The Cancer Club

My interoffice phone line rang. “Hey, Ken. It’s Paul. Can you come up to my office?”

“Sure.”

I climbed the inside fire stairwell from floor 43 to 46 and walked around the tower to Paul’s office. Tall and lean with dark brown hair, he sat at his desk, smoking a cigarette. “Close the door,” he said.

I closed it and sat in a chair across from him, my back to the bank of windows that looked out over LA.

He stubbed out his Marlboro and looked me directly in the eye. “I have cancer.”

I couldn’t process most of what Paul said after that. About all I remember are the words “aggressive” and “late stage.”

I cried.

In 1990, Paul and I were in our early 40’s, and we were attorneys with the law firm, Latham and Watkins. If I had ranked my friends back then, he would have placed in the top ten.

I pulled myself together. “Is there anything I can do?”

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

We talked for a long while about fun times we’d shared. Then he said he had to call the next friend on his list. We hugged. I went back to my office, closed the door, and cried some more.

He was gone in three months. An emotional wreck at the funeral, I got it together long enough to give my condolences to his wife. She told me Paul had treasured our friendship, and the way she said it, I knew it was true. I’ve carried that with me ever since.

Thirty-three years later, I noticed a small mole on my shoulder near my neck.

Because Cindy is fair-skinned and susceptible to melanoma, we follow a regimen of six-month checkups with a dermatologist. At the next exam, I asked him to look at the mole. “It’s nothing to worry about,” he said. His verdict remained the same for two years.

Last spring the mole grew larger and darker. One afternoon in June, my daughter and I were in the pool watching my grandkids. “What’s that on your shoulder?” Chelsea said.

“Just a mole. The doctor says it’s nothing.”

“I don’t know, Dad. It looks bad.”

That night I awoke from a sound sleep at 3 am. My first conscious thought came to me in a clear quiet voice: “Get that mole off your shoulder, or it will kill you.”

It scared me bad. I went to the dermatologist. He again said the mole was harmless.

“I want to take it off,” I said.

He agreed to remove it, gave me a shot, and sliced it off. “There’s dark tissue under the mole,” he said, sounding concerned. He cut into it.

“I only gave you a local. Are you in pain?”

It was killing me. “No pain,” I said.

He cut deeper. “You must be in pain.”

My shoulder was on fire. “I’m fine. Make sure you get all of it.”

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

The dermatologist’s sense of urgency alarmed me. “How bad is this?” I asked.

“Hopefully, we caught it early. If it hasn’t metastasized, you should be all right.”

I hung up the phone and stared at it. The mole had appeared two years ago, but the cancerous tissue under it may not have been there as long. The surgeon will remove it, and I’ll be okay, I thought. I decided not to tell anyone until I knew more.

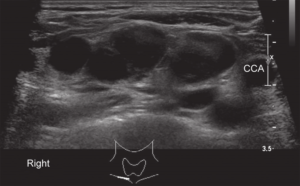

A few days later I met with the surgeon. In his fifties with a full head of gray hair, he told me my form of cancer, melanoma beneath the skin, was rare. It could have taken root in another part of my body and spread to that spot, or if it originated in my shoulder and had been there awhile, it could have spread to other locations. “I need to know if the cancer has metastasized before I operate on your shoulder,” he said. He scheduled a battery of tests over the next six weeks, followed immediately by the shoulder operation.

The surgeon’s diagnosis frightened me. “Could this be fatal?” I asked him.

“Try not to worry,” he said. “We’re very good at what we do.”

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

I got lost driving home. I pulled to the curb, cut the ignition, and took deep breaths.

A couple years earlier, a nice gray-haired lady driving a black Escalade hit me and my grocery cart as I walked from a Ralph’s store through a crosswalk. I wasn’t hurt, but she fell apart, sobbing hysterically. It took her a long time to calm down enough to tell me she’d just been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. I helped her park her Escalade and called her husband.

The Grim Reaper blinded the nice lady that day. Now he squatted on the hood of my truck. I punched my home address into Google Maps and followed the voice commands, crawling along at a turtle-pace in the slow lane.

When I got home, I told Cindy. Positive and supportive as always, she didn’t flinch. “You’re strong! If they find something, you’ll beat it!” My son and daughters said the same. So did my good friend and horseback-riding instructor, Janet. And my riding buddy, Alecia.

Everyone was confident except me. That night in bed in the dark trapped inside my head with the boogeyman, I was certain the cancer had metastasized. I catalogued all the recent symptoms I’d ignored that might be cancer related. Those hard cramps last week, stomach cancer; my aching joints, bone cancer; occasional headaches, brain cancer; severe chest congestion, lung cancer. I imagined various scenes with the surgeon delivering different deadly diagnoses.

Show some courage, I told myself. You’re 77. You’ve lived a long full life. Cancer cut Paul down in his prime, but he faced death bravely. Go out proud and brave, like he did.

I don’t want to go out! I love my life. I want to stay with Cindy, my kids and grandkids, the horses, P.D., my friends. I don’t want to die!

Get a grip. You’re not going to die. You don’t know anything yet. You don’t even know if the cancer has spread.

Yeah, well, I know something is growing inside me right now that could kill me.

And so it went. On and on. All night long.

At dawn, I drove to the barn and went to Lily’s stall. An Azteca gray mare, she has equine melanoma. There is no cure, but it isn’t always fatal. She may live out her life with the cancer or it may kill her, and there’s nothing I can do to influence the outcome. (See Lily’s Song for more about her.)

I groomed her, then stood beside her, looking into her soulful eyes. I placed my forehead against her neck and put my arm over her back. Even if they love you, most horses pull away when you hold them close for too long. That morning, Lily stood still for me. I don’t know if she knew, but it felt like she did.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

In the 1970’s, I taught English Literature to high school seniors. One of them later became the top intellectual property attorney in the nation. Now in retirement, he’d been diagnosed with cancer and was undergoing treatment. “I’m scared crazy,” I wrote to him.

“This ‘not knowing’ stage that you are in might well be the hardest part of the process,” he wrote back. “I hope and pray the cancer has not spread. That is the hope and prayer of all in our club. But if it has spread, to a small or large degree, you are smart and capable and surrounded by a great medical team and family, and you will deal with it as best as you can. That’s all we can do.” His steady guidance through the coming weeks calmed me down and gave me hope.

Meanwhile, my cancer tests went forward. Most of them were familiar to me from previous ailments and some seemed designed only to determine if I was healthy enough to survive surgery, but I agonized over each one, convinced it would discover more cancer. Thankfully, my anxieties went unrealized. One by one, the results came in negative.

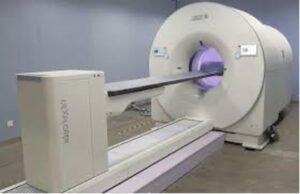

The last test, the big mother of them all, the one I feared most, the PET CT Whole Body scan, came at the end of the six weeks. My daughter, Devon, drove me to COH’s radiology department. They injected me with radioactive fluid, placed me on a gurney, and slowly slid me through a giant donut, capturing internal images of my entire body, starting at my feet and moving up to the top of my head. If there were cancerous tumors inside me, the donut would find them. The technician said the results would come back in three days, just before the shoulder operation.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

I was still frightened by my dream when I got to the barn at dawn. Lily was skittish and flighty, but she calmed down when I stroked her neck and rubbed her ears. I did, too. I stayed with her a long time that morning.

On the day of my operation, they stretched me out on a bed in the nuclear medicine room and injected radioactive fluid into my shoulder to track blood flow to the nearest lymph nodes. For the cancer to spread from my shoulder it would first infect “sentinel” nodes that would carry the cancer elsewhere. The procedure would identify any bad ones the surgeon would need to remove. The technicians worked on me for two hours, then wheeled me down to pre-op.

The surgeon came in. “The Whole Body scan was good,” he said. “It found no cancer anywhere other than in your shoulder.”

Sitting by my bed, my son, Josh, pumped his fist. “Yes!”

If I hadn’t been exhausted, I would have jumped up and cheered.

Now, it all came down to the shoulder surgery and the potentially infected lymph nodes. They rolled me into the operating room, and the anesthesiologist knocked me out.

I awoke in the recovery room with a bandage on my shoulder covering an incision three inches long. I was telling the nurse about Lily when the surgeon came in, smiling. “I got all the cancer. We didn’t take any lymph nodes. They all looked good.”

That was the night of September 9. I’d gotten the best possible results on all the tests; the surgery was successful; and my lymph nodes appeared to be clear. I was elated.

I thought cancer was done with me, but in the post-op meeting, I learned that membership in the cancer club is like the Eagles’ Hotel California. You can check out, but you can never leave.

Cancer is resilient. It might be hiding in clusters of cells too small for the tests to detect, waiting to blossom into new tumors, or it might sprout inexplicably again in a new location, like it did in my shoulder. “We will observe you,” the surgeon said. He ordered a round of tests for next February, including another PET CT Whole Body scan. After that, he plans to slide me through the big donut every six months. If the cancer comes back, the surgeon will find it early to give us the best chance of beating it.

Cancer’s Hotel California is a big place with many rooms. Cancer victims pay a dear price for most of them: chemotherapy, radiation, ablation, immunotherapy, stem cell transplants, hormone therapy, bone marrow transplants. Not me. I got off easy, at least for now. I got the best room in the building, and it cost me almost nothing. No real pain. No significant sacrifice. Just six weeks of worry and the prospect of periodic tests going forward.

Although my little skirmish didn’t require the colossal strength, boundless stamina, and lion-hearted courage so many cancer patients bring to their grueling battles against the disease, it scared me enough to change me forever. It gave me a priceless gift: The realization that each day of my life is precious. Of course, I knew that all along. We all know it. But I know it in a different way now. I know it deep down inside, and I never forget, even for a moment.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.

December 2, 2024 @ 11:13 am

I’m in the Cancer Club too. I’m 74 and just got cleared of lung cancer. I feel your pain. We must be like recovering alcoholics and take one day at a time.

Hugs!

December 2, 2024 @ 1:56 pm

Thank you, Kathleen. I’m glad you are clear of the cancer. You are so right. One day at a time, and enjoying each day to the fullest.

December 2, 2024 @ 9:33 pm

Hi Ken,

Thank you for sharing your story. I have been where you are and I think your friend is right that but the hardest part of the process is when you don’t know what you’re facing. Once you know you can endure whatever the treatments are because you can create a plan and move forward. Chemo and radiation were horrible, but the glimmer of hope that they gave me kept me going. I’m so very grateful you didn’t have to go through that right now but also glad that you reminded all of us to treasure each day we have.

December 3, 2024 @ 7:49 am

Thanks, Ursula. I’m so glad you won your battle. I admire your courage and strength, especially now that I got a glimpse of what it takes to fight through these ordeals. Let’s hope for good outcomes on all future tests for us and the others in the club.

November 30, 2024 @ 7:30 pm

Ken, I’ve been a hospice chaplain for over ten years now and I’ve heard too many of stories similar to yours that went the other way. Cancer is such an insidious enemy and stories like yours hopefully give us all the courage to take the steps to do what needs to be done — to defeat our fears — and to move forward. I had prostate cancer 20 years or so ago, had the surgery and have been cancer free since. But I vividly recall the fear I felt during the diagnosis and treatment stages. Thank you so much for sharing and for speaking into lives and very possibly giving someone the impetus to move forward. Dan

December 1, 2024 @ 7:19 am

I admire your work as a hospice chaplain. You are brave and compassionate. I’m not sure I defeated my fears on this one. I was scared throughout the tests and a piece of me is still anxious about the periodic tests yet to come, but I feel blessed to come through this so easily. Some of our classmates have fought much more difficult battles valiantly, and as I understand it, cancer claimed Anne Stevens’ life. My brush with cancer didn’t require much sacrifice from me, but it gave me a deeper understanding of the major battles so many others have fought and a new appreciation for my blessings. I wrote this to pass those new lessons along. Thanks for all you do for others, Dan!

November 30, 2024 @ 7:27 pm

Ken — WOW! What a brush with the man and roan horse. Your beautifully written piece really struck home. One of my life-long, dear friends lost her first husband in his early thirties because of a misdiagnosed melanoma. He was a wonderful man and very talented lawyer. I’m so very glad you’re on an entirely different path. Very best to you and Cindy from both Jack and me.

December 1, 2024 @ 7:10 am

Thanks, Belinda. I’m sorry for the loss of your friend’s first husband. I was angry at first at my dermatologist for having allowed that mole to remain on my shoulder for two years, but the surgeon made clear to me that the dermatologist’s diagnosis of the mole was correct. It was not cancerous. “That mole was the best thing that ever happened to you,” he said. If it hadn’t grown in that spot and yu hadn’t removed it, the cancer would have remained below the skin and would not have been discovered it until it metastasized to other organs. I was very lucky! Best to you and Jack, too.

November 30, 2024 @ 9:00 am

Hi Ken Oder. I have vivid memories of Paul Van Arsdale, who was in charge of firm collections at the time he was diagnosed. I called his office one day and was told he was sick, and then he was gone so quickly. I’ve also had two brushes with skin cancer, melanoma and squamous, and it was my daughter’s prompting to get a mole checked that caught them. Keep writing!

November 30, 2024 @ 2:33 pm

Sounds like we have a mole, a concerned daughter, and melanoma in common. Quite a coincidence. Thanks for the encouragement, Chris. I plan to keep writing now that I’m going to be around for a while longer.

November 30, 2024 @ 8:58 am

I remember Paul’s funeral. That was a rough week. Glad you’re still standing. Fortunately/unfortunately, I’m way too familiar with CoH. Let’s catch up some time.

November 30, 2024 @ 2:31 pm

It was hard to lose Paul. I had heard you checked into Cancer’s Hotel California a few years ago. You are doing well now, I hope. COH is a wonderful place. I would love to catch up with you. Drop me a line on the whippoorwillhollow gmail address when you get a chance.

November 30, 2024 @ 8:53 am

Ken,

Your journey was well understood by me! In late 2013, I was diagnosed with desmoplastic squamous cell carcinoma on my head. After significant surgery and lengthy follow-ups, my experience has fortunately been similar to yours.

Eleven plus years following my first surgery, your analogy of still being checked in to ‘Hotel California’ however, is spot on!

God bless!

Gary

November 30, 2024 @ 2:27 pm

Thanks for sharing that, Gary. I have a friend who contracted cancer on the outside of his skull near the top of his head. He, too, came through it okay and is still clear. These are harrowing experiences I don’t believe people can fully understand until they’ve gone through it.

November 30, 2024 @ 6:30 am

Thanks for the great story. I’ve not had any issues but my wife is fair skinned and has had cancerous spots removed. We both see the dermatologist on a regular basis — her every 6 months and me annually.

November 30, 2024 @ 6:49 am

Thanks, Randy. We’ve both had cancerous spots removed in the past. Apparently, most of those aren’t aggressive aslong as you catch them soon enough. The melanoma strain I had was beneath the skin and aggressive. The surgeon told me it was extremely rare. He sees about five cases of melanoma a week. but only about one per year under the skin. That mole and my daughter tipped me off so I was fortunate to get it out early. Those checkups are really important.

November 30, 2024 @ 1:18 am

Happy for you and all of us who love you including PD and the horses

🙏🐴🐴🐴🐴🐴🐶

November 30, 2024 @ 6:44 am

Thanks for all the support through this little ordeal. Your sympathy and encouragement powered me through it.

November 29, 2024 @ 7:24 pm

So glad your results have been good. I pray they will continue in this manner.

November 30, 2024 @ 6:43 am

Thanks, Pat. I appreciate the good wishes. I’ve been very fortunate.

November 29, 2024 @ 4:25 pm

This is wonderfully written. So sorry I never was housed in LA Office and gotten to know you better. However, I was always was able to to appreciate you and your accomplishments. You’re remarkable and a guidepost for us all.

November 30, 2024 @ 6:41 am

Thanks, Mike, for the kind words. I’ve enjoyed following your comments on Facebook. It would have been my gain if we had gotten to know each other better at Latham. I admire you and your accomplishments greatly,

November 29, 2024 @ 4:23 pm

So very glad you didn’t wait and that things are going well for now. Also loving your resolve and commitment to cherishing all the joys you have. ❤️❤️❤️

November 30, 2024 @ 6:50 am

Thanks, Sonja. I’m very fortunate the mole and Chelsea made me go to the doctor so he caught it early. Just glad to be here!

November 29, 2024 @ 3:45 pm

As usual, a beautifully told story, and I’m so glad for the happy ending! Thank you for sharing and I know it will remind people to check these things out for sure!

November 29, 2024 @ 4:24 pm

The surgeon tells me if it hadn’t been for that mole and Chelsea lighting a fire under me to take it off, the bad cells would have continued to grow under there and I never would have known. I’ve experienced some good strokes of luck in my life, but that mole was the best thing that ever happened to me.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:52 pm

Ken — so glad to hear the outcome of this powerful story. Another health-protective option that seems to hold promise is the ExThera blood filter, first developed as a broad-spectrum defense against pathogens (e.g., Covid), but now showing some significant potential value in strengthening the body’s immune system to fit cancers. It’s still early stage but the results are quite good. I’m glad you shared your predicament with our mutual friend from your Virginia teaching days. He’s a gem, as are you. I’m glad you have Lily there as your buddy. Take care.

November 29, 2024 @ 4:22 pm

I can’t tell you how much it has meant to me to reconnect with Mike. He and I have kept up a running email correspondence since you put us together on that Zoom call. His friendship and good counsel means the world to me, and on this crisis his advice is what kept me sane. His last tests cleared him of cancer, by the way, and he came through unscathed, as have I so far.

I had not heard of the ExThera blood filter. It sounds wonderful. I’ll look into it.

Come out and see Lily and me again when you get the chance.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:16 pm

Glad it worked out, Ken. I went through a similar experience in’77…stage 4 melanoma on the neck. After the initial radical surgery (some of your tests were not available then) I have never had a recurrence. I can attest that a positive fighting mindset is crucial moving forward. As you say, enjoy every day for the gift that it is.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:34 pm

Thanks for sharing that, John. You’re the second person I’ve met who experienced melanoma of this type, got it removed, and experienced no recurrence. I’m glad that’s how it worked out for you and that’s what I’m hoping for, too.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:03 pm

Wow. Ken, I’m certainly elated that the cancer has not spread. It was signigicant that you had the “dream” that you needed that mole removed. God is with you always.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:31 pm

That dream was prompted by my daughter’s warning that day, I think. They both lit a fire under me and I’m so glad they did. I have been given many blessings in my life and the red alerts on this one kept the string going.

November 29, 2024 @ 12:53 pm

So very glad you are well and enjoying your family, friends and delightful pets.

I look forward to many more of your great stories.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:28 pm

Thanks, Sharon. I’m very lucky.

November 29, 2024 @ 11:44 am

Ken. Good to know you won this round. Imagine this to have occurred back in UVa days. Our machines are so much better now! Of course being 77 too I hope they leave me alone! I had a melanoma 11 years ago after moving to Fla and realizing li need a bit of a tan. Fortunately my blond wife regularly saw the dermatologist and he found snd excised mine. Then 6 years ago my Apple Watch told me to see the cardiologist and 3 weeks later had a quadruple! Guess I’ll keep that machine on my wrist forever did 50 on my Trek yesterday so clearly that one worked well.

November 29, 2024 @ 1:28 pm

Hi Chad, Great to hear from you again. Sounds like that Apple Watch saved your life. I’ve heard several similar stories. About time I got one of my own. I’m staying active, too. Everything I’ve read recommends good exercise as the best preventive medicine we can Take.

November 29, 2024 @ 5:49 pm

My cardiologist (after the repair job) said to use it or lose it!

November 30, 2024 @ 6:42 am

He’s right about that. Let’s keep on using it!

November 29, 2024 @ 10:56 am

Ken Thanks for sharing your story with me.I have lost quite a few family members over the years and think of them often.So glad your daughter lite a fire under you to get it removed.I am 73 now and know life gets shorter each year now.I had never thought much about it until I hit my 70s.My Grandfather and father both died with pancreas cancer one at 72 the other at 73.Its always in the back of my mind being 73 now.Life is good so just enjoy each day as much as you can.

November 29, 2024 @ 11:03 am

That’s the lesson I learned, Larry. Each day is precious. I don’t know why the medical system doesn’t give everybody our age those Whole Body PET scans. It’s the best way to catch this stuff early. Stay healthy and enjoy our golden years!

November 29, 2024 @ 10:45 am

Great story Ken!

November 29, 2024 @ 11:01 am

Thanks, Mike. I got lucky.

November 29, 2024 @ 10:30 am

I had to scroll right to the end before going back to read this. I held my breath. So relieved. Carpe diem and don’t be stranger. Let’s pick a day for lunch near your place.

November 29, 2024 @ 11:00 am

Hey, we need to have that lunch. No time to waste. You never know what the future might bring to screw us up! I’ll send you some dates via email.