Staying Alive at 75

I turned 75 this month.

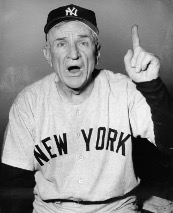

When Casey Stengel was 75, he said, “Most of the people my age is dead. You can look it up.” I did. He was right. In 1965 when he made that statement the average age of death in the U.S. was 70. For men it was 67.

I was surprised to find that Casey’s pronouncement comes close to holding true today. Even with all the advances in healthcare, the average age of death for U.S. men is now only 76.

That doesn’t give me much breathing room, so to speak, but at least I’m still alive on that mortality table. Using an actuarial analysis focusing solely on the life expectancy of men born in 1947, I’m already dead. I passed away in 2012 when I was 65. Fortunately, I didn’t notice.

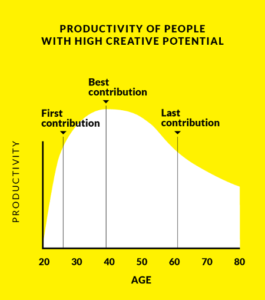

Researching perspectives on aging for this post, I found an article even more troubling than the death charts. In “Why I Hope to Die at 75,” Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel asserts that the optimum age to die is the three-quarter-century mark. He says our healthcare system has succeeded in finding ways to extend life but has failed to delay the onset of disabilities and disease. We live longer only to suffer longer. At 75 he believes most people are headed into a steep physical and cognitive decline, rendering them incapable of making valuable contributions to society. “(F)eeble, ineffectual, and pathetic,” they inflict a crushing financial and emotional burden on their kids and grandkids. To spare himself and everyone else the misery of his descent into infirmity, he intends to commit a passive suicide by rejecting preventive healthcare measures and life-saving procedures after his 75th birthday.

Dr. Emanuel’s credentials make it difficult to dismiss his dour view of aging. An internationally renowned oncologist and bioethicist, he is the University of Pennsylvania’s Vice Provost, Chair of its Medical Ethics and Health Policy Department, was an architect of Obamacare, and currently serves as a senior adviser to the Biden administration on Covid-19.

Dr. Emanuel’s credentials make it difficult to dismiss his dour view of aging. An internationally renowned oncologist and bioethicist, he is the University of Pennsylvania’s Vice Provost, Chair of its Medical Ethics and Health Policy Department, was an architect of Obamacare, and currently serves as a senior adviser to the Biden administration on Covid-19.

He also seems to be a good guy with a loving family and a lot to live for. He was 57 when he wrote his article. He’ll turn 65 this fall, so I hoped growing older might change his opinion about life after 75.

It did not. In a recent interview, he held fast to his original premise, and when questioned about examples of people who are mentally and physically capable and productive well past 75, he discounted their contributions. Such “outliers” are “a very small number,” he said, “and when I look at what those people ‘do,’ almost all of it is what I classify as play … They’re riding motorcycles; they’re hiking … that’s not a meaningful life.”

Not a meaningful life.

Three days before Christmas five years ago, I woke up in the middle of the night with a searing pain in the upper right quadrant of my abdomen beneath the ribcage. It spread upward to my shoulder and became so intense I had to stretch out on the floor on my back with my arms over my head to breathe. I pushed through the pain, and it went away at sunrise.

“It was no big deal,” I told Cindy.

“Call the doctor,” she said. “Now.”

When she uses her steely tone of voice, I do what I’m told. I slunk into the doctor’s office that afternoon. He said my symptoms indicated a gall bladder infection, a common problem, easily treatable. He ordered an ultrasound to confirm his diagnosis.

I lay on my back while a technician moved a hand-held transducer over my abdomen and chest, up, down, and across. The doctor said the ultrasound would take fifteen minutes. The technician kept at it for an hour.

The doctor called me at eight-thirty that night, well past his quitting time. “You have a gall bladder infection,” he said, “but not the normal type. The ultrasound indicates you have Acalculous Cholecystitis.” He said I had to see a gastrointestinal surgeon the next day.

“On Christmas Eve?” I said, alarmed. “How serious is this?”

“It requires immediate attention.”

I pressed him. Reluctantly, he disclosed the fatality rate for this condition as 30 to 50 percent.

I didn’t sleep that night.

The gastrointestinal surgeon, a middle-aged sandy-haired guy with a big nose and wide mouth, was skeptical of the ultrasound. Acalculous Cholecystitis usually attacks people suffering from another serious disease, cancer or heart failure. I had no other illness. He ordered more tests.

Strapped to a gurney in the hospital’s nuclear medicine department for three hours, I watched streams of multicolored fluids on a monitor above me as they coursed through my digestive system. The test results confirmed the ultrasound’s diagnosis.

They wheeled me into the operating room at five o’clock on Christmas Eve. An anesthesiologist, a tall balding man with a reassuring smile, pumped the contents of a syringe into my I.V. “Here comes the good stuff,” he said.

My last thought as the lights dimmed was a drug-blunted fear that I might not wake up.

I was under for two hours.

A spindly crack in an off-white ceiling came into focus. I heard tapping beside me. I looked over to see a heavy-set young orderly dressed in hospital blues working at a computer. He looked up. “You’re back,” he said.

“How do you feel, Dad?”

I turned to see my son standing beside my bed.

Behind him sitting at a desk by the wall, my surgeon gave me thumbs up. “Your gall bladder was gangrenous,” he said. “I got it all.”

I sobbed. “Thanks for saving my life,” I choked out.

“It’s the drugs,” the orderly told my son. “Makes them emotional.”

It wasn’t the drugs. It was the stupendous joy of being alive.

A week later, the results of my gall bladder’s biopsy came back. They found an infinitesimally small gallstone buried in the gangrenous tissue. All the tests had missed it. It had caused the infection. The diagnosis had been wrong from the start. I never had Acalculous Cholecystitis. I had a normal gall bladder infection. The only way it could have killed me was if I had refused to undergo the surgery to remove it.

A week later, the results of my gall bladder’s biopsy came back. They found an infinitesimally small gallstone buried in the gangrenous tissue. All the tests had missed it. It had caused the infection. The diagnosis had been wrong from the start. I never had Acalculous Cholecystitis. I had a normal gall bladder infection. The only way it could have killed me was if I had refused to undergo the surgery to remove it.

I’m glad I didn’t know that at the time. Thinking I might die gave me an appreciation for the blessings that were to come in the days still ahead of me. If I hadn’t survived the infection, here’s some of what I would have missed.

Granddaughter number 1 blossoming into one of the top fifty soccer players in the nation in her age group. Granddaughter number 2, also an elite soccer player, standing at the front of her fifth-grade classroom on grandparents’ day, telling everyone about fun times with Papaw. Granddaughter number 3 falling in love with horses at three years old and becoming an expert rider at seven. Grandson number 1’s precocious talents as a karate warrior, skateboarder, railroad enthusiast, and studio artist. The births of grandsons 2 and 3, both wild and crazy guys now three years old, one a future offensive lineman for the LA Rams, the other destined to become a world-class heavy-equipment operator.

I would have missed building a horse barn, taking up horseback riding, bonding with Marge, Lily, Wilson, and Jackson, and the equine therapy of a thousand trail rides.

I would have missed the heart-swelling exhilaration and quiet satisfaction of crafting the plot and character interplay in The Judas Murders, the celebration of youthful first love in The Princess of Sugar Valley, and the cathartic self-realizations in Keeping the Promise and 20 more blog posts since its publication.

I would have missed watching my younger daughter marry and build a happy family with the love of her life, my son’s careful expansion of his prosperous business without skipping a beat in his role as a loving father and husband, and my older daughter and her husband achieving international acclaim and commercial success for their art gallery.

I would have missed watching my younger daughter marry and build a happy family with the love of her life, my son’s careful expansion of his prosperous business without skipping a beat in his role as a loving father and husband, and my older daughter and her husband achieving international acclaim and commercial success for their art gallery.

I would have missed five more years of love and companionship with Cindy along with the chance to become her caregiver and coach through two years of painful recoveries from double knee replacements, a small installment on my great debt to her for fifty-three years of support and encouragement, propping me up and keeping me going through good times and bad.

This is the short list. The full list of what I would have missed in the past five years would fill more pages than all my novels combined.

I don’t consider my life meaningless. In many ways, it’s more meaningful today than ever before.

I won’t reject preventive healthcare measures and life-saving procedures now that I’m 75. I’ll take all I can get. Dr. Emanuel is a really smart guy, but on the subject of aging, I prefer the medical advice of the poet: “Do not go gentle into that good night,/Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

I could go on about the many gifts of growing older, but I’ll rein it in for your sake and close by updating words I wrote in this blog five years ago.

I’m 75 years old; I’ve lived a long full life; I’ve still got a good ways to go; and you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

August 6, 2022 @ 8:33 am

I often ponder that poem, “…rage against the dying light.” Your words are an encouragement and a wonder. Yes, please continue.

August 7, 2022 @ 8:45 am

Thanks, Rebecca. Let’s both continue writing.

July 31, 2022 @ 8:29 pm

Love this post. Love your gratitude. And what you add in things to be grateful for to the lives of your loved ones. Appreciating nature and life and family and love IS living. By his standard, some people have never deserved health care and to keep living because they don’t “contribute” at the level he means. Yet do their lives not have value, does life not have value to them? Keep on keeping on. We all want you around!!!

August 1, 2022 @ 8:25 am

Thanks, Pamela. Dr. Emanuel seems to think contributing to society is required to lead a meaningful life, but his definitions of contribution, society, and meaningful seem very narrow to me. I think most of us contribute in different ways. Anyway, I plan on hanging around, worthless or not! Thanks for the vote of confidence!

July 31, 2022 @ 7:08 am

Another great post, Ken. What Dr. Emanuel missed is “Gratitude.” We have so much to be grateful for, as you point out over and over again. No need to put a limit on age when you have a loving family and friends, had or still have, a good career, relatively good health, and much more that puts meaning in your life. So what if you are “just playing” after 75? Why shouldn’t you enjoy your life after years of working and raising a family. Keep on going Ken, we are right behind you.

July 31, 2022 @ 9:34 am

Your twitchy woman blog proves my point. All the people you’ve touched in a positive way with your blog and all your activities makes for a meaningful life, maybe even more meaningful than before. We’re all engaged in some “play” as we grow older, I guess, but Dr. Emanuel overlooks the profound contributions so many are making at this age. We’re still in the game in a big way, but our role is different. Your blog is still my gold standard! I strive with every post to emulate it. Keep up the great work!

July 30, 2022 @ 5:30 pm

I think that only when you finally get around to executing your medical directives, do you really consider that the powers of the medical field can keep your body “alive” for longer than you would like. Both Charlie and I finally took that step and decided that as long as we could live without the constant support of machines, we would look forward to whatever

God intended for our lives. Since I am now 75 and 27/365, I look forward to each day and look for the positive things that happen in my life.

Yesterday I enjoyed spending the day with a dear friend who has taught me to live one day at a time! She will celebrate her 101st birthday this month!. She has never driven a car, still lives alone at home, and cooks a meal for her nephew once a week. She has support from friends and family, but essentially gets along fine alone. I could not believe how she devoured the crabs that I picked up for us to eat to celebrate an early birthday.

There is no question about whether I agree with the doctor you wrote about.

I do NOT! But I can agree that there is a time when we need to let go and let God decide the outcome.

Thanks for the thought-provoking writing that you bless us with each time to share!

July 31, 2022 @ 9:25 am

Thanks, Betty Lou, for your comment, insightful as always. I just got around to drafting our advance directives last month and I agree that it focuses the mind on life-prolonging procedures that may not benefit anyone. My parents both lived longer than they wanted. Their last few months they were bedridden and not present. For their sakes, I wish they could have gone a little sooner. I want to rage against the dying of the light, but I realize there can come a time when you can’t see the light anymore and there’s no way to turn it back on. The story of your 101 year old friend is inspiring and captures what I was trying to say in this piece. Giving up makes no sense as long as there is a possibility of blessings ahead.

July 30, 2022 @ 1:48 pm

Great article Ken. I have 4 1/2 years to go before I hit 75 but have no intention of throwing in the towel at that time. I wonder how the good doctor defines “valuable contribution” to society? I work with one charity where 25% of the members are 75 or older. Do they have a few more aches and pains than they did 10 years ago? Of course. But they are still out there working hard to provide for underserved communities. The president of the United States is 79. I wonder if Dr. E,anuel would propose age limits for public service. Where in his thinking is the recognition that wisdom cam come with experience and age? I may not be as quick as I once was- but I am still as feisty. I believe I am contributing more to society now than I ever did in the past.

July 30, 2022 @ 3:30 pm

You know, that’s the irony of the doctor’s viewpoint. I feel my years as a lawyer and an executive were meaningful, but much more self-absorbed, striving to advance my career, make money for my family, and make a good home for us. I feel much more other-directed since I retired, and under any reasonable definition, my life has more meaning to me and the people around me now than ever before. I have a ton of friends who turned 75 this year or are older (high school and college classmates, Safeway contacts, Latham alum, neighborhood friends) and friends like you, who are destined to join the 75 club over the next few years, and they’re all leading very meaningful lives. Doctor Emanuel is a smart guy, but he’s flat wrong about this.

July 30, 2022 @ 6:13 am

Here hear, Ken! Thanks for sharing again, bringing our thoughts and concerns on the subject of aging. So beautiful are the photo’s and warm and tender thoughts on love and family from you and others that shared.. I’m sorry to say it makes me a little angry at Dr. Emanuel. I hope you are right and he wakes up to the pleasures of life. I wake up everyday thanking God for another beautiful day and for the strength to “rage” for another day. You are inspiring.

July 30, 2022 @ 8:04 am

Thanks, Cynthia. I’ve been reading Dr. Emanuel’s many articles and his memoir since I wrote this, and this article about turning 75 is inconsistent with his generally positive attitude and overall love of life. I think he’ll change his mind over the next ten years. In the meantime, I hope you and I and all my friends 75 and older will continue to live “meaningful” lives, raging against the dying of the light. Thanks for following my blog and for your insightful comment!

July 29, 2022 @ 7:27 pm

Ken,

I have to say I agree with your style not the Doctors. Lucille Norberg would have been 99 this Sept and we just lost her a week a go. She was so vibrant and active till Covid. I think she would have hit over 100 if it weren’t for her having to be locked up in the house and not being about to get out like she loved to do.. So keep on going, don’t let the Doc scare you, just listen to Cindy…

July 30, 2022 @ 7:52 am

I didn’t know Lucille Norberg, although I certainly heard a lot about her. Sounds like she lived life to the fullest until the end. As far as listening to Cindy goes, I don’t have a choice about that. First, she’s always right. Second, even when she’s wrong she’s right. So I do what I’m told. She saved my life making me go to the doctor that time, though, so I ain’t complaining.

July 29, 2022 @ 2:56 pm

Ken: My #75 is in September, so I appreciate your comments and couldn’t agree more with your final conclusion. I am still going strong as a hospice chaplain and priest, and have the same plethora of children and grandchildren that are a part of my life (I actually have a 2 month old grandson, if you can believe it .….). My mother was 92 when she passed (3 years ago this weekend), and my father will be 100 in October. He still drives, plays a little golf and rides around the golf course as a marshal, and ushers at UVa football and basketball games (assigned to the Presidents box — such is the privilege of age). So, like you, I am looking forward to more good days than bad, and a lot of them. Thanks for the reminder that all is not always as others would make it to be. Blessings to you and your family.

July 29, 2022 @ 4:57 pm

Thanks, Dan. Sounds like you have good genes. As I read Dr. Emanuel’s article and a number of interpretive pieces about it, I was surprised to learn that so many people seem to think a meaningful, relatively productive life after 75 is not feasible. You’re obviously still making great contributions to those around you and to your growing family. Actually, I don’t know anyone our age who isn’t leading a meaningful life in one way or another. Maybe some people define meaningful too narrowly. Anyway, keep on going. I hope we both can make it to 100 with as much vigor as your father. He’s setting a great example for all of us!

July 29, 2022 @ 1:26 pm

Wow Kenny! I’m glad you are OK! You have an amazing memory, even when you are drugged! Your family members must be a delight and I feel sure that they will help you live long and have fun for many years.

July 29, 2022 @ 2:45 pm

Thanks, Glenna, I’m blessed with a good memory and a great family. I’m planning on a lot more fun, as I know you are. I figure you and I will make the next three or four ten-year class reunions.

July 29, 2022 @ 1:20 pm

Great thoughts Ken! “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” are great words to live by! Thanks and let’s keep on raging!

July 29, 2022 @ 2:43 pm

Thanks, Al. Let’s keep raging away for at least another quarter century and then some!

July 29, 2022 @ 12:38 pm

Hey Ken. Well written. I agree 100% with you. TURNED 75 IN May Never felt better or been happier, enjoying all the fun things life has to offer, watching my grandchildren grow up and excel in their lives. LUCKILY (knock on wood) have no ailments nor take any medication . Enjoy every day God gives us, know u are as I am

July 29, 2022 @ 2:41 pm

Thanks, Patricia. I didn’t realize until I sat down to write this how much living had been packed into the last five years. For me, that short summary made a joke out of the doctor’s statement that people 75 aren’t living a meaningful life. It’s a meaningful life to me and then some, and the same is true for you and so many more of my 75 and older friends. My guess is he’ll change his mind when he turns 75, or before. Every day is a blessing.

July 29, 2022 @ 12:12 pm

What a great article, and being older than you I sincero appreciated your story.

July 29, 2022 @ 2:35 pm

Thanks, Gary. Trouble is you don’t look older than me!

July 29, 2022 @ 11:41 am

As usual, great article (from your 75-year-old college roommate). 🙂

July 29, 2022 @ 12:23 pm

Hey Mike! Hard to believe we’re at the three quarter century mark. Or that it’s been a half century since we lived at 33 University Circle. Those were great times. I read an article about Anna Anderson and Manahan yesterday written by people who still believe she was Anastasia despite the contrary DNA evidence. I guess it’s fair to say those days were strange times, too. 🙂

July 29, 2022 @ 10:41 am

Happy Birthday and Congratulations on making it this far. I’m just a wee bit ahead of you, going on 77. However being a female gives more time. If you take into consideration my family genes, I’m here for another 20 years. Mother just past at 3 months short of 100 cursing and swearing because the family insisted that she go into a senior assisted home where she wouldn’t have to shovel snow any more (Canadian west). Some say 3 years of easy living did her in. Could be as she was still spry and kept the caretakers on their toes as she continually tried to make a break for it to go for a walk during COVID lockdown ( more fowl language was used). Grandma went at 98 and grandfathers at 85 and my father at 84 ( cancer got him because of heavy smoking). Doctors told me he had lung cancer from habitual misuse of nicotine ( what is the correct use of nicotine is my question).

Anyway I must say you always make my day with you humoureous emails.

Thank you and enjoy your wife and family.

July 29, 2022 @ 12:16 pm

Thanks, Jeannete, for your kind words. Those are great stories about you mother. Sounds like she believed in the maxim, use it or lose it. Keeping moving is one of the keys to aging well, I think, along with the strong genes, which your family exemplifies. My father, mother, and most of my ancestors made it into their 90’s and enjoyed their long lives. Let’s hope you and I can keep the trend going!

July 29, 2022 @ 10:38 am

Turned 75 yesterday. Four years ago myApple Watch told me to see my cardiologist. He’s sent me to the Heart Doctor who performed a quadruple bypass. Family history and bacon cheeseburgers. Can’t avoid the first but can the sec. Good to be here, with wife, family, my Trek and our favorite cruise line, Oceania.

July 29, 2022 @ 12:10 pm

Wow, Chad, I had no idea you had a bypass. I’m glad your watch gave you that warning and that you’re still here. Welcome to the three-quarter century club. Let’s hope we’re both still kicking at the century mark, too.

July 29, 2022 @ 10:29 am

And we are all glad for those past five years … though we did miss you at The 60th. You and Cindy will just have to hang on for another four years.….

FYI — Dr. Emanuel (ironic name…) is an advocate for euthanasia … and not always with the permission of the person.

July 29, 2022 @ 12:07 pm

Thanks, Don. I plan to make it to the 65th, 70th, 75th, etc. Dr. Emanuel is an interesting guy. His brother Rahm is more famous, and his other brother Ari is a Hollywood super-agent. I’m reading the doctor’s book, Brothers Emanuel. Fascinating family. My guess is the doctor will change his mind before he turns 75.

July 29, 2022 @ 10:22 am

And as living for a meaningful life at your age, you certainly are. You have had such a positive influence on so many people — and animals!

July 29, 2022 @ 12:04 pm

Thanks again, Lucian. Yeah, there are two dogs and four horses who want to be fed everyday!

July 29, 2022 @ 10:13 am

Truly beautiful, Ken. Couldn’t agree more.

July 29, 2022 @ 12:02 pm

Thanks, Bob.

July 29, 2022 @ 10:09 am

You’re the youngest 75 I’ve ever seen!

Keep it up

July 29, 2022 @ 12:01 pm

Thanks, Lucian. I plan to hang around a while.

July 29, 2022 @ 7:36 pm

We all have so much to be thankful for.…if we only take the time to think about these things..things don’t always turn out the way we hoped or plan but when we stop a moment we remember the good times and things we have…love your writing…you always make us think…

July 30, 2022 @ 7:56 am

Thanks, Sandra, for the kind words. You are so right about being thankful. There are some bad times mixed in with the good these days, but every day is still a blessing. Writing this piece helped me remember that. For me, so many blessings have been packed into the five years after that surgery.