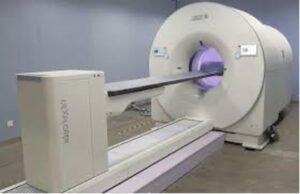

The last test, the big mother of them all, the one I feared most, the PET CT Whole Body scan, came at the end of the six weeks. My daughter, Devon, drove me to COH’s radiology department. They injected me with radioactive fluid, placed me on a gurney, and slowly slid me through a giant donut, capturing internal images of my entire body, starting at my feet and moving up to the top of my head. If there were cancerous tumors inside me, the donut would find them. The technician said the results would come back in three days, just before the shoulder operation.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

I was still frightened by my dream when I got to the barn at dawn. Lily was skittish and flighty, but she calmed down when I stroked her neck and rubbed her ears. I did, too. I stayed with her a long time that morning.

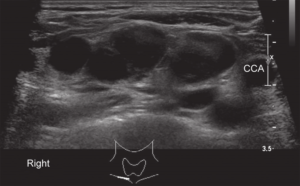

On the day of my operation, they stretched me out on a bed in the nuclear medicine room and injected radioactive fluid into my shoulder to track blood flow to the nearest lymph nodes. For the cancer to spread from my shoulder it would first infect “sentinel” nodes that would carry the cancer elsewhere. The procedure would identify any bad ones the surgeon would need to remove. The technicians worked on me for two hours, then wheeled me down to pre-op.

The surgeon came in. “The Whole Body scan was good,” he said. “It found no cancer anywhere other than in your shoulder.”

Sitting by my bed, my son, Josh, pumped his fist. “Yes!”

If I hadn’t been exhausted, I would have jumped up and cheered.

Now, it all came down to the shoulder surgery and the potentially infected lymph nodes. They rolled me into the operating room, and the anesthesiologist knocked me out.

I awoke in the recovery room with a bandage on my shoulder covering an incision three inches long. I was telling the nurse about Lily when the surgeon came in, smiling. “I got all the cancer. We didn’t take any lymph nodes. They all looked good.”

That was the night of September 9. I’d gotten the best possible results on all the tests; the surgery was successful; and my lymph nodes appeared to be clear. I was elated.

I thought cancer was done with me, but in the post-op meeting, I learned that membership in the cancer club is like the Eagles’ Hotel California. You can check out, but you can never leave.

Cancer is resilient. It might be hiding in clusters of cells too small for the tests to detect, waiting to blossom into new tumors, or it might sprout inexplicably again in a new location, like it did in my shoulder. “We will observe you,” the surgeon said. He ordered a round of tests for next February, including another PET CT Whole Body scan. After that, he plans to slide me through the big donut every six months. If the cancer comes back, the surgeon will find it early to give us the best chance of beating it.

Cancer’s Hotel California is a big place with many rooms. Cancer victims pay a dear price for most of them: chemotherapy, radiation, ablation, immunotherapy, stem cell transplants, hormone therapy, bone marrow transplants. Not me. I got off easy, at least for now. I got the best room in the building, and it cost me almost nothing. No real pain. No significant sacrifice. Just six weeks of worry and the prospect of periodic tests going forward.

Although my little skirmish didn’t require the colossal strength, boundless stamina, and lion-hearted courage so many cancer patients bring to their grueling battles against the disease, it scared me enough to change me forever. It gave me a priceless gift: The realization that each day of my life is precious. Of course, I knew that all along. We all know it. But I know it in a different way now. I know it deep down inside, and I never forget, even for a moment.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.

On a stormy night in June, 1975, I steered our mustard-colored Pinto station wagon down the interstate’s off-ramp and headed toward an oval-shaped sign atop two telephone poles. Neon letters shining through streaks of rain. “Dudley’s Motel,” the second “d” flickering.

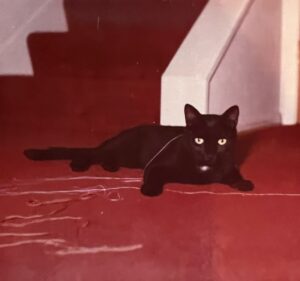

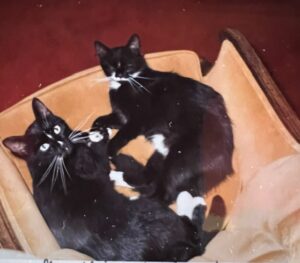

On a stormy night in June, 1975, I steered our mustard-colored Pinto station wagon down the interstate’s off-ramp and headed toward an oval-shaped sign atop two telephone poles. Neon letters shining through streaks of rain. “Dudley’s Motel,” the second “d” flickering. The silence of the cats awoke Cindy. She sat up straight, rubbed her eyes, and looked back at the cage. “They okay?”

The silence of the cats awoke Cindy. She sat up straight, rubbed her eyes, and looked back at the cage. “They okay?” I got out of the car and went inside. An old woman with thinning gray hair sat behind a desk watching The Tonight Show on a little black-and-white Zenith.

I got out of the car and went inside. An old woman with thinning gray hair sat behind a desk watching The Tonight Show on a little black-and-white Zenith. I drove the Pinto around to the back. Cindy went inside and cased the room. We learned a hard lesson the night Lazy Bones slipped into a hole around the plumbing under a motel room’s bathroom sink and climbed up inside the wall to the floor above. Took us an hour and a can of tuna to lure him back down.

I drove the Pinto around to the back. Cindy went inside and cased the room. We learned a hard lesson the night Lazy Bones slipped into a hole around the plumbing under a motel room’s bathroom sink and climbed up inside the wall to the floor above. Took us an hour and a can of tuna to lure him back down.

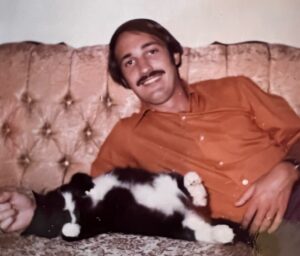

We all would have lived happily ever after in the country if I hadn’t done better than we expected in law school. National law firms opened their doors to us. At the end of a dizzying recruiting process, I accepted an offer to join Latham and Watkins in Los Angeles.

We all would have lived happily ever after in the country if I hadn’t done better than we expected in law school. National law firms opened their doors to us. At the end of a dizzying recruiting process, I accepted an offer to join Latham and Watkins in Los Angeles. I called the Latham attorney assigned to help me with our transition. Blithering away nervously, I tried to explain how we got stuck with five cats and asked if he could find a place to stash them while we searched for an apartment in LA. A really good guy with a sense of humor, he put me in touch with Ida’s Cat Kennel, and I made reservations for our herd.

I called the Latham attorney assigned to help me with our transition. Blithering away nervously, I tried to explain how we got stuck with five cats and asked if he could find a place to stash them while we searched for an apartment in LA. A really good guy with a sense of humor, he put me in touch with Ida’s Cat Kennel, and I made reservations for our herd. Tranquilizers didn’t help, so I opted for compulsory confinement. I built a cage out of two-by-fours and chicken wire big enough to hold all five of them but small enough to fit in the Pinto.

Tranquilizers didn’t help, so I opted for compulsory confinement. I built a cage out of two-by-fours and chicken wire big enough to hold all five of them but small enough to fit in the Pinto.

We turned the cats loose in Ida’s backyard and drove to Beverly Hills to meet Tanya, the realtor Latham hired to show us rental properties. In her late forties, tall and slim with shoulder-length brown hair, she was professional and cheerful. Over the next several days she showed us a series of attractive apartments. None of the landlords allowed pets. I told them all the truth. They all turned us down.

We turned the cats loose in Ida’s backyard and drove to Beverly Hills to meet Tanya, the realtor Latham hired to show us rental properties. In her late forties, tall and slim with shoulder-length brown hair, she was professional and cheerful. Over the next several days she showed us a series of attractive apartments. None of the landlords allowed pets. I told them all the truth. They all turned us down.

Two weeks later, I ran into the manager outside our apartment door as I came home from work. I froze. Vigoro sat in our living room window facing the courtyard, staring at him with her big yellow eyes.

Two weeks later, I ran into the manager outside our apartment door as I came home from work. I froze. Vigoro sat in our living room window facing the courtyard, staring at him with her big yellow eyes.

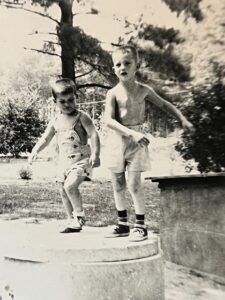

Donald and I walked through Maupin’s apple orchard at noon on a hot sunny day in 1963.

Donald and I walked through Maupin’s apple orchard at noon on a hot sunny day in 1963.

My family had moved to White Hall, Virginia, a couple years earlier. Country boys had taught me a few tricks. One of them was hand-fishing.

My family had moved to White Hall, Virginia, a couple years earlier. Country boys had taught me a few tricks. One of them was hand-fishing. I strung him along for about an hour before I clued him in. He was a good sport, and we laughed about it.

I strung him along for about an hour before I clued him in. He was a good sport, and we laughed about it.