Vin Scully

Tuesday night, August 2, lying in bed in his Hidden Hills home, Vin Scully, the legendary sportscaster, drew his last breath.

Tuesday night, August 2, lying in bed in his Hidden Hills home, Vin Scully, the legendary sportscaster, drew his last breath.

Cindy and I live across the street from him. I was in my home office when he passed. About 9:00 p.m. I found the news of his death on the Hidden Hills Facebook page. A neighbor two doors down posted, “Rest In Peace Vin Scully. Without question the greatest sports broadcaster and simply awesome neighbor. Huge loss to Hidden Hills and fans alike. Always willing to talk at the mailbox. Always made you feel like this was going to be the year we won it all.”

I stared at that post for a long time.

His passing was not a surprise. He was 94 and had been in failing health. A while back, the red and blue lights of emergency vehicles flashed in our front windows when he fell and broke his hip. Publicly, he made light of it. “I won’t be doing anymore headfirst sliding,” he quipped to a reporter, but it was a serious injury.

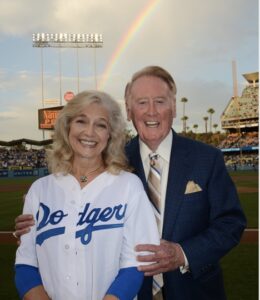

A few months later, his wife Sandi died after a long battle with Lou Gehrig’s disease. Scully was no stranger to grief. He lost his first wife in 1972 to a prescription drug overdose and a son, Michael, in 1994 in a helicopter crash, but Sandi had been his constant companion for almost 50 years and her passing hit him hard.

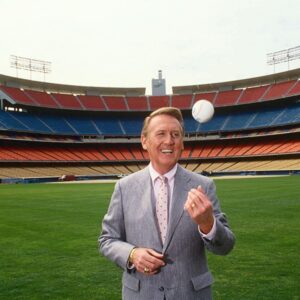

The Sunday before his death, when we saw family members gathering at his home, we anticipated bad news. Despite that, when it came, I had a hard time assimilating it. His smooth voice had been a steady presence in LA since I moved here in 1975. He broadcast Dodgers games for 67 years, starting in 1953 in Brooklyn, following the Dodgers to LA in 1958, then calling almost every game here until he stepped away from the microphone at the end of the 2016 season at the age of 88.

He was a living legend. He was voted national sportscaster of the year 4 times, California sportscaster of the year 33 times, sportscaster of the twentieth century, and the top-ranked sportscaster of all time. He received a Lifetime Emmy Award. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He was inducted into the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame, the NAB Broadcasters Hall of Fame, the National Radio Hall of Fame, the California Sports Hall of Fame, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In LA Straw polls we voted him the most trusted media personality, the most memorable person in Dodger history, and the biggest icon in LA sports history.

He was a living legend. He was voted national sportscaster of the year 4 times, California sportscaster of the year 33 times, sportscaster of the twentieth century, and the top-ranked sportscaster of all time. He received a Lifetime Emmy Award. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He was inducted into the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame, the NAB Broadcasters Hall of Fame, the National Radio Hall of Fame, the California Sports Hall of Fame, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In LA Straw polls we voted him the most trusted media personality, the most memorable person in Dodger history, and the biggest icon in LA sports history.

When I moved to LA, I’d never heard of Vin Scully. My law firm represented the Dodgers. One of my first legal assignments was to draft a contract for the team. My supervising attorney called me into his office and handed me a file entitled Vin Scully.

“Who’s Vin Scully?” I asked.

“Who’s Vin Scully?” I asked.

He paused. “Where are you from?”

“Virginia.”

“I take it you crawled out of the Great Dismal Swamp only recently.”

He gave me a good-natured tutorial on Vin Scully’s central role in the storied history of Dodger baseball. We drafted a short contract in plain, straightforward language, the kind that depends on trust, good faith, and integrity, and the Dodgers privately sealed the deal with him without rancor, bitterness, or brinksmanship.

Watching Dodgers telecasts my first summer in LA, I understood why the organization held him in such high regard. The way he addressed his audience was different from any sportscaster I’d ever listened to. It was as though a well-read, unpretentious, nice guy sauntered into my living room and pulled up a chair beside me. He talked easily about the game, mixing in vignettes about the players, coaches, and umpires, stories about life’s lessons, and sometimes bits and pieces of history, literature, art, and culture.

Among the constellation of his masterpiece broadcasts, some of the shiniest stars were his performances during the biggest moments in baseball history. Like no other announcer, he understood the virtue of silence. At the peak of the excitement, while the crowd roared, he kept quiet, allowing the audience to drink it all in. Then, when we’d finally caught our breath, his first words perfectly captured the drama and significance of the moment.

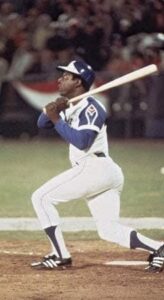

Two of these high points are indelibly etched in my memory. In 1974 Hank Aaron hit his record-breaking 715th career home run in Atlanta against the Dodgers. “To the fence. It’s gone,” Scully said, then fell silent. The crowd cheered as Aaron rounded the bases and was mobbed at home plate. After 31 seconds of silence, a lifetime in broadcasting, he reclaimed the mic. “What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world. A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the deep South for breaking a record of an all-time baseball idol.”

In the first game of the 1988 World Series, Kirk Gibson hobbled to the plate on crippled legs when the Dodgers were down to their last out and miraculously hit a game-winning walk-off home run. Scully’s call: “High fly ball into right field. She is gone.” He said nothing more for an incredible one minute and eight seconds as virtually everyone in LA went wild. Then he expressed what we all felt in our hearts. “In a year that has been so improbable, the impossible has happened.”

He spoke in perfect sentences with flawless grammar while still somehow preserving an informal familiarity and casual intimacy with his listeners, and most amazingly, he made it up as he went along. Baseball games don’t follow a script. Scully broadcast each game as it unfolded in front of him with words no one could have written any better beforehand.

When we moved into Hidden Hills, I installed a second telephone line for business calls. The first time I answered its ring, a woman was in mid-conversation about a personal problem. When she paused, a man’s smooth tenor voice broke in, concerned, supportive, encouraging. I immediately recognized the speaker. He had talked to me for three decades.

When we moved into Hidden Hills, I installed a second telephone line for business calls. The first time I answered its ring, a woman was in mid-conversation about a personal problem. When she paused, a man’s smooth tenor voice broke in, concerned, supportive, encouraging. I immediately recognized the speaker. He had talked to me for three decades.

“Mister Scully,” I said nervously, but he and the woman couldn’t hear me. I hung up, not sure what to do. I picked up the line. They were still talking. I called AT&T on my primary line and told a customer service lady my telephone line was tapping Vin Scully’s phone. “I’m talking about THE Vin Scully,” I said.

“Who’s Vin Scully?” she said.

I paused. “Where are you from?”

“Dallas.”

“Is there a swamp in Dallas?”

AT&T sent out a big mean-looking guy with a sour disposition, who turned into a little kid with wide eyes and a shy grin when I told him Vin Scully owned the phone line he’d been assigned to repair.

AT&T sent out a big mean-looking guy with a sour disposition, who turned into a little kid with wide eyes and a shy grin when I told him Vin Scully owned the phone line he’d been assigned to repair.

The first time I saw Vin Scully face-to-face was at Hidden Hills City Hall, our local polling place. He walked in when I was voting. The ancient lady handing out ballots said, “Hey, who’s that handsome red-headed fella?” The elderly woman poll-worker sitting beside her said, “Oh, he’s not much. I heard he sells peanuts for the Dodgers.” They both cackled, then flirted with him mercilessly while they set him up to vote. He was a good sport, laughing and joking through it all.

Not long after that, my dog Zoey and I walked by his house when he came out to the car to head to Dodger stadium to broadcast a night game. He spoke to me and patted Zoey on the head. I was tongue-tied in his presence. “Good luck at the game,” I stammered.

That was stupid, I thought, as I watched his car drive away. I had just wished the greatest sportscaster of all time good luck in broadcasting a mundane regular-season game.

As our neighbor remarked the night of his death, he was always willing to talk at the mailbox. He always greeted me and Zoey on our dog-walks with a warm smile, and his friendliness eventually disarmed my reticence.

As our neighbor remarked the night of his death, he was always willing to talk at the mailbox. He always greeted me and Zoey on our dog-walks with a warm smile, and his friendliness eventually disarmed my reticence.

In a makeshift shrine outside Dodger stadium after Vin Scully’s death, a fan framed a placard that said, “God acquires Vin Scully from the Los Angeles Dodgers.” God broke a lot of hearts the night of August 2. In a letter to the LA Times, a man from Santa Monica said it best. “Little boys are crying all over Los Angeles. They just happen to be 60, 70, and 80 years old.”

He is irreplaceable. For almost seven decades, in our cars, living rooms, and bedrooms, at our kitchen counters and barbecue grills, beside our swimming pools on sunny summer days, he talked to us in an easy way like an old friend.

He is irreplaceable. For almost seven decades, in our cars, living rooms, and bedrooms, at our kitchen counters and barbecue grills, beside our swimming pools on sunny summer days, he talked to us in an easy way like an old friend.

There never has been, and there never will be again, a sportscaster as great or as beloved as Vin Scully.

August 17, 2022 @ 6:05 pm

Wow! Even in the death of such a marvelous man, you have a way of bringing things to life. No obit could ever be more appropriate.

August 19, 2022 @ 8:23 am

Thank you, Dan. He was such a great man it was easy to write a tribute to him.

August 15, 2022 @ 2:53 pm

As always a great post, and a good commentary about a good man.

August 15, 2022 @ 4:07 pm

Thanks, Rebecca!

August 15, 2022 @ 8:02 am

Ken,

Thanks….You put who Vin Scully was into such wonderful words. I shared with many friends!

Regards,

Dick Goodspeed

August 15, 2022 @ 8:11 am

Great to hear from you, Dick. Thanks for following my blog and sharing that piece with your friends. Vin Scully was a great treasure.

Hope all is well with you and family.

August 13, 2022 @ 8:50 am

Tears in my eyes, again, Ken. A beautiful tribute.

August 13, 2022 @ 9:17 am

Thank you, Gay.

August 12, 2022 @ 6:17 pm

Another beautiful piece from the heart. Thank you.

August 12, 2022 @ 7:01 pm

Thanks, Jon.

August 12, 2022 @ 3:18 pm

Ken,

You’ve written a lovely tribute worthy of Vin Scully himself. I love the sentence about the little boys crying over his death even though those little boys were 60, 70, and 80 years old. We do have a swamp or two in Houston fed by our many bayous, but I do remember watching the amazing Hank Aaron record-breaking home run on television and how wise Mr. Scully was to give the fans enough commentary silence to take in the historic moment.

August 12, 2022 @ 3:36 pm

Thanks, Carla. With all that humidity, I figured there had to be a swamp out there somewhere. I saw Hank Aaron’s 715th homer but I was watching on the east coast and Scully wasn’t broadcast back there often in those days. I heard him for the first time when I moved to LA. But my son and I watched the Kirk Gibson homer in my living room. He took a stratospheric moment to a higher level.

August 12, 2022 @ 12:07 pm

Ken,

Having lived in LA for many years, and a Dodger fan, and I had the great opportunity to enjoy many games at “Chavez Ravine” with my son (who bleeds Dodger Blue still today). This article was special and poignant to me!

Thanks!

August 12, 2022 @ 1:12 pm

Thanks, Gary. I didn’t know you lived here. We may have sat in the stadium together in those days before we knew each other. I had 1/4 of a season ticket for two seats for many years. My son and I sat in the blue section way above home plate for many games as he grew up. Vin Scully called all those games. We still go to at least one game a year together to bring back the old times. The next one is in two weeks. We’ll miss him so much.

August 12, 2022 @ 11:39 am

Wow, you left me in tears. I needed this after being so down about the state of our country which I felt is filled with idiots and scumbags. Thanks for Vin Scully.

August 12, 2022 @ 1:04 pm

I shed tears when he passed and again when I wrote this. In addition to the many gifts he gave us that I tried to express in this piece, he was also an antidote to our troubled times, a truly decent human being.

August 12, 2022 @ 11:17 am

Ken,

This is a great piece on Vin Scully. I started as a Brooklyn Dodger fan in the 1950s and my allegiance followed the team out West. Vin Scully was sui generous.

From an old Latham guy.

Bob Greenspon.

August 12, 2022 @ 1:01 pm

Greta to hear from you, Bob! He was definitely one of a kind. The best kind.

August 12, 2022 @ 10:14 am

Ken, a great note on the passing of Vince Scully. I grew up listening to his voice every summer and will miss him dearly. The new broadcasters aren’t even close to his brilliance which is probably a sign of the times. Hope all is well and keep sending your stories. Best, Jim

August 12, 2022 @ 1:00 pm

Thanks, Jim. The first game I heard him broadcast was after I moved here in 1975. It was just an average performance for him, but it blew me away.

August 13, 2022 @ 10:35 am

Been a Dodger fan since the ’50’s and I remember Vin Scully well. In those days, we only had a radio but it didn’t matter. We had Vin. This was a great tribute to Vin, not just a sportscaster, the voice of the Dodgers, but as you pointed out, a decent man, a gentleman with a good sense of humor, a friendly neighbor … so many positive qualities, a welcomed addition to all the heavenly baseball games.

August 13, 2022 @ 12:21 pm

You said it all so well. Sometimes I think listening to him call a game on a radio was better than watching the game. That alone says volumes about how unique he was. After his retirement, when the Dodgers called upon him to throw out a first pitch at a game, he said Duke Snider, Jackie Robinson, Pee Wee Reese and the others had to be laughing their heads off up in heaven to see him on a pitching mound. It’s a little bit of a consolation to think they’re welcoming him to his new ball club now.