The Night Stalker

If you lived east of Los Angeles in 1985, as I did, you feared for the safety of your family. From March 17 to August 30, a Satan worshipper broke into homes and raped, tortured, and murdered those he found inside. He struck first in Rosemead, killing a woman and maiming her roommate. That same night he raped and killed another woman. Three nights later he raped an eight year old girl. The following week, he murdered a husband and wife.

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

The police seemed helpless to stop him. Sales of alarms and guns hit an all-time high. I installed an alarm system, dusted off a shotgun left over from my hunting days in Virginia, and kept it in my bedroom closet.

The Night Stalker killed and maimed with impunity all summer long until August 24, when he finally made a mistake. A teenager saw him drive away from an aborted break-in and remembered part of the stolen car’s plate number. The police found the car and recovered a partial print that identified the Night Stalker as Richard Ramirez, a 25 year old, small-time thief from El Paso, Texas.

The morning of August 30, Ramirez stepped off a bus on Euclid Street in East LA, walked into a liquor store, and blanched when he saw his mug shot plastered all over the newspapers. The store’s clerk cried out, “It’s him. The Night Stalker!”

Ramirez ran, and store customers gave chase, yelling, “El matador. The killer. Stop him.” Bystanders joined the hot pursuit as Ramirez weaved through streets, alleys, and backyards for almost two miles. Exhausted and desperate, he tried to hijack a woman’s car on Hobart Street. Her husband hit him with a metal pipe; he staggered up the block; and the crowd caught up to him. When the police arrived and pulled him free from the angry mob, he was bloodied, beaten, and begging for mercy.

With his arrest, the city’s long nightmare of murder and mayhem came to an end, only to be followed by a different kind of nightmare, a marathon of legal proceedings.

Pre-trial motions and hearings lasted for three years. His trial took another year.

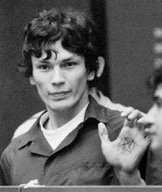

Hundreds of Satan worshippers marched outside the courthouse daily, carrying placards anointing him as their hero. Inside the courtroom Ramirez joked with his attorneys, flashed Satanic symbols at cameras, and laughed at witnesses who testified about horrific suffering at his hands. He told a deputy sheriff, “I love to kill people. I love watching them die … I told one lady to give me all her money. She said no. So I cut her and pulled her eyes out.”

On September 20, 1989, he was finally convicted of 13 counts of murder and 30 related felonies and was sentenced to death.

Never in fear of execution because of California’s lengthy appellate process, Ramirez reveled in his notoriety while living out his life on San Quentin’s death row. He granted televised interviews to Inside Edition, Mike Mattis, and other press outlets, fashioning himself as a philosopher-king among the Devil’s acolytes.

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.

One of his idolizers, Doreen Lioy, didn’t expect to fall in love with someone like Richard. Her friends from Burbank where she grew up described her as brainy and shy. She graduated from college with a B.A. in English Literature, became a free-lance magazine editor, and led a normal life until she saw Richard’s mug shot on television the night before his arrest. “I saw something in his eyes that captivated me, maybe the vulnerability.”

She sent him a birthday card after his arrest and visited him in jail during the pre-trial proceedings. She bought him clothes to wear in the courtroom and attended the trial every day.

After his conviction, she visited him on death row four days a week and sent him 75 letters. Her relentless campaign finally paid off in 1996 when Richard proposed marriage to her. He said he chose her over his other paramours because he trusted her. He was impressed that she was a virgin and a devout Catholic, who had come to accept his Satanic faith.

Doreen was overjoyed. “He’s kind. He’s funny. He’s charming … He’s my best friend. He’s my buddy.”

Always separated by a plexiglass divider, they had never touched. After Richard’s proposal, the warden approved their first contact visit. Doreen said it was “one of those defining moments.” She fell into his arms and he pulled her to him “softly and gently.”

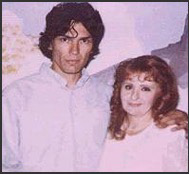

The wedding ceremony took place at 11:20 a.m. on October 3 in San Quentin’s general visiting area near the drink machine with a few friends looking on, mostly lawyers. A state employee officiated. Richard’s brother served as best man; his sister as matron of honor. Doreen’s family, having disowned her, didn’t attend.

The auburn-haired bride, 41, wore a knee-length white ruffled dress with iridescent pearls, white hosiery, and white pumps. No veil. The groom, 36, wore a freshly ironed prison-issue blue shirt, tail out, and denim slacks.

They exchanged gold wedding bands, one engraved with “I love you forever, Richard,” the other, “To my one and only love, Doreen.”

An observer said Doreen was nervous during the six-minute ceremony, but “Richard was very calm and loving, very tender … Doreen brings out the best in him; they complement each other.”

“I’m ecstatically happy today,” Doreen said, “and very, very proud to have married Richard and to be his wife.”

San Quentin doesn’t allow conjugal visits for death row inmates, so the marriage was never consummated, and as far as we know, Doreen remained a faithful virgin into middle age.

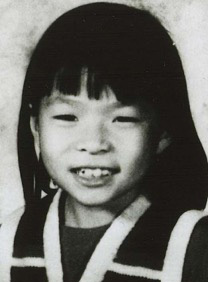

In 2009, DNA samples gathered in a 1984 cold case proved conclusively that Ramirez raped and brutally butchered a nine year old girl, Mei Leung, in a Satanic ritual human sacrifice so graphic even Doreen apparently couldn’t excuse it. Rumor has it she divorced him, but I could find no record confirming that.

A long string of state and federal appeals still lay ahead of Richard when disaster struck. He was diagnosed with incurable blood cancer, B‑cell lymphoma. He rotted away from the inside, his flesh turning a hideous shade of green in his final days, and he died on June 7, 2013, at the age of 53, in Marin General Hospital. The rumors about Doreen’s estrangement appeared to be true, since no one claimed Richard’s corpse.

So ends the story of the Night Stalker, but I wish his story had ended very differently.

In the final days of President Obama’s administration, anti-death penalty advocates worked hard to convince him to denounce capital punishment. He expressed grave reservations, but maintained that some crimes are so heinous “the community is justified in expressing the full measure of its outrage.”

The Night Stalker’s crimes were heinous to a degree beyond words. A lifetime of confinement was a grossly inadequate punishment for his defiant, unrepentant savagery, especially considering that he spent his time on death row enjoying his celebrity, laughing at his victims, courting his many female admirers, and even marrying one of them. Thinking about the final moments of Mei Leung’s life and those of his other victims, I wish the state had executed him swiftly and decisively. The truth is he deserved far worse.

March 1, 2018 @ 7:59 pm

Wow Ken, growing up in the islands and spending most of my life there insulated me a bit from things like you describe here. While I was aware of it, it seemed another world away and possibly not real. I agree with the sentiment that for some crimes, capital punishment is not enough .

March 2, 2018 @ 3:31 pm

This was a scary time. There aren’t too many people as bad as this guy anywhere. Thanks for following my blog. Your encouragement means so much to me.

February 26, 2018 @ 1:22 pm

Chilling article, Ken.

February 26, 2018 @ 5:56 pm

Thanks, Bobbye! You are a genius.

February 25, 2018 @ 7:40 pm

Ken,

This evil man’s life calls for an end to the death penalty. It would save society a great deal to take it off the table so that prosecutions can proceed swiftly and appeals be based on the merits of the case, not the morality of the punishment we impose. As noted by his vile life, in the end all of are going to die and we should leave the method up our Maker.

Matt Murray AHS ’65.

February 26, 2018 @ 10:15 am

Great to hear from you, Matt! My feelings about the death penalty are conflicted. I generally oppose it, but in extreme cases, like the Night Stalker, retribution for the victims moves me to support it. I agree with you, though, that capital punishment distorts the criminal justice system. In California, where more than 750 people sit on death row, the lengthy appellate process assures that no inmate will be executed while the state spends $140 million per year (over 4 billion since 1977) to administer it. California’s death penalty laws drain the system of resources, clog the courts, and thwart the goals of those on both sides of the issue.

As a counterbalance to the Night Stalker, I’m working on a post for next month about Earl Williams. Virginia came within a few days of executing him for a crime he didn’t commit. For me, his story presents one of the most compelling arguments against capital punishment. Thanks for reading my post and for your feedback!

February 24, 2018 @ 11:50 am

I wish the UK would implement the death penalty and when someone gets “life” it should be the rest of their natural lives „, not walk out of prison after 7 or so years. Legal system here is pathetic. I’m a strong believer in an eye for an eye.

February 25, 2018 @ 9:49 am

I agree with you, Ellen, that leniency to the extreme makes no sense. I’m not a big fan of the death penalty, but some crimes are so heinous and evil no other punishment seems to fit the crime. In my view, our criminal justice systems fail the citizenry when they pay more attention to the perceived rights of criminals than to the suffering of their victims.

February 23, 2018 @ 8:51 pm

Reading this brings back all those horrid, worrisome nights with only our 2nd story windows open. It was the scariest time with our little girls, especially after his fingerprints were found ON the outer windows of a house on Vista, near Sheffield in North San Gabriel ~ not 1/2 mile from us. Thank you for reminding us of all the details.… and yes, he didn’t deserve to live one more day after those heroes found him and gave him a piece of their hometown justice.

February 24, 2018 @ 9:47 am

I had forgotten those prints off Sheffield. We had moved to Bedford from Sheffield before he started his rampage, but it was still too close. Also, the first one in Rosemeade was near the AYSO fields where the kids played soccer. And Sierra Madre, three in Arcadia, two in Monterey Park, Pasadena — seemed like he was hitting all around us that summer. A scary time.

February 23, 2018 @ 7:20 pm

Ken,Those of us living the Pasadena area were not immune from the concerns of those other folks in the San Gabriel Valley. We all rejoiced when he was nabbed.

How about some info on another notorious killer—The Hillside Strangler.

February 24, 2018 @ 9:53 am

Researching this, I found that he struck once in Pasadena and once next door in Sierra Madre. It was a scary time. I’m not sure what happened to the Strangler, another child of Satan. I’ll take a look.

February 23, 2018 @ 7:16 pm

I remember the publicity around the case, both before and after his arrest. I agree with President Obama’s reasoning. Some criminals should never regain their freedom. Ramirez and Charles Manson both died in prison as they should.

February 24, 2018 @ 10:13 am

Strange system we have in California. The death penalty here is tantamount to life without parole. California has over 750 inmates sitting on death row, the most of any state, with more than a hundred over age 65, some of their crimes dating back 40 years. They die of natural causes, like Manson and the Stalker, or by suicide, but never by execution. (The state’s last execution was in 2006.) Pro and anti death penalty advocates both criticize California’s death penalty laws. My personal view is California imposes the death penalty too easily. It should reserve that sentence for the worst of the worst, like the Stalker, where there is no doubt of guilt, streamline the appellate process, and execute; or it should repeal the death penalty altogether and replace it with life without the possibility of parole. Either would be preferable to the current pretense of a death penalty.

February 23, 2018 @ 3:40 pm

Chilling, Ken. Makes one wonder if he was born that way, or was a victim of a horrible childhood. Either way, an example of pure human evil.

February 23, 2018 @ 4:58 pm

He had a horrible childhood, Gay, but nothing excuses the crimes he committed, in my view. Truly an example of pure evil.

February 23, 2018 @ 3:15 pm

He stalked my neighborhood as well as that where I worked. My kids were terrified.

Later, I was at the county courthouse for jury duty, and he exited an elevator, cuffed and ankle shackles in place. I can never forget his face.

February 23, 2018 @ 5:01 pm

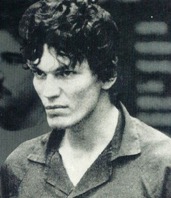

That first photo in this article was the closest I could find to the evil he projected, Lorrie, but even that falls short. It was a scary time.