Irv the Liquidator

On the morning of April 10, a visitor to the home of Irwin and Alexandra Jacobs found them lying in bed, both dead from gunshot wounds. They had lived for 40 years in their home on Lake Minnetonka in Minnesota. High school sweethearts, they had been married for 57 years. They had five children and eight grandchildren

The medical examiner determined that Irwin shot Alexandra and then turned the gun on himself. One of Irwin’s friends said Alexandra “had been in a wheelchair for the last year or so and had signs of dementia. Irwin was … distraught over her condition.”

I’m still reeling from the news. I’d known Irwin Jacobs since 1983, when he made a bid for Kaiser Steel and hired me to evaluate the company’s labor problems.

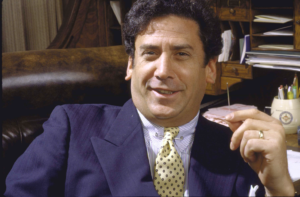

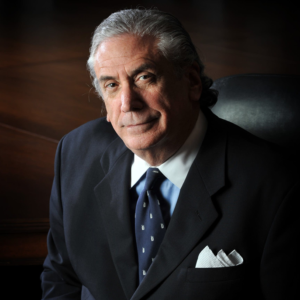

When he called me, I wasn’t sure I wanted to represent him. He was a high-profile “corporate raider” with a mixed reputation. The business press dubbed him “Irv the Liquidator” for breaking companies apart and selling off the pieces. Executives, who feared he’d fire them if he gained control, fought his takeover bids hammer and tong. In those battles, he gave them no quarter. His enemies considered him a no-holds-barred street fighter, unethical and at times lawless.

Irwin’s hardscrabble background gave credibility to the street fighter image. When he was in grade school he worked for his father, a Russian immigrant who collected old burlap bags from Minneapolis’s grain elevators, repaired them, and resold them. When Irwin was 18, he drove a truckload of reclaimed bags past a burned-down warehouse and wondered what had been done with the items stored inside. That inspired him to launch a business with his father’s help salvaging fire and flood-damaged goods. Those early experiences taught Irwin “to throw nothing away” and “to look for value where other people didn’t see it,” lessons that later served him well in the dog-eat-dog corporate takeover arena.

In the 70’s, he purchased small undervalued companies, often out of bankruptcy, reorganized them, and sold them for big gains. Those deals fueled investments in even larger companies. He made runs at Pabst Brewing, Disney Productions, and Avco, selling out to higher bidders in each case. By 1983, this recycler of burlap bags with no formal education beyond high school had accumulated a net worth of $200,000,000.

When I met him, I saw no hint of the press’s shady character. Granted, he was a little rough around the edges. His grammar wasn’t perfect; he loosened the knot in his tie when he got excited; and his shirttail wouldn’t stay tucked in. But I liked him from the outset. A big man with a booming voice, a winning smile, and a great sense of humor, his boundless optimism was infectious. He wanted an honest assessment of Kaiser Steel’s disputes with the United Steelworkers. I spent two months evaluating those issues and gave him my conclusions. Someone came along and outbid him, and he sold out.

I thought I’d seen the last of him, but the following year he hired me again, this time to conduct an internal investigation of an LA based company he owned. A Texas lawyer alleged that the company’s in-house attorneys made him pay them bribes for assigning him legal work. Through a convoluted scheme set up by the in-house lawyers, they paid the Texas lawyer back for the bribes with company funds so he didn’t lose out. The Texas attorney thought the company’s General Counsel (GC) was the mastermind behind the embezzlement scheme, but he had dealt exclusively with a junior in-house lawyer and had no proof of that.

The fifty-year-old GC was a former president of the bar association and a pillar of integrity in the legal community. Irwin’s company paid him a half-million dollar annual salary and he sat on its Board of Directors. It seemed unlikely he would risk his career on a bribery scam, and there was no documentation implicating him.

When I questioned him, he put up a good front and denied everything, but I thought he was lying. Subsequent events confirmed my suspicions and triggered an undercover investigation run by the U.S. Attorney.

At the FBI’s direction, I spent a week talking with most of the company’s outside attorneys, asking them if they’d paid kickbacks to get legal assignments. They all denied paying bribes. Several of them then called the GC in a panic and made incriminating statements on phone lines the FBI had tapped.

Meanwhile, the junior in-house attorney, who had dealt with the Texas lawyer, agreed to cooperate with the investigation in exchange for immunity. In a taped meeting with the GC orchestrated by the U.S. Attorney, he offered to take the fall for the kickbacks and keep the GC out of it for a $100,000 bribe. In a second taped meeting in Encino’s Balboa Park late at night, the GC handed the junior attorney a paper bag full of cash. He sounded crazy on that tape, and he talked about doing harm to Irwin and me.

The next day, the GC snapped, bought a rifle at a Big 5, and holed up in his house. The FBI managed to take him alive, but the arresting agents said that the rifle misfired and that he begged them to turn him loose and let him run so they could shoot him in the back. A suicide note in his pocket blamed his troubles on “Irwin and his fleas.”

When the GC was released on bail, Irwin insisted on hiring round-the-clock bodyguards for me. In hindsight, I don’t think I was in any real danger, but at the time I wasn’t sure and Irwin refused to take a chance, so for a couple of weeks two big hulking guys with guns were my constant companions.

The GC eventually pled guilty. At his sentencing hearing, big name lawyers filed letters attesting to his good character, and his defense attorney argued he should be given probation and no jail time. When the judge sentenced him to five years in prison, he fainted.

I worked with Irwin off and on for the next decade. I felt as close a bond with him as with any client I ever represented, but when I left the practice of law in 1993, we lost contact. I was busy trying to help turn around a struggling company and I didn’t keep in touch. He bought an interest in the Minnesota Vikings, and I saw him on television in the owners’ box every so often. Each time, I thought about calling him, but I never did.

When the news of the murder-suicide broke on April 10, I hadn’t thought about him for a long while. Since then I haven’t been able to stop thinking about him.

He didn’t deserve to go out this way. He was gracious and genuine, a straight-up good guy, who was fun to be with, even in the most stressful times. His greatest joy was his family. He glowed when he talked about his kids, and he was particularly proud of a grown daughter who had cerebral palsy. He bragged to me about her independence and how she lived and worked on her own.

He met his wife, Alexandra, when they were seventeen, and he was crazy about her. An accomplished studio artist, she was his first and only love.

Irwin’s friend said he couldn’t stand to watch her go away. Dementia is a cruel descent into hell. I’ve lost three friends to it. I don’t know how their loved ones found the strength to confront the unfathomable heartbreak and loss, but in each case they persevered with heroic courage, stamina, and love. Irwin couldn’t do it. I won’t blame him or judge him for that. No one should.

I blame myself, though, for losing touch with someone who meant a lot to me.

September 21, 2023 @ 2:07 pm

For some reason, I was thinking about Erwin and Alex today and came across your article. I graduated high school with both of them, but knew them both from grade school.

They were real people.

September 22, 2023 @ 7:50 am

Thanks so much for your comment. I didn’t know Alex except through Irwin’s stories about her and his family. He loved her and his children with all his big heart. I cared a great deal for Irwin and was shocked and saddened beyond words by his passing. So sorry for your loss of your friends.

June 13, 2019 @ 2:13 pm

Nice article, and tragic story. I have many clients who became friends, and like you, I have lost touch with some of them. The article has resulted in my sending out a few emails. Thanks Ken.

June 15, 2019 @ 7:23 am

I’m glad the story inspired you to reach out to old friends. Wish I’d thought to do it long ago.

June 1, 2019 @ 5:53 am

As the junior associate on the bribery case you describe, I remember vividly every aspect of the case. I concur in your description of the events as well as your conclusion about Irwin. Imagine a client sending Christmas gifts to a junior associate whom he knew from a single case. And doing so every year for almost a decade, even though we had no continuing contract. That speaks volumes about Irwin as does your eloquent story. And thanks, Ken, for all the lessons you taught me on this and many other assignments.

June 1, 2019 @ 7:12 am

I learned a lot from you, too. Heady times we had together. Scary, too, at times. I remember our worrying during this thing whether we’d make it to our next birthdays. Irwin was a great guy. It was a sad shock to learn about his death. I wish things had turned out differently.

June 1, 2019 @ 4:22 am

Great story. Bet you have many more from your career.

June 1, 2019 @ 7:08 am

Thanks, Mike. I have a few more, but the GC part of this story was the most exciting. Too exciting at times.

May 31, 2019 @ 2:33 pm

Thank you for sharing this ?

May 31, 2019 @ 4:34 pm

Thanks, Janet.

May 31, 2019 @ 11:06 am

I am so sorry for your lose. What you wrote was very heartfelt.

My husband and I over the last four years have been caregivers for my aunt who has dementia. This past February it got to be too much for us so we had to put her in assisted living. Being a caregiver for a person with this disease is very difficult. It consumed and drained us. I can understand why your friend did what he did. It’s very hard to see a person you love disappear right before your eyes.

You sound like a very loving and caring person. Don’t beat yourself up. Sometimes life has a way of just taking you in a different direction. You care. That is what is important.

May 31, 2019 @ 4:33 pm

Thank you for your kind words and thoughts. I just wish this hadn’t happened, of course. He was such an optimistic energetic guy. This disease is so awful.

May 31, 2019 @ 11:04 am

I have known several people who have chosen to end their lives early. A few who also ended the life of a loved one who they couldn’t live without. My grandparents were married for 53 years when my grandmother died from cancer. They were each other’s best friend. Grampa stuck it out for 11 months until God blessed him with a fatal heart attack. He was in horrible misery that year. He visited friends and family, stayed as busy as he could and finally re-joined a card club that they had belonged to as a couple. I would not have wished his horrible year on anyone.

I understand the pain that your friend was in, I cannot judge him either. All we can do is appreciate the friends and family we have, make every day count and be thankful that we knew them.

May 31, 2019 @ 4:30 pm

Thanks for sharing your personal stories and for your last paragraph of advice. I agree with you. I just wish they’d find some cure or at least something that slows down the deterioration. My dad had dementia at the end. They couldn’t seem to get the drugs right. When he was on them, he was a vegetable. When he didn’t take them, he was physically strong, but he saw people and things that agitated and frightened him. He was ninety three, though. The most heartbreaking situations I’ve seen involve early-onset Alzheimers. It hits people in their late forties or early fifties and moves quickly. More research will lead to relief, I hope.

May 31, 2019 @ 10:52 am

Ken: interesting and sad story. I vaguely recall the bodyguard situation.

May 31, 2019 @ 4:23 pm

It is very sad. The only light moment for me when I wrote it was recalling running into Clint in the hallway with one of my bodyguards about nine one night. He thought I was joking at first. Then he became alarmed and asked if we should get security for the firm. We didn’t. The risk was overblown. A harrowing couple of weeks, though.

May 31, 2019 @ 10:46 am

Beautiful, Ken!

May 31, 2019 @ 4:13 pm

Thanks, Eva. It was hard to write.

May 31, 2019 @ 10:34 am

OK, I cried. <3

What a wonderful tribute, Ken.

May 31, 2019 @ 4:12 pm

Thanks, Pamela. This one was hard to write. I cried, too.

May 31, 2019 @ 10:13 am

Ken, a great story. I kind of forgot about him even though I remember when he was at his peak. Hope all is well. Jim

May 31, 2019 @ 4:12 pm

Thanks, Jim. Contrary to some of his press, he was a good guy.