Against All Odds

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles.

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles.

On my son’s fifth birthday, his stomach was distended and he complained of nausea. Our pediatrician misdiagnosed it as a digestive problem. When the swelling spread to his face, arms, and legs, a team of doctors identified his illness as a rare condition where the kidneys strip protein from the system. Without protein, water seeps from the bloodstream into tissue and organs, causing swelling, which can lead to infections, blood clots, and kidney failure.

By the time they diagnosed his disease correctly, his survival was in question. After two miscarriages, Cindy was four months pregnant. To control the strain on her as best we could, I took the lead with my son’s crisis.

I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps.

I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps.

When they’d purged all the stagnant water, the doctors built him up with injections of albumin. He would cry each time the doctor unveiled the needle. We tried to turn it into a game. “How long can you hold out before you cry? Bet you can’t make it all the way through the shot?” On day five, the doctor and I cheered when he took the injection without flinching.

His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not.

His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not.

On the sixteenth day, they cleared my son to go home. In the discharge conference, the doctor said we still had a long way to go. His condition was chronic. Relapses are virtually inevitable. The steroid, prednisone, would help his kidneys function properly, but because of its harsh side effects, he could only take it in six-week intervals. After each cycle, his kidneys would perform normally for an indefinite time, then break down again. I was to test his urine daily. When he relapsed, we would resume the prednisone.

“How long will this last?” I asked the doctor.

“Most children carry the disease into their late teens, some into young adulthood. You must be vigilant. An undetected relapse can be as serious as the first episode.”

Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

At the hospital, I’d learned a hard lesson. Time with my son was precious and irreplaceable. I vowed not to squander the second chance I’d been given. I volunteered to coach his soccer and T‑ball teams, signed up for Dodger season tickets, and planned weekend activities for us to share. On one of our outings that spring, we went to Santa Anita Park, a beautiful racecourse with manicured dirt and turf tracks and a grass infield. My son picked the horses; I placed our two-dollar bets; and we played catch on the grass between races.

In the eighth race, he picked number three. We went to the paddock where you can see the horses up close. Number three didn’t look like much. Sweating and foaming at the mouth, the undersized five-year-old bay gelding seemed nervous and unruly. We can kiss that two bucks goodbye, I thought.

From the bleachers, we watched three come from way back in the pack to pull ahead in the stretch and win by a half-length. We hugged and cheered, and for a short while, I forgot about the dark cloud hanging over us.

The following Monday, the stick turned gold; lime green the next day; then hunter green. We resumed the prednisone doses. The cabbage patch face, weight gain, and moodiness returned. Six weeks passed, and we stopped the drug again.

Cindy gave birth to our first daughter in June, and she became a second source of love and joy.

Another relapse came in July, followed by another round of prednisone.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.

He started the race badly, falling ten lengths behind and staying there all the way down the backstretch. Seven lengths off the lead going into the last turn without much track to go, he seemed sure to lose.

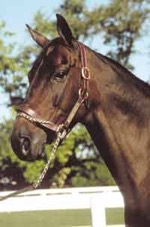

We stood on the rail about fifty feet from the finish line. I looked down the track and got a head-on view of him coming up the final stretch. I’ll never forget that snapshot image, forelegs pounding the turf like pistons, clods flying up behind him, wide glossy chest rippling with muscle, ears laid back, nostrils flared, head and neck pumping powerfully with each stride.

The track announcer’s bass voice boomed, “Here … Comes … John … Henry!” The crowd roared, and a chill went up my spine. He pulled ahead by a nose as he thundered by us and he buried the field by two lengths at the wire.

The gallery went wild. My son and I did, too. It was one of the most thrilling moments we’d ever shared.

Days passed into weeks, then months, and the sticks remained yellow. In August 1982, we reached the one-year mark without a failed test.

Complacency is your enemy, I told myself. Relapses are inevitable. You must be vigilant.

That fall we went to the track to watch John Henry run again. By that time, he was famous and even infrequent racetrack patrons like me knew his rags to riches story. With no pedigree, undersized, ill-tempered, and back at the knees, John Henry ran poorly as a young horse. A series of knowledgeable owners sold him for a song until Sam Rubin, a racing novice, bought him for $25000 sight unseen against a veterinarian’s negative recommendation. Frustrated with John Henry’s lackluster performances, Rubin fired his trainer, moved him to California, and placed him with Ron McAnally.

Known for his affection for his horses, McAnally and his staff bonded with the fractious bay gelding, training him with carrots, apples, and tender loving care. It worked.

In 1981, McAnally put John Henry up against the best horses in the world, and he won six major stakes races, including the two my son and I watched.

When my son and I returned to the track in the fall of 1982, he was seven years old, long in the tooth for a racehorse, but he hadn’t lost a step. He won that race with his patented, heart-pounding, come-from-behind charge, and my worries again fell away for at least a few moments as we joined the crowd’s frenzied cheering for The People’s Champion.

By the time the summer of 1983 rolled around, John Henry was still winning races, and my son kept testing yellow. In August, shortly after we passed the second anniversary of the last green stick, the doctor called me.

“No child has ever relapsed after two years of normal kidney function,” he said. “Very few children outgrow the disease before their teen years. Congratulations. Your son is now one of them.”

It took me a few moments to find my voice. “Thank you for everything.”

My son grew up to be strong and healthy. A successful businessman today, he’s married with two children and his kidney disease is a distant memory of a crisis that forged an iron bond between us.

After setting the lifetime purse-earnings record of $6,597,947 and winning every significant award in horse racing, John Henry retired at ten years old. A newspaper article celebrating his improbable success against all odds said he lifted the spirits and touched the lives of thousands of people. My son and I were two of them. He brought us thrills and joy when we needed them most, and his determined charges down the final stretch, running on pure heart and guts, refusing to give up, inspired me to persevere and gave me hope.

John Henry lived in the Hall of Champions at Lexington’s Kentucky Horse Park until his death in 2007 at age 32. It seems a touching twist of fate that the cause of death was kidney failure.

June 21, 2021 @ 10:51 am

Hello Ken

I just discovered you through reading Keeping the Promise on Kindle. You have a new, avid, fan and I’m off to find and read your novels too.

Some people say that blogs have had their day but I don’t agree. Most social media is fleeting, but blogs are like family letters. I have come to know and respect many exceptional people through the glimpses they offer in their posts.

I look forward to reading more from you!

June 23, 2021 @ 8:52 am

Thanks, Megan. I agree with you about the value of blogs. Thanks for reading Keeping The Promise and I hope you enjoy my novels.

June 5, 2021 @ 4:41 pm

Hi Kenny! It takes me a while to get around to my reading but when I get around to yours it’s always interesting and exciting reading! I love your writing and your modesty. You hold my attention and that is hard to do! Your beautiful example and your creativity helping your son through his very serious health years had to have had an effect on his many successes. What a beautiful family you have. I wish I had known what a treasure you were in our composition class at Albemarle High School. I knew you were a very nice guy but I had no idea of your hidden talent! Thanks so much for sharing your treasured stories. Your friend, Linda Beasley Graham

June 7, 2021 @ 9:21 am

Thanks, Linda. I always appreciate your comments. Wish we could go back to those high school days, knowing what we know now. There are so many friends like you that I would like to have known better. As Billy Kirby said in Old Wounds to the Heart, “When you’re young you’re too stupid to make good decisions. By the time you learn enough to make the right choices, it’s too late …” He had a much worse case of this kind of thing than I do, but I sometimes wish I had a chance to live through some experiences a second time and do it differently. High school is one of them. Anyway, thanks for your kind words and encouragement. They mean the world to me.

June 1, 2021 @ 10:28 am

Ken, you are so modest, you did not mention his athletic accomplishments. I coached in San Marino for many years and missed coaching him by just one year. When coaching freshman baseball I again missed him by a year. I wrote the high school sports column for our local paper and he was all League in both baseball and as a wide receiver in football. Later a college baseball player at Pepperdine. Not a bad comeback for a really nice kid.

June 2, 2021 @ 7:20 am

Thanks, Terry! I didn’t want to brag on him too much, but I’m very proud of his athletic achievements and his many other successes. After this close brush with losing him, though, I would have been thankful for every day we had with him no matter what he did. Thanks for reminding me of all those good times on the field of play.

May 29, 2021 @ 7:20 pm

Thank you Ken for once again reminding us that you cannot give up hope in any circumstance.

May 30, 2021 @ 7:27 am

Thanks, Ursula. So true.

June 1, 2021 @ 9:48 pm

Inspiration in our lives comes from the most unexpected places. Yours came from a race horse, and what you said here inspired us all. Thank you.

June 2, 2021 @ 7:22 am

Thanks, Dan! Telling this story was a labor of love and your kind comments mean the world to me.

May 29, 2021 @ 4:50 pm

Beautiful and thanks for making me cry <3 deeply touching

May 30, 2021 @ 7:26 am

Thanks, Janet. This one almost wrote itself.

May 29, 2021 @ 1:38 pm

A touching story. Thanks for sharing Ken.

May 30, 2021 @ 7:25 am

Thanks for following my blog, Mike. Great to hear from you again.

May 29, 2021 @ 7:01 am

Wow! What a heartwarming, touching and beautiful story. It gets deep into one’s heart, mind and soul. Thank you for sharing this inspiring life experience , Ken Oder!

May 29, 2021 @ 7:25 am

Thanks, Uma! Writing it took me back to those times. Those were difficult days, but we were fortunate and the outcome warmed our hearts, too.

May 29, 2021 @ 2:31 am

Loved this story ~ I knew of John Henry so was happy to know, when I reached his name, WHO this little horse was! And so glad that he brought a bit of fun/joy to you & your son. Happy to know that your son beat the odds ~ just like little John Henry!

May 29, 2021 @ 7:22 am

John Henry was a special horse. There’s so much more I could have written about him, but I didn’t want to make the story so long it would discourage readers. My son and I tried to remember how many of his races we saw in person. We think there were five. He won them all. There’s a statue of John Henry outside Arlington Park in Illinois where he won two major stakes races, the second by a nose. It’s entitled “Against All Odds.” There’s a statue of him at Santa Anita, too. He inspired so many people with his determination.

May 28, 2021 @ 2:29 pm

Such a moving story, Ken, of your vigilance and loving attention. So glad you and your son came out stronger.

May 28, 2021 @ 3:02 pm

Thanks, Gay. We were fortunate.

May 28, 2021 @ 2:26 pm

I loved this remembrance and I am so glad your son is OK today. I always loved horses even though I was about 30 before I ever got on one. My first one was a bad boy priced to sell, but after a few years, I usually rode him bareback with no bridle he was so sweet. They are special creatures, and like dogs, they know who loves them and they know who to throw on the ground.

May 28, 2021 @ 3:01 pm

Thanks, Glenna! I love horses, too. I took up riding at 70. I have four horses now. Haven’t been thrown yet, which means they know how I feel about them, I guess.

May 28, 2021 @ 12:37 pm

I love this story… thanks for sharing?

May 28, 2021 @ 12:56 pm

Thanks, Lesley, for the kind words and for following my blog.

May 28, 2021 @ 10:17 am

You left me in tears! So happy for the successful, healthy outcome. All the best.

May 28, 2021 @ 12:56 pm

Thanks, Lucy. It was a tough time but it taught me what’s important in life.