Stay With Me

At dusk in December, I ride Wilson along the base of a steep mountain. We’ve slowed to a walk, but he’s struggling, his breath coming in short bursts, vapor jetting from his nostrils.

At dusk in December, I ride Wilson along the base of a steep mountain. We’ve slowed to a walk, but he’s struggling, his breath coming in short bursts, vapor jetting from his nostrils.

Zoey walks stiff-legged on the ground beside us. She looks up at me, her eyes watery and tired. Unable to go on, she sits down to rest.

I rein Wilson to a stop and dismount. He lowers his head, breathing hard. I stroke his neck and rub the star on his forehead with the palm of my hand.

I call Zoey. She comes to me and stands at my knee, her legs trembling. I kneel, pat her head, and scratch her ears.

A cold shadow falls over us as the sun goes down behind the mountain. I stand and lead Wilson and Zoey through a grove of live oaks, their branches clawing at an indigo sky, giant bony fingers clinging to the dying light. We emerge from the trees into an open field where scattered desert flowers still bloom, little islands of gold, burgundy, and russet in a sea of gray brush.

A cold shadow falls over us as the sun goes down behind the mountain. I stand and lead Wilson and Zoey through a grove of live oaks, their branches clawing at an indigo sky, giant bony fingers clinging to the dying light. We emerge from the trees into an open field where scattered desert flowers still bloom, little islands of gold, burgundy, and russet in a sea of gray brush.

We walk along a well-worn trail. Wilson and Zoey fall behind. I stop and look back. The night is coming on. “Don’t give up. Stay with me.” They try to quicken their pace, but they’re old and slow. A curtain of darkness slides across the valley toward them, and I can’t hold it back.

I awake and sit up on the edge of the bed, still inside my dream. It takes me a while to shake it off. I wipe my eyes and stare out the window. First light. Another day. “There’s still time,” I say, hoping it’s true.

I bought Wilson on the cheap five years ago. He came with no pedigree or papers. The seller said he was 12, but the vet thinks he’s well into his 20’s now.

He’s a good horse. He tries hard to do everything we ask of him. Last year arthritis ate into his spine, and we took his saddle off for good. See Riding Wilson for the whole story.

He’s a good horse. He tries hard to do everything we ask of him. Last year arthritis ate into his spine, and we took his saddle off for good. See Riding Wilson for the whole story.

On a riderless outing a few months ago, he hurt himself trying to dash up a hill. Afterwards, he walked with a sidewinding gait, his back legs unsteady. The vet prescribed steroid pills to reduce inflammation. “The time will come when I can’t help him anymore,” he said. He told me to move Wilson into the barn’s front stall so the hauler’s winch could reach him when that day arrives.

“I’ll move him,” I said, “but I want to buy the old boy as much time as I can.”

I mixed the medicine into Wilson’s feed daily. The sidewinding walk didn’t go away, but it got better. Janet, my horse trainer and good friend, put him on Equine Senior Feed to help him hold his weight. Always a homebody, he seemed content in his corral.

Then something went wrong with his front legs. He flinched in pain with every step. He stared vacantly into the distance with rheumy eyes. He didn’t respond to my voice or touch.

Then something went wrong with his front legs. He flinched in pain with every step. He stared vacantly into the distance with rheumy eyes. He didn’t respond to my voice or touch.

The vet thought he had laminitis, a disease where the coffin bone inside the hoof pulls away from the hoof wall. It’s extremely painful, and there’s no cure. He scheduled a visit for the next day to x–ray Wilson’s hooves.

Visions of the hauler and his winch kept me up all night.

At dawn, I went to the barn to feed him. He stood in the corral at the bottom of the hill. Normally, he would run up to the barn to be fed, but that morning he stood still as a statue, rooted to the ground. I called him. He didn’t move. I haltered him and pulled him up the hill. Every step was torture for him. Twice he almost fell. Fighting back tears, I tried to come to terms with the heartbreaking decision that would be best for him.

That afternoon I crouched beside the vet in front of a portable x–ray machine staring at images of the inside of Wilson’s front hooves. “They’re worn down,” the vet said. “Too short and too shallow. It’s like he’s walking on broken glass with bare feet.” Despite that, the vet was encouraged. “We caught this early. There’s a good chance we can treat it.”

That afternoon I crouched beside the vet in front of a portable x–ray machine staring at images of the inside of Wilson’s front hooves. “They’re worn down,” the vet said. “Too short and too shallow. It’s like he’s walking on broken glass with bare feet.” Despite that, the vet was encouraged. “We caught this early. There’s a good chance we can treat it.”

The vet power-drilled metal screws into Wilson’s front hooves to attach thick wooden horseshoe-blocks to them, then wrapped them in plaster-cast tape. When he was done, I led Wilson back to his stall. Wearing Dutch clogs, his first steps were awkward, but his gait soon smoothed out. His personality came back. He nudged my shoulder for pets and strokes, and when I came to feed him, he ran across the corral, kicking and bucking like a young horse.

The vet will take off the clogs after six weeks. It’s not a sure thing his hooves will heal by then, but the early indications are positive. It looks like Wilson will outrun the darkness for a while longer.

Meanwhile, Zoey did not fare as well. We feared she would pass away in September with a kidney ailment, but she recovered. See Zoey’s Song for that story.

Meanwhile, Zoey did not fare as well. We feared she would pass away in September with a kidney ailment, but she recovered. See Zoey’s Song for that story.

In November, our fears returned when she fell and couldn’t get up, but when the vet gave her shots for arthritis, she rebounded again.

Then, on New Year’s Day, she suffered a grand mal seizure. I can’t bear to describe it here other than to say it was horrible and heart-wrenching to watch. While I searched frantically for a vet who would help her on the holiday, she had two more seizures, shorter and milder than the first. I finally found an emergency facility in Culver City, and my son-in-law helped me take her there. It’s an hour’s drive, and I thought she might die in the car on the way, but she made it.

The emergency vet stabilized her with anti-seizure medication. An ultrasound revealed an enlarged heart with an imminent risk of a fatal heart attack. The next day our regular vet put her on heart medication.

The emergency vet stabilized her with anti-seizure medication. An ultrasound revealed an enlarged heart with an imminent risk of a fatal heart attack. The next day our regular vet put her on heart medication.

Each morning and evening I mixed eight pills into her food, and every four days I gave her the arthritis shots. I was worried about pumping so much medication into her, but it worked, and miraculously she bounced back yet again. Her arthritic pain eased; the seizures went away; and the heart pills seemed to make her stronger. She woke up every day wagging her tail. She took two long daily walks morning and afternoon, and she was active and alert.

Six weeks later, she had two mild, short seizures two days apart. Both times she recovered quickly and acted as though nothing had happened. We increased her anti-seizure medication.

Six weeks later, she had two mild, short seizures two days apart. Both times she recovered quickly and acted as though nothing had happened. We increased her anti-seizure medication.

On Friday, February 17, at dawn, she and I went out to get the paper. Figuring she was too old and infirm to run off, I didn’t leash her. Meandering around the front yard, she suddenly put her nose in the air, and the hair on her neck stood up. I was too far away to restrain her when I saw the coyote.

Baying and sprinting after him like a young dog, she chased him up our neighbor’s long, steep driveway while I ran a distant third behind them. When I finally caught up to Zoey at the top of the hill, the coyote had fled. Zoey turned around and trotted back down the hill, looking energized and proud about protecting her turf.

I’m glad we got to share that last big chase. She looked so brave and strong.

That afternoon at four o’clock I found her in my home office. She’d rolled over on her side and passed away peacefully.

That afternoon at four o’clock I found her in my home office. She’d rolled over on her side and passed away peacefully.

If you’re blessed, once in your life you form a special bond with a dog that’s different from all the other dogs you loved. You know what she thinks and feels, and she has that same sense of you. It’s a magical connection, deep, warm, loving, soulful.

I’d like to believe it can’t be broken, even by death, but I don’t know if that’s true. All I know is I still feel it, and I always will.

A gray mist shrouded a sea of bobbing heads crawling past the Mile 23 sign. A sinewy ancient man wearing plaid Bermuda shorts, black nylon socks, and orange tennis shoes clumped along beside me. His iron-gray hair cinched in a ponytail, his leather face lined with a thousand creases, his every breath whistling like a tea kettle, he rasped in a singsong, sandpaper voice, “Run for the money, wheeze-wheeze, run for the gold, wheeze-wheeze, run till you’re o–o–o–old, wheeze-wheeze.” He flashed a taunting grin at me, picked up his pace, and disappeared into the crowd up ahead.

A gray mist shrouded a sea of bobbing heads crawling past the Mile 23 sign. A sinewy ancient man wearing plaid Bermuda shorts, black nylon socks, and orange tennis shoes clumped along beside me. His iron-gray hair cinched in a ponytail, his leather face lined with a thousand creases, his every breath whistling like a tea kettle, he rasped in a singsong, sandpaper voice, “Run for the money, wheeze-wheeze, run for the gold, wheeze-wheeze, run till you’re o–o–o–old, wheeze-wheeze.” He flashed a taunting grin at me, picked up his pace, and disappeared into the crowd up ahead. This death march went down on March 5, 2000. I was 52. Thirty years earlier, I’d taken up running in college to relieve stress and kept it up throughout my working life. I wasn’t fast, but I could run a long way at a slow pace. Somewhere along the line, the dream of completing a marathon got ahold of me, but my work schedule couldn’t accommodate the rigorous training required. Suddenly faced with an abundance of free time when I left Safeway in January, I signed up for the LA Marathon.

This death march went down on March 5, 2000. I was 52. Thirty years earlier, I’d taken up running in college to relieve stress and kept it up throughout my working life. I wasn’t fast, but I could run a long way at a slow pace. Somewhere along the line, the dream of completing a marathon got ahold of me, but my work schedule couldn’t accommodate the rigorous training required. Suddenly faced with an abundance of free time when I left Safeway in January, I signed up for the LA Marathon. On March 5 at 7:30 am, 20,000 runners gathered in the starting pen on Figueroa Street in a torrential downpour. I stood at the back of the pack, peering through the monsoon at Mayor Riordan, perched on an elevated platform at the starting line. Laughing maniacally, his helmet of thinning white hair sopping wet, he shouted into a bull horn, “Welcome to sunny California” and fired the starting gun.

On March 5 at 7:30 am, 20,000 runners gathered in the starting pen on Figueroa Street in a torrential downpour. I stood at the back of the pack, peering through the monsoon at Mayor Riordan, perched on an elevated platform at the starting line. Laughing maniacally, his helmet of thinning white hair sopping wet, he shouted into a bull horn, “Welcome to sunny California” and fired the starting gun. As we ran through downtown, people clad in rain gear lined the streets. “Keep going! You’re doing great!” Volunteers at the USC Coliseum handed us cups of water and shouted encouragement. Farther on, someone bugled a cavalry charge from a second-floor apartment window. At Mile 8, lightning struck, and thunder boomed. We all gasped, then cheered, and ran on.

As we ran through downtown, people clad in rain gear lined the streets. “Keep going! You’re doing great!” Volunteers at the USC Coliseum handed us cups of water and shouted encouragement. Farther on, someone bugled a cavalry charge from a second-floor apartment window. At Mile 8, lightning struck, and thunder boomed. We all gasped, then cheered, and ran on. Then the terrain leveled off. I started to feel strange. Hollowed out. Numb. In the mid-Wilshire District, the course took a sharp turn, but my rubbery legs kept going straight. To force my strides to make a wide arc to the left, I had to lean sideways at a thirty-degree angle like a guy on a motorcycle.

Then the terrain leveled off. I started to feel strange. Hollowed out. Numb. In the mid-Wilshire District, the course took a sharp turn, but my rubbery legs kept going straight. To force my strides to make a wide arc to the left, I had to lean sideways at a thirty-degree angle like a guy on a motorcycle. All the people I had passed in my speed-run since the halfway mark, plus thousands more, overtook me, including Zombie-Man. I couldn’t keep up with any of them. Each torturous step required a supreme act of will. I slowed to a walk, then stopped and leaned over, propping my hands on my knees. I thought I was done.

All the people I had passed in my speed-run since the halfway mark, plus thousands more, overtook me, including Zombie-Man. I couldn’t keep up with any of them. Each torturous step required a supreme act of will. I slowed to a walk, then stopped and leaned over, propping my hands on my knees. I thought I was done. Riveting my eyes to those words, I leaned forward and fell into a painful, staggering jog. Through Miles 24, 25, and 26, when the t–shirt’s letters grew smaller, I’d reach way down and somehow find the strength to reel them in. They’d fade again, and I’d bring them back. Again and again, they pulled me forward.

Riveting my eyes to those words, I leaned forward and fell into a painful, staggering jog. Through Miles 24, 25, and 26, when the t–shirt’s letters grew smaller, I’d reach way down and somehow find the strength to reel them in. They’d fade again, and I’d bring them back. Again and again, they pulled me forward. A digital timer hung over the finish line. Big red numbers, 4:59:53 and ticking.

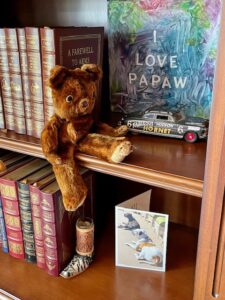

A digital timer hung over the finish line. Big red numbers, 4:59:53 and ticking. Last week I was rummaging around in a closet where we keep toys for our grandkids’ visits when I found a brown teddy bear at the bottom of a cardboard box. I was surprised to find him there. He and I go back a long way, but I hadn’t seen him in years. I carried him to the bed, sat down, and looked him over. Memories flooded over me.

Last week I was rummaging around in a closet where we keep toys for our grandkids’ visits when I found a brown teddy bear at the bottom of a cardboard box. I was surprised to find him there. He and I go back a long way, but I hadn’t seen him in years. I carried him to the bed, sat down, and looked him over. Memories flooded over me.

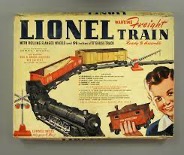

I was a little boy back then, too excited to care how my parents felt about giving me those gifts, but I know now, from my own feelings about my son’s first Christmas, how much that morning meant to them. I was their first child, and at that point still their only child, and that was the first Christmas I was old enough to understand the magic of Santa Claus. Their reward for their sacrifice was my unbridled joy, and to them it was priceless.

I was a little boy back then, too excited to care how my parents felt about giving me those gifts, but I know now, from my own feelings about my son’s first Christmas, how much that morning meant to them. I was their first child, and at that point still their only child, and that was the first Christmas I was old enough to understand the magic of Santa Claus. Their reward for their sacrifice was my unbridled joy, and to them it was priceless. When Jackie Paper was a little boy, he played with Puff the magic dragon in the imaginary wonderland of Honah Lee. A dragon lives forever. Not so with little boys. Jackie grew up and came to Honah Lee to play with Puff no more.

When Jackie Paper was a little boy, he played with Puff the magic dragon in the imaginary wonderland of Honah Lee. A dragon lives forever. Not so with little boys. Jackie grew up and came to Honah Lee to play with Puff no more. As I sat on the bed staring at him, the many happy Christmases of my youth came back to me, including my last Christmas at home with Mom, Dad, and my brothers. I was twenty, home on holiday break from UVA. Dad had been the preacher at Mount Moriah Methodist Church in White Hall, Virginia, for six years. Every year the church gave baskets of food and boxes of toys to poor families on Christmas Eve. I’d never joined the church members on the trips to deliver gifts. I always had a date or a party to attend, something fun to do, but that year Dad insisted I go along.

As I sat on the bed staring at him, the many happy Christmases of my youth came back to me, including my last Christmas at home with Mom, Dad, and my brothers. I was twenty, home on holiday break from UVA. Dad had been the preacher at Mount Moriah Methodist Church in White Hall, Virginia, for six years. Every year the church gave baskets of food and boxes of toys to poor families on Christmas Eve. I’d never joined the church members on the trips to deliver gifts. I always had a date or a party to attend, something fun to do, but that year Dad insisted I go along.  The shack’s door opened. Johnny Sipe stood in the doorway. In his early twenties, short and heavyset, with dark sunken eyes, he did his best to maintain a tight, twitchy smile as we sang the carol. His bone-thin pale girlish wife stood behind him, peeking timidly over his shoulder. A few verses into Silent Night, she retreated inside the shack and sat on the edge of a bed. In the flickering candlelight, I could barely see two little faces staring at us, the bed covers pulled up to their chins.

The shack’s door opened. Johnny Sipe stood in the doorway. In his early twenties, short and heavyset, with dark sunken eyes, he did his best to maintain a tight, twitchy smile as we sang the carol. His bone-thin pale girlish wife stood behind him, peeking timidly over his shoulder. A few verses into Silent Night, she retreated inside the shack and sat on the edge of a bed. In the flickering candlelight, I could barely see two little faces staring at us, the bed covers pulled up to their chins.  Most everything Cindy and I tried worked out for us. Some of that was because of effort and talent; some of it was because someone helped us climb out of a hole; and some of it was because each time we pushed all the chips into the middle of the table and bet against the odds, we won.

Most everything Cindy and I tried worked out for us. Some of that was because of effort and talent; some of it was because someone helped us climb out of a hole; and some of it was because each time we pushed all the chips into the middle of the table and bet against the odds, we won.