My First Court Appearance

The client was a liquid bulk storage terminal in San Pedro, California. A faulty pipe coupling spilled twenty-two gallons of an acetate chemical compound at the foot of a huge tank. Technicians cleaned it up quickly but not before the wind blew noxious fumes into a nearby trailer park. The residents filed complaints with the county’s air pollution agency about the horrific stench, and the agency charged the terminal with a criminal misdemeanor for causing a public nuisance.

I was a freshly minted member of the bar when the case fell on my desk. My job was to appear at the arraignment and plead it out. “This’ll be an easy first court appearance for you,” my Latham supervising attorney said. “Meet with the prosecutor before the hearing. Tell him you’ll plead nolo contendere (no contest). Try to negotiate a fine under a thousand bucks, but anything up to two grand is okay. The judge will rubber stamp whatever the prosecutor agrees to.”

“What if the prosecutor won’t agree?”

“He’ll agree. Prosecutors hate these piss-ant cases. So do the judges.”

I arrived at San Pedro Municipal Court early and found the prosecutor in the hallway outside the courtroom. A short guy with black hair that fell to his shoulders,

he was as inexperienced as I was. He sneered when I offered to plead nolo and pay 500 dollars. Fashioning himself as a young Ralph Nader on a crusade to destroy corporate America, he refused to agree to anything.

I was in a state of semi-panic when the judge took the bench. In his sixties, portly with dark bags under his eyes and a receding hairline, he asked me to enter a plea.

“Nolo contendere, your honor,” I said, my stomach bathed in acid.

Young Ralph Nader objected, stating he wanted to try the case to a guilty verdict.

The judge looked at him like he was crazy. “I’ll accept the defendant’s plea. What fine have you agreed to?”

“We have no agreement,” Ralph snapped, obviously miffed that the judge wouldn’t go to trial. “The district demands a fine of twenty-two thousand dollars, a thousand dollars per gallon spilled.”

I almost fainted.

Twenty-two thousand smackers would constitute a world record fine for a public nuisance misdemeanor. I’d never live it down. “But this was an accident,” I said, my voice cracking. “The company cleaned up the spill immediately. Anything over five hundred dollars would be a travesty.”

The judge threw up his hands. “You’re miles apart. How am I supposed to decide this?” Frowning, he paged through the case file. “I have no idea what this chemical smells like. One of these citizen complaints says vomit. Another says rancid milk. Some creative soul describes it as burned ass.” He held up one of the forms to us. “This one says human feces, using the four-letter word.” He slapped it down on the bench and glared at Ralph and me. “I can’t rule until I’ve smelled this chemical for myself. Collect a sample from your client, Mr. Oder. We’ll reconvene tomorrow morning.”

Stunned, I limped back to my office. “I didn’t think it was possible to screw up a misdemeanor arraignment,” my Latham mentor said. “You’ve proved me wrong.”

The client’s in-house counsel was equally impressed. “When the judge gets a whiff of this stuff, he’ll give us the death penalty.”

He brought a four ounce vial of the chemical to my office. When I was a teenager, I went rabbit hunting with a friend. His beagles caught a skunk. The dogs retched. My friend and I did, too. The four ounce sample of the acetate compound smelled worse than skunk juice. I agreed with in-house counsel. Death by asphyxiation in California’s gas chamber seemed like a fitting penalty for spilling twenty-two gallons of this stuff.

I placed the vial inside a cardboard box and jammed packing material around it in a vain attempt to contain the fumes. The next morning, unsuspecting victims I passed as I walked down the hall to the courtroom made sour faces and stopped to look at the heels of their shoes.

The judge wanted to inspect the sample in chambers. Ralph and I sat down across the desk from him. I unpacked the vial, pulled the stopper, and held it out to the judge. “Be careful, your honor. It’s powerful.”

He stalled out two feet from the lip of the vial, clamped both hands over his nose and mouth, fell back in his chair, and frantically cranked open the window behind him.

“Twenty-two thousand dollars!” Ralph crowed triumphantly.

So this is what I gave up a rewarding career in teaching for, I thought, opposing this jerk in a futile effort to persuade a judge twenty-two gallons of human feces doesn’t stink to high heaven. Welcome to the practice of law.

I put the vial back inside the cardboard box and braced myself to face the judge’s wrath.

It didn’t come. Instead, he gazed out the window somberly. A full minute passed. He didn’t move. He didn’t say anything. His behavior seemed strange, but he was the judge so I kept quiet. Ralph did the same.

The judge finally turned to me. “I can’t believe your name is Oder,” he said.

That was close to the last thing I expected him to say, but with a name like mine you learn to roll with the punches. “Yes, well, it’s a safe bet I won’t name my first child Acetate,” I said.

The judge chuckled, then stared at me pensively. “How long have you been with Latham?” he asked.

“Since June.”

“Where are you from?”

“Virginia.”

He perked up. “Beautiful country. I was stationed at Quantico in the Marines.”

“I grew up south of there, near Charlottesville.”

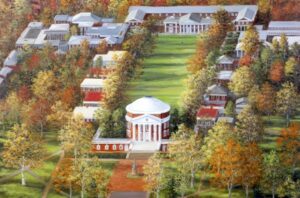

“I dated a girl at Mary Washington from Charlottesville. She showed me around Monticello, the University of Virginia.”

“I went to UVA. Undergraduate and law school.”

“Spectacular campus. The colonial architecture, the manicured grounds, the mountains in the background. You must have loved it there.”

“I did.”

“Why the hell did you move out here?”

“To join Latham.”

He nodded, a wistful look on his face. “I see.”

“Shouldn’t we be discussing the amount of the fine?” Ralph said.

The judge looked at Ralph like he was the one who smelled bad. “The fine,” he said. “Yes, of course.” He gave me a sad look and sighed. “I’ll rule from the bench,” he said.

We went into the courtroom. The judge took the bench and the clerk called our case. “The defendant will pay a fine of one hundred fifty dollars,” the judge said. He rapped the gavel, stepped down, and exited the courtroom through a back door.

Ralph looked like he’d been hit in the face with a baseball bat.

I was surprised, too, but on reflection, I understood. The judge presided over nothing but small claims. A thoughtful man, he was bored out of his mind. Our conversation took him back to his youth and Virginia, a time and place he much preferred over the present. I went there with him. Young Ralph resented the diversion and dragged us back to the courtroom, thereby deftly snatching defeat from the jaws of victory.

Back at Latham, the reaction was mixed. The fine was spectacularly low, especially considering the judge got a snoot full of skunk juice, but it took me two court appearances to get there so the legal fees were double. A mediocre result in a “piss-ant” case.

My first court appearance was nothing to brag about, but its lessons stayed with me for forty years: When the merits are completely against you, the best argument may be no argument; and in every case there’s more at play than the merits.

March 22, 2020 @ 1:48 pm

Ken

I am always looking forward to your tales of courtroom adventure and misadventures.

Thanks for keeping your fans entertained

March 22, 2020 @ 3:35 pm

Thanks, Terry!

March 3, 2020 @ 7:39 am

Very amusing story. The few times I have been in small claims or district courts it’s been interesting to see grass roots justice, as well as hear the number of lies a judge has to listen to and decipher on a daily basis.

March 6, 2020 @ 9:10 am

A lot of rough-and-tumble justice occurs in the muni courts. It can be interesting to watch, but maybe not so challenging to adjudicate. The judge in my case was bored out of his mind. He was nearing the end of his career and it seemed he wasn’t happy about how he was finishing up.

February 29, 2020 @ 11:07 am

Ken that was hilarious. I loved it. Pamela read it to me in the car and we both laughed out loud.

March 1, 2020 @ 7:31 am

Thanks, Eric!

February 29, 2020 @ 7:56 am

Thank you for sharing that story love the way you write it’s easy to visualize and feel like I’m there ?

February 29, 2020 @ 8:10 am

Thanks, Janet!

February 28, 2020 @ 7:43 pm

Oh, Ken, I laughed SO HARD ! ! !

February 28, 2020 @ 10:13 pm

Thanks, Pamela! It’s a lot funnier now than it was in forty-four years ago.

February 28, 2020 @ 6:56 pm

Ken,

Ben Turner would be proud. Great story!

Matt

February 28, 2020 @ 10:12 pm

Thanks, Matt! You could give me no greater compliment.

February 28, 2020 @ 3:43 pm

What a fun, stinky story and happy to see my alma mater, Mary Washington, played a role!!!

February 28, 2020 @ 5:18 pm

If I had a dollar for every former Marine who told me he dated a girl at Mary Washington, I could pay someone else to write these blog posts. I hope you stayed clear of those guys, at least the ones I knew!

February 28, 2020 @ 3:38 pm

A funny start given your surname.

But an enjoyable and humorous story with a slightly bit perhaps not I expected conclusion.

I had a few chuckles along the way so thank you for sharing your story and I’m sure a few more presented themselves over t he years.

February 28, 2020 @ 5:14 pm

Thanks, John. The luck of the draw was against my surname on my first case. Funnier to me today than it was back then, but I enjoyed that little case despite the setbacks.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:14 pm

Ken… I just now was able to stop howling with laughter after reading the judge’s thoughtful remark about your name. You may have another future in standup comedy! Great timing…

February 28, 2020 @ 2:35 pm

Thanks, Eric. Believe me, it wasn’t as funny then as it seems now.

February 28, 2020 @ 1:29 pm

I remember hearing about this legendary appearance during my first summer with the firm in 1976. Come to think of it, I heard about it from you. Reading about it now constitutes corroboration, so it must be true.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:35 pm

It’s true. I wasn’t happy about it at the time, but it made for a good story and I’ve been telling it for 44 years. You were one of the first to hear it, I guess.

February 28, 2020 @ 12:58 pm

What a great story, Ken! Irony, humor, puns… the whole package.

I’m still smiling.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:32 pm

Thanks for your kind words! I really appreciate you following my blog.

February 28, 2020 @ 12:23 pm

Your last line says it all. Whether it’s prosecution or defense, custody, adoption, abuse, or commitment, nobody in the courtroom ever knows the real story.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:31 pm

So true, Gay. In the courtroom, so much swims beneath the surface.

February 28, 2020 @ 11:46 am

Great story. I recall a few other- you “can’t lose”- stories from my days at LW. Some are classics.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:28 pm

Thanks, Ursula. There were a lot of great stories there. Someone should collect them and write a book. Don’t look at me. I’m two books behind schedule already.

February 28, 2020 @ 11:43 am

Ken — you probably (hopefully) don’t recall how you saved my ass when I screwed up a criminal OSHA case to the tune of a lot more than $150 or how I almost got fired after John WELCH dumped a loser arbitration on me for my first one of those. I seem to remember all the mistakes instead of all the successes.

February 28, 2020 @ 2:27 pm

I don’t remember those cases or you making mistakes, but I remember everyone of mine, in living color.

February 28, 2020 @ 11:16 am

Wonderful story, Ken. Everyone of us has a great or two story in our past. You have a lot more than that and have a wonderful way of sharing them through your written words.

Charlottesville, eh? I’ll have to visit there one day. ??

February 28, 2020 @ 2:25 pm

Thanks, Lucian!

February 28, 2020 @ 11:13 am

Another great one Kenny!

February 28, 2020 @ 2:25 pm

Thanks, G.A.!

February 28, 2020 @ 11:05 am

I love this story, don’t always believe what your mentor says, he’s not in the courtroom you are!

February 28, 2020 @ 2:24 pm

Thanks, Graham. So true about the mentor. You never know what will happen in the courtroom until you’re there.