The Lawyer

My wife was the driving force behind my decision to become a lawyer, but Johnny Carson actually clinched the deal. My wife and I were school teachers at the time. We thought we couldn’t support a family on our salaries, so we looked around for alternatives.

“Why don’t you go to law school?” she said.

“Too much tedious detail, poring over complicated documents, wrestling with boring rules and regulations.”

“I bet you’d like it.”

“I don’t think so.”

Over the next few months, she suggested law school again and again. I brushed her off each time without telling her the real reason. I thought I wasn’t smart enough. My G.P.A in college was a lackluster B-/C+. I didn’t think I could survive a law school curriculum, but my wife believed I could do it and I’d learned to trust her judgment.

Her gentle prodding had almost overcome my lack of confidence by the time Johnny Carson got into the act. I was watching The Tonight Show when he introduced F. Lee Bailey, Richard “Racehorse” Haynes, and Melvin Belli as the best lawyers in the country. They sparred with one another. Bailey was impressive, but the other two came across as complete duds. Years later I learned they were both great lawyers, but that night Racehorse was slower than a crippled mule and old Mel was almost comatose. If those two guys could rise to the top of the legal profession, I thought I’d be able to scratch out a modest living at it.

UVA’s law school, one of the best in the nation, was right down the road, but I figured my G.P.A. would disqualify me. My wife’s friend worked for the Dean of Admissions. She said the law school was required to take half its students from Virginia residents and the applicant pool for that group was thin. She thought I would make the cut.

I applied. UVA turned me down. They put me on a waiting list, but the call never came. Our friend thought I should try again. “Coming off this year’s waiting list,” she said, “they’ll give you priority.” I took her advice, taught for another year, and reapplied. As she predicted, UVA accepted me.

We penciled out a budget. My wife’s salary and the small amount we had saved up would cover tuition and living expenses if we pinched pennies. That summer, to cut costs, we moved from our house in Crozet to an efficiency apartment in Charlottesville.

At law school orientation in the fall, everyone I met was an Ivy League School Phi Beta Kappa, a veteran who had served as an officer in Vietnam, or an M.B.A. graduate. I had been rejected on my first try for admission, and I seemed to be the least qualified student in the incoming class. I figured I stood a good chance of flunking out even if I gave it everything I had.

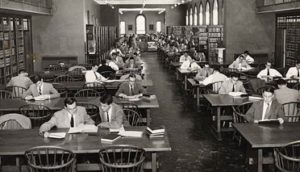

Abject fear proved to be a great motivator. My wife dropped me off at the law school every morning at eight and picked me up at five. I sat in the back of my classes, kept my mouth shut, and took copious notes. The rest of the day, I studied in the library. At night, I manned the desk in our bedroom until eleven.

One three-hour exam at the end of the semester determined the entire grade for each course. Five exams would decide whether I would sink or swim.

In January, the results of the exams were posted on bulletin boards, social security numbers on the left of the page, grades on the right. I was a dead man walking when I approached the first board. My eyes ran across the page from my number to the grade. I froze. It had to be a mistake. The grades posted on each successive board provoked the same reaction: This could not be happening.

I sat my wife down and broke the news to her. “We’re going to be okay,” I said. When I told her my grades, she jumped up and down and cheered.

The following semesters went just as well. Doors opened that we never dreamed we could walk through. Law firms recruited us lavishly. On our first interviewing trip, a firm put us up in a fancy hotel in Atlanta. Glass elevators zipped up and down a column inside the skyscraper. We rode to the top, stared wide-eyed at the lobby way below us, then rode down, and up and down again, like kids in a roller coaster park.

Those heady days passed quickly; graduation approached; and we had to decide what to do with our lives. In almost every firm I’d interviewed I’d met a weak link, and I used the Racehorse/old Mel rationale to reassure myself: “If that lawyer can succeed here, I can too.”

Latham & Watkins in Los Angeles was the sole exception. I’d met thirty attorneys. They were all great lawyers. No weak links.

I leveled with my wife. “I don’t know if I’m good enough to make it there.” The reasons not to accept Latham’s offer were daunting: Neither of us had been west of the Rockies until we interviewed Latham. Los Angeles was 3000 miles away from our families and everyone and everything we knew. We’d spent only six days in the city, not enough time to know if we’d like living there. And I might fail.

On the other side of the ledger stood a single, stark fact: I was convinced Latham was the best law firm in the country.

I was fifty-fifty on the decision. My wife tipped the balance.

After graduation, we wrestled our five cats into a cage, loaded it into our Pinto station wagon, and set out for Los Angeles. At the top of Afton Mountain, we stopped and looked back at the valley, not knowing if we’d ever return to this place we had loved so much. And we cried.

Six days later, we arrived in Los Angeles. After a week of arguing with landlords about our cats, I did what I had to do. I committed fraud. I signed a No-Pets lease and we smuggled the cats into an apartment on Gretna Green Way in Santa Monica, three doors down from the courtyard where O. J. Simpson would slash Nicole’s throat and stab Ron Goldman to death nineteen years later.

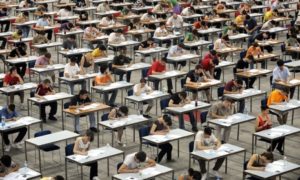

I went to work at Latham in June. In July, I took the California Bar Exam, the most difficult bar in the country with a failure rate of fifty percent. At that time, no attorney at Latham had ever failed it, and I assumed they would fire me if I washed out.

I entered an auditorium the morning of the exam nervous and overwrought and left three days later, feeling no better.

While we waited anxiously for the results, a paralegal who worked at Latham told me he’d failed the bar exam eight times. At a coffee shop, I met a Harvard Law School graduate who’d failed it twice. As the months dragged on, I met a small army of impressive graduates from good law schools who had failed the exam once or more.

I was on the verge of a nervous breakdown when the bar finally released the results to the press in December. My hands shook when I paid the old guy at the newsstand. I swallowed hard and found the page with the O’s on it.

Back at the apartment, I showed my wife the newspaper. She cheered again, but being eight months’ pregnant, she had the good sense not to jump up and down this time.

I practiced law at Latham for eighteen years. I did okay, and I liked it a lot.

Johnny and The Tonight Show gave me the last shove across the line, but my auburn-haired blind date is the one who called the shot and got it right. She knows me better than I know myself.

May 6, 2021 @ 11:09 am

Hello Ken,

Turns out we share a last name but I don’t know if we are related. Many times, I have received your mail but with my address, but just MCLE or law book notices, so not to worry. I loved reading your story — yes, people often can’t believe that we had to spend 3 days straight just to take the bar exam! And yet, time has flown by, and I’m about to retire from the practice of law. It has been quite a run. All the best to you.

May 8, 2021 @ 7:30 am

Great to hear from you, Susan. I have run across your name a few times, too, in connection with bar activities. Sounds like your time as a lawyer was as enjoyable as mine. Good luck in retirement.

April 14, 2019 @ 6:30 pm

Ken,

My daughter, who went to Univ. of San Diego law school, also passed the CA bar on her first attempt in 2003. Boy, I know the tension of that process, as she lived with us at the time — studied most of day/night for months!

April 14, 2019 @ 3:53 pm

Ken,

My daughter also passed the CA bar on her first try in 2003. She went to Univ. of San Diego law school. I know the tension she was under as she lived at home during that time; the whole family was tense!!

April 15, 2019 @ 8:24 am

Congratulations to your daughter and her proud dad. It’s a tough exam. They can question you on any area of the law and you feel like, somewhat justifiably, your entire future is on the line. I hope your daughter is enjoying the practice of law. It’s a challenging, interesting profession!

March 3, 2019 @ 8:33 pm

Ken — What a wonderfully written piece! Thank you for sharing your story. Trust and courage are among the most important qualities, along with persistence. Clearly you’ve always had that, and so much more. So, hats off to Cindy! Very best wishes, Belinda

March 4, 2019 @ 8:44 am

Thanks so much, Belinda! You guys were a big factor in our decision to come to LA, so it’s gratifying to know you think it was a good move. It’s fun to write these vignettes about the old days. Brings back such great memories.

March 2, 2019 @ 2:44 pm

An inspiring history, as they always are from you, Ken. This one’s all the more special because it’s yours. Thanks for sharing it.

March 2, 2019 @ 4:21 pm

Thanks, Gay! The personal stories are fun to write, although remembering the bar exam was not a pleasant experience. 🙂

March 2, 2019 @ 10:06 am

Dear Ken,

I loved reading this story and learning that Cindy gets all the credit!

I remember her telling me about your early days in Virginia and that you were writing a book. I had just began taking creative writing classes at the University of Iowa and wanted to read your work.

I’m so happy for you, your lovely family and for your newest grandson!

March 2, 2019 @ 4:19 pm

Thanks, Eva! Cindy runs the show around here. I come in fourth, behind the two dogs. Thanks for following my blog.

March 1, 2019 @ 6:39 pm

As usual, a very interesting story about a life changing event, the risk taking in making a significant career change and the dealing with the challenges of moving to a completely different culture. Thanks for sharing your life stories. I am really glad that the decisions you and your family made turned out well. Keep the stories coming! They are very good reads!

March 1, 2019 @ 9:02 pm

Thanks, Randy! I’m glad you like the life stories. They’re fun to write. I appreciate you following my blog and your comments and insights.

March 1, 2019 @ 5:00 pm

Yeah, you did okay. You did okay at Safeway too. And you are an okay writer.

March 1, 2019 @ 5:24 pm

I’m okay, striving for pretty good. 🙂

March 1, 2019 @ 3:25 pm

Great story. Great career. All of us were lucky to know you.

March 1, 2019 @ 3:53 pm

It’s great to hear from you, Mike! Thanks for reading my blog and for your very nice comment. I consider myself lucky to know you, too.

March 1, 2019 @ 2:26 pm

Kenny, this was a really enjoyable read! It was exciting to hear the backstory about your entrance into the law as a profession. It sounded like the California bar exam took 3 days to take.…. is that how long it actually took to complete it?

I had to go back and read a couple of other blog entries that I had not yet read just for fun. I absolutely love to read nonfiction stories about truly interesting people.

March 1, 2019 @ 3:51 pm

Thanks, Betty! The California bar exam took three days. First day — eight one hour essays. Second day — hundreds of multiple choice and true-false questions. Third day — four one hour essays in the morning, then forty multiple choice and true-false questions about ethics in the afternoon. It was pass-fail, and if you passed, they didn’t tell you anything about how you did. I don’t know whether I passed by one tenth of one percent or by a wide margin (not likely), but when I saw my name on the pass list, I didn’t ask any questions for fear they’d discover they’d made a mistake! Thanks for following my blog!

March 1, 2019 @ 1:59 pm

Loved this peek into your past and most of all the vision of you, your wife, and 5 cats in a Pinto taking off for your cross-country adventure. Brave indeed. You’ve come a long way, “Kenny!”

March 1, 2019 @ 3:42 pm

Thanks, Susan! I could write an entire blog about cat-travel-hysteria, non-stop cat shrieks for the seven days and nights of that trip. By the time we reached LA it did indeed seem like we had come a loooong way!

March 1, 2019 @ 1:49 pm

Great story again Ken only I guess this time it’s fiction at its best! You and your wife’s persistence paid off! You have much to be proud of! I miss those Afton mountains, too flat here.

Hard to believe you were only 3 doors down from all the action. Guess you saw a lot! Another book???

March 1, 2019 @ 3:39 pm

Thanks, Polly! I was so lucky to find that photo of the view from Afton Mountain, but the truth is the camera doesn’t do it justice. No book coming from me about OJ. Too many already address that topic. I’m working on another mystery, though.

March 1, 2019 @ 12:12 pm

I love your blogs, and I love Cindy. Great one, and, as usual, I see the modesty of your upbringing here. You were a legal rock star. 🙂

March 1, 2019 @ 3:35 pm

Thanks, Pamela, as always for your encouragement. Coming from a great writer and a great lawyer, it means a lot to me. Still get a smile on my face when I think about how much fun I had talking with you the other day, as much when the tape was off as when it was on. Hoping I can move some things around and make it to your October conference.