Riding Wilson

Last month, when the farrier lifted Wilson’s right back hoof to shoe him, the twenty-year-old thoroughbred lost his balance and almost fell. Having seen this before in older horses, the farrier ran his hand along Wilson’s neck and back, and as he expected, he flinched and nipped at him.

We called the vet. He stood beside Wilson’s hindquarters and pulled his tail toward him. Wilson swayed, then stumbled. “The normal reaction,” the vet said, “is for the horse to brace against the tugging force and hold his position. Wilson can’t do that because he’s not sure where his back legs are.”

Arthritis in his neck had damaged nerves running down his spine to his legs. Arthritis is incurable and relentlessly degenerative. “All we can do,” the vet said, “is slow down the skeletal deterioration.”

He prescribed prednisolone. “If the drug works,” the vet said, “Wilson should be able to carry a rider bareback or with a swayback cushion under the saddle for a few more years.”

The next morning, I dissolved 400 milligrams of the drug in water, mixed it with oats and molasses, and spread it over Wilson’s alfalfa. Later in the day, Janet, my trainer and good friend, riding her horse, Jesse, ponied Wilson while I followed on Marge. Wilson struggled, especially on the downhill slopes. When we finished up, he was sweating; his head was down; and he was drooling. Even a riderless walk had broken him down.

That was a watershed moment for me. I knew then that I would never again allow anyone, including me, to climb on Wilson’s back. Even if the drug worked, I wouldn’t take the chance of inflicting more pain on him.

It’s the right decision, but I’ll miss my rides with Wilson.

I first saw him almost four years ago on a home-made sales video. A young woman lunged a handsome, glossy bay in a dirt corral in Bakersfield, then rode him on a bareback pad over a dusty road. Doing his best to ignore a trio of mutts scurrying around his feet, Wilson followed the young woman’s cues, carefully backing up, standing still, and moving forward, to enable her to open a gate without dismounting.

I liked his demeanor. The way he held his head and the look on his face gave me the sense he was a good soul, trying hard to do his job well. The asking price was low and the young woman agreed to trailer him to Hidden Hills without charge, so I bought him.

She delivered him on a cool, clear February evening, and Janet and I walked him up the hill on Clear Valley Road toward my barn. A big, tall horse, a little under sixteen hands (about five feet four inches from the ground to his withers, the spot where his neck joins his back), his dark brown neck and head framed by a peach sunset, his black mane and forelock riffling in a light breeze, his head held high, his eyes alert, he looked around anxiously at the residential homes and manicured lawns.

When you buy a horse like Wilson, with no papers or pedigree, you know nothing about his history, what he’s been through, or how he’s been treated. More than likely, Wilson passed through many owners’ hands, some who were good to him and others who were cruel. Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, wrote that such a horse’s life is like “twenty years in foster care, or in and out of prison, while at the same time changing schools over and over and discovering … that what you learned at the old school hasn’t much application at the new one.”

That passage ran through my mind as I watched Wilson prance nervously up the street. Earlier that afternoon, he stood on a drought-parched farm where everything was familiar to him. Without warning, the young woman came along, put a halter on him, and loaded him into a small, cramped tin box. For the next two and a half hours, he jounced around inside the metallic stall, as it rocked and swayed over freeways at seventy miles per hour, speeding him away from everything he’d ever known. When the trailer finally stopped, the young woman clanged open the rear door, backed him down a ramp, and handed his lead line to people he’d never met in a place where all the sights, sounds, and scents were completely foreign to him. Headed up the hill toward my barn that evening, he had to be lost and frightened by the sudden, radical change we’d forced upon him, and yet I sensed he was trying hard to adjust to this new world.

We led him into his stall. He walked around apprehensively, checking out the gray stucco walls and the wood shavings on the floor. He drank from the water bucket, then looked out the Dutch stall-door, taking in the street below, the valley, and the opposite ridge. We gave him orchard grass and alfalfa, and he attacked it like he hadn’t been fed for days. When I left him an hour later, he’d calmed down a little and seemed to be settling in.

His name on the bill of sale was Chippy. It didn’t fit. I’m not sure why, but the name Wilson came to mind when I was with him that night in the barn. I went with it, and it took hold.

A few days after Wilson’s arrival, we put him in the corral with his stablemate, Margarine, a little sorrel alpha mare. She hates most other horses. She tolerated Wilson for about an hour before attacking him. I ran a fence down the middle of the corral to keep the peace and called the vet to tend to Wilson’s bruises. For a more detailed account of their dust-up, see Animal Pharm.

The vet said Wilson was physically sound, but older than we thought. The young woman said he was twelve. The vet said he was sixteen or older. I didn’t care. I wanted a trail horse who would be good with my grandkids, and he fit the bill.

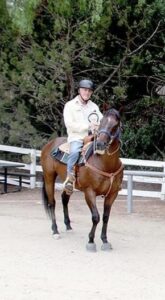

Janet spent the next few weeks training him, and he adapted to the neighborhood streets and trails quickly. I first rode him that spring. He wasn’t a comfortable ride. His walking gait was irregular, choppy, and bumpy, and his trot was like sitting on a jackhammer, but I liked riding him anyway.

Horseback riding presents a thrilling paradox. When you climb in the saddle, you must take a measure of control over your mount, but sitting on a twelve-hundred-pound animal, you give up a lot of control at the same time. Wilson’s tall frame and big barrel encase extraordinary power, and his speed lives up to his breed. My awareness of his power and speed made riding him exciting each time we went out. He turned out to be a gentle giant, though. He was always a safe ride except once when he reared for reasons beyond his control. See For the Love of Horses for a description of that incident.

Janet determined early on that Wilson was “cold backed” (sensitive to weight on his back until he was warmed up). We lunged him for a long time before each ride to compensate for that, but the steep downhills still seemed to strain his back, so we rode him on flatter trails.

Looking back on it now, I feel guilty about some of those rides. He must have been suffering, especially during the more recent outings, but he did whatever I asked of him, always giving his best effort, never balking or faltering.

About five days into Wilson’s treatment with prednisolone, the drug worked its magic. When I arrived at the barn that morning to feed him, he ran up the hill to his stall like a young horse. When we ponied him that day, the pain seemed to be gone, but I haven’t changed my mind. I know too much about arthritis. It crippled my knees until they were replaced, and I still have it in my fingers. Medication eases the pain for a while, but it always returns. Wilson’s been through enough. His riding days are over.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.

I’m told that some owners would dispose of an older horse in Wilson’s condition, dump him on a rescue organization, or send him to a kill-pen. I can’t do that. Wilson did his job well for as long as he could. Now I’ll do mine. I’ll keep him healthy, happy, and safe for the rest of his life.

Post Script: “Take care of your horses and treasure them.” Jane Smiley

Twenty years old, she’d worked as a secretary for Cambridge, Inc., a small mortgage brokerage firm, for only a month when she claimed the CEO sexually assaulted her. He insisted he never touched her.

Twenty years old, she’d worked as a secretary for Cambridge, Inc., a small mortgage brokerage firm, for only a month when she claimed the CEO sexually assaulted her. He insisted he never touched her. “My office is across the hall,” Margaret said. “I saw her come out and run down the hall. She was sobbing hysterically. I found her in the women’s restroom. It took her a long time to calm down enough to tell me her version of what happened. She was so upset I sent her home for the day.”

“My office is across the hall,” Margaret said. “I saw her come out and run down the hall. She was sobbing hysterically. I found her in the women’s restroom. It took her a long time to calm down enough to tell me her version of what happened. She was so upset I sent her home for the day.” “She’s a good liar,” I said. “In the few seconds it took her to reach your office door, she burst into tears and kept it up until Margaret sent her home.”

“She’s a good liar,” I said. “In the few seconds it took her to reach your office door, she burst into tears and kept it up until Margaret sent her home.”

I argued long and hard, but Ted wouldn’t budge, which put me in a tight spot. The canons of ethics prohibit a lawyer from presenting false evidence to the court, so I couldn’t knowingly allow Ted to lie under oath. But the rules also prohibited my disclosure of his confession to anyone, including the court. Under California law, there was only one way to protect both conflicting interests. I withdrew from the case without telling anyone what Ted had told me, and he hired a different firm to defend the lawsuit.

I argued long and hard, but Ted wouldn’t budge, which put me in a tight spot. The canons of ethics prohibit a lawyer from presenting false evidence to the court, so I couldn’t knowingly allow Ted to lie under oath. But the rules also prohibited my disclosure of his confession to anyone, including the court. Under California law, there was only one way to protect both conflicting interests. I withdrew from the case without telling anyone what Ted had told me, and he hired a different firm to defend the lawsuit.