Lily’s Song

I first saw her in a photograph posted on a website about horses for sale in Southern California. I had bought a little sorrel mare, Marge, and I was in the market for a stablemate when my trainer and good friend, Janet, saw an advertisement on the internet and sent me the link.

I first saw her in a photograph posted on a website about horses for sale in Southern California. I had bought a little sorrel mare, Marge, and I was in the market for a stablemate when my trainer and good friend, Janet, saw an advertisement on the internet and sent me the link.

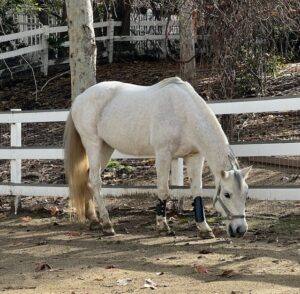

“Gray Azteca mare. 8 years old. Ranch/trail horse. Sound. Takes her leads. Good with children. Location: Lancaster.” In the photograph, she stared at the camera with big, soulful eyes, her ears pricked forward, a dark gray forelock falling over her face.

Janet arranged a meeting with the seller. Lancaster, population 170,000, sits seventy miles north of Los Angeles at the hub of the Antelope Valley in the California High Desert. On a hot dry Sunday afternoon, I pulled off a paved street into a residential neighborhood with sandy dirt roads and small Spanish-style houses on wind-blown, dusty lots.

I parked in front of a pale yellow, tile-roofed home. A short guy in his late thirties wearing a cowboy hat, jeans, and boots, stood on the front stoop. We talked while we waited for Janet. His name was Miguel. He worked as a leadman on an assembly line in one of the aerospace factories that form the backbone of Lancaster’s economy. He bought the horse from a friend when she was two years old. He didn’t have time to work with her anymore because he was busy coaching his sons’ Little League teams. He seemed like a nice guy, a good father trying to raise his kids right.

I parked in front of a pale yellow, tile-roofed home. A short guy in his late thirties wearing a cowboy hat, jeans, and boots, stood on the front stoop. We talked while we waited for Janet. His name was Miguel. He worked as a leadman on an assembly line in one of the aerospace factories that form the backbone of Lancaster’s economy. He bought the horse from a friend when she was two years old. He didn’t have time to work with her anymore because he was busy coaching his sons’ Little League teams. He seemed like a nice guy, a good father trying to raise his kids right.

When Janet got there, we walked around behind the house. A saddled and bridled gray horse stood under a big shady ash tree next to a corral. A chain hooked to her halter and tied to a branch high above her head was pulled taut, forcing her to hold her head tilted upward. Her big eyes watched us as we approached. The look in her eyes and the tension in her stance made me uneasy.

When Janet got there, we walked around behind the house. A saddled and bridled gray horse stood under a big shady ash tree next to a corral. A chain hooked to her halter and tied to a branch high above her head was pulled taut, forcing her to hold her head tilted upward. Her big eyes watched us as we approached. The look in her eyes and the tension in her stance made me uneasy.

Miguel unhooked the chain and led the horse to the corral. When he placed his foot in the stirrup, she crow-hopped and pulled away. The nice guy I’d met on the front stoop disappeared to be replaced by a harsh tyrant, indifferent to the feelings of the horse. He yanked her reins brutally and manhandled her to a standstill to climb in the saddle. In the corral, he forced her through short choppy zig-zag patterns, jerking her head roughly back and forth.

“You don’t need to do that!” Janet shouted. “We’re only looking for a trail horse.”

“You don’t need to do that!” Janet shouted. “We’re only looking for a trail horse.”

Paying no heed to her, Miguel spurred the horse into a top-speed gallop to the corral’s far end, pulled back on her reins so savagely she sat down on her haunches and slid over the sand to come to a stop, then whipped her around, sprinted her back toward us, and viciously muscled her into another sit-down stop, almost ripping her head off in the process.

It was hard to watch.

“You shouldn’t buy this horse,” Janet said to me while Miguel was still out of earshot. “He’s ruined her. She won’t be a safe ride.”

When Miguel dismounted and walked over to us, the nice guy returned. “So, what do you think?” he said, smiling amiably.

The split personality confused me at the time, but since then, I’ve met many horsemen like Miguel, nice people in most aspects of their lives, but with a blind spot about horses. They treat them like inanimate tools with no thoughts, feelings, or emotions, like a tractor or some other type of farm machinery. They expect horses to follow the dictates of their will without the slightest deviation. When a horse resists, they beat her into submission, and when she can no longer perform, they don’t hesitate to put her down.

The split personality confused me at the time, but since then, I’ve met many horsemen like Miguel, nice people in most aspects of their lives, but with a blind spot about horses. They treat them like inanimate tools with no thoughts, feelings, or emotions, like a tractor or some other type of farm machinery. They expect horses to follow the dictates of their will without the slightest deviation. When a horse resists, they beat her into submission, and when she can no longer perform, they don’t hesitate to put her down.

Miguel was such a person. I looked at the horse standing behind him, her head down, trembling, blowing hard. I felt bad for her. “I’d like you to test ride her,” I said to Janet.

Janet gave me a double-take, but she did as I asked, and afterward, when she inspected the horse for soundness, she found that Miguel had bridled her with a spade bit. A spade bit has a wide flat plate that goes over the horse’s tongue and protrudes way up inside its mouth. A skilled rider can use it for maximum control without inflicting pain, but in Miguel’s hands it was an instrument of torture.

Janet exploded and bawled Miguel out. I thought he’d get mad, but his blind spot about horses left him puzzled, rather than offended. He shrugged off her anger and turned to me. “So how about it? Do you want to buy the horse?”

Janet exploded and bawled Miguel out. I thought he’d get mad, but his blind spot about horses left him puzzled, rather than offended. He shrugged off her anger and turned to me. “So how about it? Do you want to buy the horse?”

Janet took me aside. She feels even more strongly about horses than I do, but her job is to protect me and my interests. “He’s abused this horse,” she said. “She may have old injuries we can’t see that didn’t heal properly, and she’s so fearful she won’t be a safe ride for you or your grandchildren.”

I looked over at the horse. Her soulful eyes stared back at me. Something stirred inside my chest. I agreed with Janet’s assessment, but I couldn’t leave her there. “I’d pay double the asking price,” I said, “just to get her away from this guy.”

I looked over at the horse. Her soulful eyes stared back at me. Something stirred inside my chest. I agreed with Janet’s assessment, but I couldn’t leave her there. “I’d pay double the asking price,” I said, “just to get her away from this guy.”

I bought her.

We named her Lily.

Janet was right about old injuries. There are deep scars on her legs. She favors her left shoulder and walks with an inconsistent gait. Janet thinks Miguel showed her in a charreada, or Mexican Rodeo. It’s comprised of nine events, including the manganas, or horse tripping, where a rider on horseback chases a horse around an arena, lassoes her legs, and makes her trip and fall.

Janet was right about old injuries. There are deep scars on her legs. She favors her left shoulder and walks with an inconsistent gait. Janet thinks Miguel showed her in a charreada, or Mexican Rodeo. It’s comprised of nine events, including the manganas, or horse tripping, where a rider on horseback chases a horse around an arena, lassoes her legs, and makes her trip and fall.

Lily’s psychological scars run deep, too. When she arrived in Hidden Hills, she was afraid of me. She shrank from my raised hand and wouldn’t let me touch her. I kept trying, and after a few days, she calmed down enough to let me stroke her neck and rub her back.

Lily’s psychological scars run deep, too. When she arrived in Hidden Hills, she was afraid of me. She shrank from my raised hand and wouldn’t let me touch her. I kept trying, and after a few days, she calmed down enough to let me stroke her neck and rub her back.

On one of my visits with her, I found a small hard knot low on her shoulder and another one higher up. The vet found more of them under her tail. “She has melanoma,” he said. Melanoma tumors are common among gray horses, he told me. Many of them live normal lives without adverse effects, but the tumors can sometimes be fatal, spreading to vital organs, swelling up, and bursting open. “There’s no cure,” he said, “but there’s a vaccine that can slow the tumors’ growth. It’s expensive, and it often doesn’t work. Most people just ignore the condition and hope the horse outlives it.”

On one of my visits with her, I found a small hard knot low on her shoulder and another one higher up. The vet found more of them under her tail. “She has melanoma,” he said. Melanoma tumors are common among gray horses, he told me. Many of them live normal lives without adverse effects, but the tumors can sometimes be fatal, spreading to vital organs, swelling up, and bursting open. “There’s no cure,” he said, “but there’s a vaccine that can slow the tumors’ growth. It’s expensive, and it often doesn’t work. Most people just ignore the condition and hope the horse outlives it.”

We started Lily on the vaccine and scheduled her for injections every six months.

Meanwhile, Janet trained Lily in Hidden Hills’ arenas and on its trails to ease her fears and smooth out her skittishness. Six months passed before she gave me the green light to climb on Lily’s back, and even then, we had to be ponied off a calm, steady gelding for three more months before I could ride her independently.

After all the training, she still gave me some good scares on solo rides. She calmed down over time and I feel safe now when I ride her, but I know fear was burned into her soul with a hot branding iron leaving a scar that can’t ever heal entirely. So, I ride her with vigilance and care, and I’ll never put my grandchildren on her back.

After all the training, she still gave me some good scares on solo rides. She calmed down over time and I feel safe now when I ride her, but I know fear was burned into her soul with a hot branding iron leaving a scar that can’t ever heal entirely. So, I ride her with vigilance and care, and I’ll never put my grandchildren on her back.

Lily’s fourteen now. She’s been with me for six years. The vaccine seems to have helped. Her tumors have grown, but not much, and they haven’t affected her overall health. Psychologically, she’s much better. She accepts affection and gives it in return.

I love my horses and a lot of horses that aren’t mine. They all tug at my heart, but sometimes Lily tugs a little harder. She still startles when I approach her too quickly or raise my hand too suddenly. In those moments, she looks at me the way she did that first time I saw her tied to the tree in Miguel’s backyard, and I know she still remembers Miguel, the charreada, and the magnanas.

I love my horses and a lot of horses that aren’t mine. They all tug at my heart, but sometimes Lily tugs a little harder. She still startles when I approach her too quickly or raise my hand too suddenly. In those moments, she looks at me the way she did that first time I saw her tied to the tree in Miguel’s backyard, and I know she still remembers Miguel, the charreada, and the magnanas.

I wish I could purge the nightmares of Lily’s past from her mind, but I can not. All I can do is keep her safe. And when I see that fearful look in her eyes, I stay longer with her and touch her more gently and try harder to make her feel what’s in my heart.

February 14, 2024 @ 2:20 pm

Hopefully Miguel has no other animals. His little league kids must be close to adults by now. What about all the horror stories we hear about horses in the racing business?

February 15, 2024 @ 7:19 am

Hi Mike, Glad to hear from you. I think Miguel was a good dad, just hard-hearted about horses. A mare and foal were stalled near the corral, but I think (hope) they belonged to his neighbor. And the race horse business should be shut down, or at least very heavily regulated to protect the horses. They push them way too hard.

February 7, 2024 @ 3:52 pm

Ken, You never fail to capture my complete attention, and this was extra special. Lily is a lucky girl — most would not have taken the time or given her the care you have given. Good for you — God is smiling …..

February 8, 2024 @ 7:01 am

Thanks, Danny. Having Lily in my life has been a great gift.

February 5, 2024 @ 5:09 pm

When I received this email, I delayed reading it because (a) your stories always make me emotional and (b) any of your stories about horses remind me of the horses I’ve loved and lost. Lucky Lilly. Lucky you. Thanks for doing that for her.

February 6, 2024 @ 7:18 am

Well, in a different context, someone said it’s better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all. That saying applies to horses, I think. And dogs. Sigh. Lily’s lucky, I hope, but so am I to have her in my life. Thanks for following my blog even though it takes an emotional toll sometimes.

February 6, 2024 @ 2:08 pm

That’s just me Ken. I wouldn’t want to be any other way.

February 5, 2024 @ 4:54 pm

One never regrets doing a good thing! Bless you ! I also rescued a horse ! A retired show horse locked up most of ten years. So much damage

February 6, 2024 @ 7:13 am

Thanks. Glad you saved the show horse.

February 5, 2024 @ 4:26 pm

Great story. You should be a writer. 😁

Lily is a lucky horse.

February 6, 2024 @ 7:12 am

Thanks, Lucian. Maybe I’ll give it a try.

February 5, 2024 @ 10:59 am

This is so beautiful and heartfelt. Reminds me how lucky I am to have gotten to be a lawyer with you all those years ago! xoxox

February 5, 2024 @ 11:56 am

Hey! I was the lucky one! Lucky with Lily. and real lucky with you.

February 5, 2024 @ 4:01 pm

Beautiful! One never regrets doing a good thing. I had six and didn’t need a seventh. I rescued a retired show horse on his way to the sale barn . They called him the outlaw. Locked up most of ten years . He’s a special soul

February 5, 2024 @ 4:14 pm

Thanks, Monika. I’m so glad you saved the outlaw! Janet reminds me every so often that we can’t save all the horses being mistreated. I know she’s right, but I sure wish we could.

February 5, 2024 @ 9:48 am

Wonderful story beuatifullt told.

February 5, 2024 @ 11:55 am

Thanks, Tom!

February 5, 2024 @ 8:55 am

Many children suffer these abuses as well and we wonder why they grow up like they do. It would be a much better world if we had enough Kens in the world to love these wounded animals and humans and help them learn trust, love and kindness. Thank you Ken for all those souls you love

February 5, 2024 @ 9:04 am

Thanks, Mary. We could use a lot more Marys, too.

February 5, 2024 @ 6:58 am

Ken, this is such a beautiful story of love for what God has created. I will never understand the cruelty of some people, but it is persons like you who give me hope for mankind. Thank you for being the person you are!

February 5, 2024 @ 7:08 am

Thanks for the kind words, June. I can’t understand the cruelty either. All we can do is try to make up for it with love and kindness.

February 5, 2024 @ 6:46 am

I know you love her. I get it. And I’ve also met people who think the only way to control a horse is with harsh treatment. I love the smell of horses. I would have been happy being a stable hand.

February 5, 2024 @ 7:06 am

I’ve stumbled upon becoming a stable hand in my dotage, and it’s the best job I’ve ever had. Lily and all horses are a great gift.

February 5, 2024 @ 6:46 am

Love your writing Ken- so keep going!

February 5, 2024 @ 7:03 am

Thanks, Cathy.

February 4, 2024 @ 9:18 am

Beautiful and again you have brought me to tears 🙏♥️Lily is so lucky to have you in her life and so am I

February 4, 2024 @ 11:42 am

I’m lucky to have Lily in my life. And you!

February 3, 2024 @ 7:17 pm

What a loving story about a heartfelt rescue. Lily couldn’t have found a better home. So glad you have each other❣️

February 4, 2024 @ 7:15 am

Thanks, I was lucky to be the one to answer Miguel’s sales ad. She’s brought me so much joy.

February 3, 2024 @ 4:44 pm

You certainly have a heart for that wounded horse! She is extremely fortunate!

February 3, 2024 @ 5:55 pm

I wish I could save all the mistreated horses. They deserve it. And I’m extremely fortunate to have Lily in my life.

February 3, 2024 @ 2:27 pm

She is loving the loving in that picture. She looks sweet and relaxed. I too had a horse that I never let my son ride. He was a one person horse and put my husband in the hospital. He hated men.

February 3, 2024 @ 5:53 pm

Lily was afraid of men when I bought her, but not Janet. She head-butted the vet when he tried to give her a shot, but she let Janet deworm her. Took me a long time to break through Lily’s fear of Miguel and other men. She’s good with me now, though. TLC can work wonders.

February 2, 2024 @ 5:53 pm

Lovely story as always.…she is a lucky girl.

February 3, 2024 @ 8:00 am

Thanks, Cindy. I feel pretty lucky to have her.