The Story Behind the Story: The Closing

The Closing was inspired in part by a death penalty appeal I worked on in the 90’s. This is what happened in People v. Marshall.

The Closing was inspired in part by a death penalty appeal I worked on in the 90’s. This is what happened in People v. Marshall.

In 1986, John and Hattie Foster awoke before dawn to a woman’s screams coming from an abandoned warehouse behind their apartment building in South Central LA. “Please stop! Please don’t! Please! Please!”

John told Hattie to call the police. He grabbed a machete he kept under his bed, went down to the street, and stood in front of the warehouse.

A man dressed in dirty clothes and smelling of liquor came out the front door. Foster confronted him. He denied being with a woman in the building, and Foster allowed him to walk away. He was never seen or heard from again.

A little later, Sammy Marshall came out of the warehouse. Foster stopped him and detained him until the police arrived.

Marshall told the police he’d been in the building but hadn’t done anything wrong. He had a cut on his hand and blood on his sweatshirt. In a pat-down search, the police found a knife. Marshall withdrew a piece of paper from his pocket and tried to toss it away. It was a grocery company’s letter to Sharon Rawls about a check-cashing card.

The officers discovered Sharon Rawls’s corpse in the warehouse, her pants pulled down around her ankles and a wad of cloth stuffed in her mouth. An autopsy later revealed the cause of death to be strangulation.

The police arrested Marshall and ran his criminal record. They found numerous felony convictions, including rape in 1975 and assaults in 1978 and 1981. They searched his room and found the bus pass of Durneal H. She told them he attacked her in March and dragged her toward the warehouse where Rawls was killed in April. She fought him off, dropping her bus pass in the struggle.

Marshall’s trial took place in 1988. The prosecution’s evidence included tests matching the bloodstain on Marshall’s sweatshirt to Rawls’s blood type (DNA analysis was not available then), expert testimony that semen in her vagina could have been Marshall’s semen, his possession of her grocery company letter, and Durneal H.’s testimony.

Marshall’s court-appointed attorney, Ron Slick, put on no evidence and called no witnesses.

The jury found Marshall guilty and recommended death. The judge followed the recommendation.

In California, direct appeal of a death sentence to the California Supreme Court is automatic. The defendant’s execution cannot go forward until the appeal is exhausted. In 1990, there were 350 inmates on California’s death row. About half of them were in death penalty limbo because they didn’t have lawyers.

Attorneys don’t line up around the block to take capital cases. They drag on for decades; the life-or-death stakes take an extraordinary emotional toll; and successful outcomes are rare. The state made a desperate plea for volunteers. I agreed to take a case. People v. Marshall arrived in my office in cardboard boxes the following week.

A month later, a prison guard ushered me into a maximum security visitation room at San Quentin. The barred door on the other side of a glass divider rolled open, and Marshall, in his forties, average height with a muscular build, stepped into the room. He looked apprehensive as he sat down and grabbed the telephone receiver.

“Who are you?” he said. I’d sent him a letter of introduction, but the guards withheld his mail because he wouldn’t sign for it. I showed him the Court pleading appointing me as his appellate attorney. This didn’t seem to ease his mind. In the court below, he told the judge he believed his defense counsel was part of a conspiracy to rig his trial. He accepted my appointment that day, but I don’t believe he ever really trusted me.

I met with his trial attorney, Ron Slick. He was cooperative, but he remembered virtually nothing about the case and couldn’t answer any of my questions. I was surprised to learn later that he’d been appointed during the 80’s as trial counsel for a string of death penalty defendants. By the mid-90’s, eight of his former clients sat on death row, a California record at that time.

Giving up on finding any new evidence, we culled through the legal proceedings in search of reversible error. The effort dragged on for years. I left my law firm to become an executive, and one of my partners took the lead and filed the appellate brief.

From 1992 to 1997, the Court affirmed 84 death sentences and reversed only one. In 1997, People v. Marshall became number two. The Court held that the trial judge failed to give the jury a proper instruction on intent, reversed Marshall’s death sentence, and remanded the case to LA for a new trial.

We don’t know if Marshall ever learned that his death sentence had been overturned. My partner’s letters didn’t reach him because he continued to refuse to sign for his mail. When the guards came to remove him from his cell for transport to LA for the trial, he may have thought they planned to execute him. Whatever his reason, he resisted.

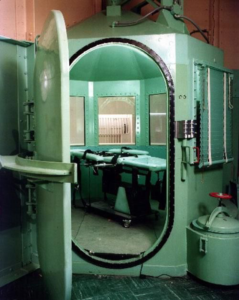

The cells on death row are windowless concrete boxes, about five by nine feet with very little head clearance. A strong man can mount a formidable defense from a rear corner. The guards couldn’t get Marshall out of his cell with normal force.

The cells on death row are windowless concrete boxes, about five by nine feet with very little head clearance. A strong man can mount a formidable defense from a rear corner. The guards couldn’t get Marshall out of his cell with normal force.

Inmates said the guards donned riot gear, shoved him against a wall with shields, and pepper-sprayed him while he screamed, “Please don’t kill me!”

Marshall died during the struggle.

My firm contacted a prisoner’s rights lawyer, but nothing came of it. San Quentin found no wrongdoing, listing Marshall’s cause of death as a “heart attack while being pepper-sprayed.” He was 51 when he died.

Marshall was from rural Louisiana. His father was a country preacher. He grew up working on farms. He moved to LA in his twenties. Starting in his late twenties, he was convicted of a series of crimes, most of them involving violence against women. With each offense, he would plead out, go to jail, be released, and start in again. I found no hint in the file about what, if anything, triggered the violence.

In a crowded field of vexing problems posed by the Marshall case, California’s administration of the death penalty troubled me the most. The overburdened lower courts seemed unable to do more than move Marshall along a conveyor belt of convictions, but once he was sentenced to death, the state poured more resources into his appeal than it spent on all the previous proceedings combined.

This approach has not worked for California. It leads all states with 750 people sitting on death row. The average direct appeal now takes 22 years to move from sentencing to a decision. Tacking on lengthy federal appeals, a California death sentence is tantamount to life without parole. The state hasn’t executed anyone since 2006 and 90 inmates are over 65 years old, some of their crimes dating back 40 years.

This approach has not worked for California. It leads all states with 750 people sitting on death row. The average direct appeal now takes 22 years to move from sentencing to a decision. Tacking on lengthy federal appeals, a California death sentence is tantamount to life without parole. The state hasn’t executed anyone since 2006 and 90 inmates are over 65 years old, some of their crimes dating back 40 years.

Meanwhile, California spends a fortune defending death sentences it will never carry out. The cost averages 140 million dollars per year, well over four billion since 1977, money the state could better spend on stemming the tide of violent crime. No matter what your opinion of capital punishment, the death penalty in California satisfies no one’s goals and should be abolished.

Post Script: I used a few of the basic facts of the Marshall case to spin a very different story in The Closing. In the novel, Kenneth Deatherage sits on death row in Virginia in the 60’s, a time and place when executions actually went forward and death row inmates were afraid for their lives. Deatherage claims local officials conspired to frame him. When Nate Abbitt, Deatherage’s lawyer on appeal, uncovers hints of corruption in the county justice system, the powers that be come after him and he finds himself fighting for his own life, as well as his client’s.

July 28, 2017 @ 2:19 pm

Ken,

Thank you for Whippoorwill Hollow. You brought back people I knew as a child. I miss them. I admit to shedding a few tears. Your writings are in the category of John O’Hara and Taylor Caldwell. Thank you again.

July 28, 2017 @ 3:34 pm

Thank you so much, Vera. I’m humbled by the high praise and grateful to you for reading my books.

June 26, 2017 @ 8:33 am

Chilling. Excellent blog.

June 27, 2017 @ 9:39 am

Thanks, Gay!

June 24, 2017 @ 3:05 pm

I still remember riding in the car with Pamela reading The Closing and just absolutely being blown away by the opening scene (and continuing on from there. Great story, great writing. Powerful stuff. Excellent bog here as well.

June 24, 2017 @ 3:25 pm

Thank you, Eric!