Friendship First

In 1987, my son played baseball in Beijing. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invited the U.S. to field Little League teams to compete with Chinese kids. Two coaches put together a team from California. My son made the roster, and I volunteered to go along as a parent-chaperone.

In 1987, my son played baseball in Beijing. The People’s Republic of China (PRC) invited the U.S. to field Little League teams to compete with Chinese kids. Two coaches put together a team from California. My son made the roster, and I volunteered to go along as a parent-chaperone.

When the Communist revolutionaries took control of China in 1949, Mao Zedong closed the country to outside influences. It remained closed until the 1970’s, when the PRC began to open China’s doors gradually. One of its programs to promote foreign exchange was “sports diplomacy.” The 1987 Beijing baseball tournament was part of that ongoing effort.

Mao banned baseball as an evil Western influence and the PRC had resurrected the sport only a few years before the tournament, so we expected the Chinese teams to be green and unskilled. We were wrong. They were stacked with talented, well-coached players. China’s A Team won the tournament; its B Team was the runner-up.

While the PRC was proud of its baseball teams, the stated goal of its sports diplomacy program was “friendship first, competition second.” Its primary interest in sponsoring the games was to impress its U.S. visitors with the virtues of China. To that aim, our hosts gave us Rolls Royce tours of The Great Wall, The Forbidden City, The Terra Cotta Warriors of Xian, and many other sights.

We were instant celebrities everywhere we went. Although China had been partially open for a decade, Western tourists were still a novelty in rural areas where gleeful crowds surrounded us, shook our hands, and took photographs with us.

Most of our experiences were wonderful. I was bowled over by the country’s rich culture, friendly people, and beautiful scenery, but a dark side of China also emerged.

My uneasiness began with our visit to a youth sports training complex. Our guide led us into an airplane-hangar-sized building filled with ping pong tables where kids from ages six to sixteen were all practicing the same serve, pounding the ball at high speed low across the net with spin. Again and again.

It was a sweltering day, and the building wasn’t air conditioned. I watched a little boy drenched in sweat, listening to his coach, adjusting his serve, hitting the ball, adjusting again, trying again. He was working hard.

I looked all across the room. I didn’t see any smiles.

We toured training areas for gymnastics, martial arts, and fencing. The story was always the same. Repetitive drills, focused effort, hard work.

Our guide said scouts selected children for each sport from all over the country and moved them to the complex where they trained to make national teams while living in dormitories onsite. In 1987, the children’s parents weren’t moved to Beijing with them and many hadn’t seen them for years. (The government later changed that policy to keep families together.)

The Chinese Little League players lived and trained in this facility. In 1980, the PRC had hired Bill Arce, a legendary Claremont College coach, to revive baseball in China. Arce conducted clinics and trained players in the Beijing complex. The Chinese A and B Teams were a product of those clinics. They were extraordinary ball players. Every swing of the bat was picture-perfect. Every pitch hit its mark. Every ball was fielded flawlessly. But like the ping pong kids, the Chinese Little Leaguers didn’t smile much.

On the way back to the hotel from the sports complex, our bus driver navigated through a sea of bicycles into a busy intersection. An oncoming bus, trying to gain the right-of-way, played chicken and gently tapped our bumper. Both drivers jumped out and got in each other’s faces. The police came and took the other driver away in handcuffs. I was surprised. The drivers had exchanged no blows, and the minor traffic accident didn’t seem to be a crime. Later I asked our translator, Zhou, what charges the driver would face. “Disturbing the social order,” he said. Zhou didn’t know, or wouldn’t say, what his punishment would be.

At dinner that night, I asked Zhou about daily life in China. He said Communist Party leaders decided where people lived. The Party had assigned Zhou a one-bedroom apartment where his parents, his brother’s family, and Zhou’s family all lived together. He was pleased, he said, that the Party had recently granted their request for an upgrade to a two-bedroom unit. The application had been pending for four years.

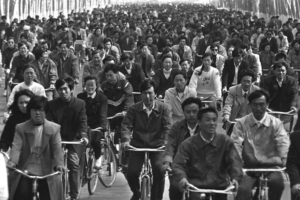

Zhou said the Chinese couldn’t travel out of their home area without the Party’s approval. He didn’t consider this a troublesome restriction because most people didn’t have a car. In 1987, the Party gave driver’s licenses and assigned vehicles only to those whose jobs required it. The masses traveled by bicycle.

Zhou told me the Party decided all job assignments. He had tested poorly, so the Party made him a security guard. Zhou had learned English in the 1960’s when it was the primary foreign language taught in Chinese schools. When the government opened the country, Zhou applied for a job transfer to Translator based on his proficiency in English, and the Party granted his request.

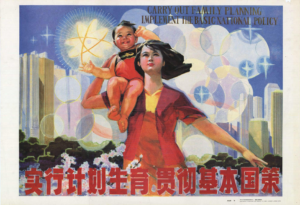

In 1979, the PRC instituted a policy that no couple could have more than one child unless the Party granted an exception, which was rare. When I asked Zhou if he agreed with the one-child policy, he couldn’t fathom the question. The idea of disagreeing with the government was foreign to him.

I didn’t sleep much that night.

Near the end of our trip, our hosts took us to Tianjin, a coastal port on the Bohai Sea, to play a local team. The Tianjin team wasn’t comprised of nationally selected players, who lived and breathed baseball. The game was close, but our team won.

After dinner, we took the boys outside to work off pent-up energy. Our guide and Zhou, who had always accompanied us wherever we went, weren’t in the dining room when we left. We only planned to walk around the block, so we didn’t wait for them to return.

In an alley behind the hotel, we measured off fifty yards and paired the kids to run sprints against each other. A small Chinese crowd gathered as the races started. The Chinese cheered the competitors, laughing and clapping. With every race, the crowd grew larger and louder.

After our coaches raced to a photo-finish, two young Chinese men motioned that they wanted to race each other. We cheered them on. A couple of Chinese kids raced next. Then a pair of older Chinese men.

The crowd grew to more than a hundred people. Chinese kids raced our kids. Chinese men raced our coaches and dads. We all yelled and screamed for the runners, slapping backs, jumping up and down, and laughing hysterically. It was great fun.

Until our guide and Zhou showed up with the police. Silence fell over the alley. The police dispersed the crowd, and we trudged back to the hotel.

Zhou explained that such spontaneous gatherings were not allowed. We had disturbed the social order.

We left China two days later. I didn’t realize how the trip had affected me until we got home. When our plane touched down in Los Angeles, an invisible weight seemed to lift from my shoulders.

I loved China, especially the Chinese people, but I wasn’t fond of the Party. I haven’t gone back to China since our trip. As long as the Party is in control, I don’t plan to return.

Post Script: Two years after we left Beijing, one million protesters demonstrated for democratic reforms in Tiananmen Square, which we had toured on our way to The Forbidden City. The Party met them with 300,000 troops. They fired on the crowd,

killing more than a thousand people. Ten thousand were arrested. Several dozen were executed.

Ten years after we left Beijing, the PRC took control of Hong Kong, previously a democracy. For the next twenty years Hong Kong citizens peacefully resisted PRC influence over daily life. On June 9 of this year, full-blown protests erupted about an extradition bill. The police responded with tear gas, rubber bullets, and arrests. The demonstrations metastasized. The dispute is ongoing. It will not end well.

Next Tuesday marks the 70thanniversary of the establishment of the PRC.