The False Confession

In 1985, my former home state of Virginia came within eight days of executing an innocent man. Virginia has the longest relationship with the death penalty of any state, having executed more than 1,300 people, starting with Captain George Kendall by firing squad in Jamestown in 1608 for espionage, and the pace has continued in modern times. Since the Supreme Court affirmed the death penalty in 1977, Virginia has executed 113 inmates.

For 300 years, Virginia hanged capital defendants. In 1909 the state abandoned the gallows in favor of the electric chair. “Old Sparky” is still available in Virginia at the option of a condemned inmate, but most now choose to die by lethal injection.

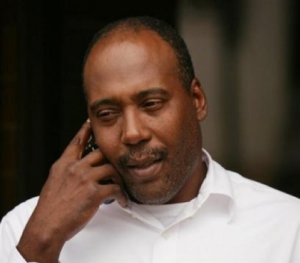

Earl Washington, Jr., was 23 in September, 1985, when the Culpeper Circuit Court sentenced him to death. He had lived all his life in Fauquier County. The local schools pegged him as a slow learner and placed him in special education classes. He dropped out of high school and worked as a day laborer, mostly on local farms.

On the night of May 21, 1983, Earl and his brother were drinking at his aunt’s house in Bealeton. They argued and Earl got mad. He had seen a pistol in the house across Route 17 when he used the telephone there.

At 3 a.m. that night the sound of breaking glass awakened Hazel Weeks, a 78 year old widow. She got out of bed and found a young black man in her hallway. He hit her over the head with a chair and struck her twice more while she was on the floor. She offered to pay him to spare her life. “Where is your money?” he said. Blood soaking her gown, she staggered to her bedroom and gave him her purse. He took it and fled. She later discovered that he had also stolen a pistol from her kitchen.

When Deputy Denny Zeets responded to Hazel’s call, he heard gunshots across Route 17. At Earl’s aunt’s house, he found Hazel’s purse and Earl’s brother with a gunshot wound to his foot. He said Earl shot him accidently and ran away. At dawn, the police arrested Earl in a field near Hazel’s house.

A series of interrogations followed. Earl confessed to the assault on Hazel early on. The investigators then questioned him about a string of violent crimes near Warrenton. He confessed to ten felonies, including several sexual assaults.

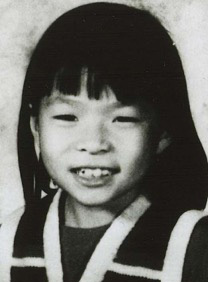

A year earlier, Rebecca Williams, a 19 year old mother of three, crawled out on the porch of her apartment in nearby Culpeper, naked and bleeding from 38 stab wounds. She survived only long enough to tell her neighbors that a lone black man attacked and raped her. Her murder remained unsolved when Earl attacked Hazel. Under persistent questioning, Earl confessed, providing details the investigators believed only Rebecca’s murderer could have known.

In the lead-up to Earl’s trial, he recanted all the confessions except the attack on Hazel, and facts emerged that cleared him of most of the crimes. By January, 1984, the prosecution dropped all charges except those involving Hazel and Rebecca, and Earl’s trial went forward.

The key issue was the veracity of Earl’s confession to Rebecca’s murder/rape. The investigators did not record the interrogations, but Agent Reese Wilmore had written a lengthy transcript of a final session about Rebecca, and Earl had signed it. Wilmore read the transcript to the jury.

The defense argued that Earl confessed to crimes he didn’t commit because he is mentally impaired. Experts testified that his IQ scores ranked in the bottom two percent of adults and estimated his mental age as 10 years old.

The jury found Earl’s confession convincing beyond a reasonable doubt. They recommended the death sentence and the judge followed their recommendation.

Earl arrived on death row in Mecklenburg on May 4, 1984. Unlike California, where appeals last longer than the defendant’s life, Virginia’s appellate process is streamlined. Earl’s appeals to the Virginia and U.S. Supreme Courts failed quickly, and the state scheduled his execution for September 5, 1985. Federal habeas appeals were still available, but Earl’s attorney abandoned the case, leaving him unrepresented as his final days ticked by.

A fellow death row inmate, Joe Giarratano, thought Earl was innocent. A high school dropout with no legal training, Giarratano drafted and filed a brief arguing that executing a capital defendant, who had no lawyer, was unconstitutional.

The jailhouse-lawyer filing caught the eye of a Manhattan law firm, Paul, Weiss. The firm sent a young associate to Mecklenburg to meet with Giarratano. The first words out of Joe’s mouth were: “Earl Washington has an IQ of 69, an execution date three weeks away, and no lawyer. What the hell are you going to do about it?”

Attorneys at Paul, Weiss responded by working around the clock for the next ten days. On August 27, the firm filed a petition for a stay of execution. It was granted just eight days before Earl’s execution date.

The stay gave the firm breathing room to launch a robust appellate defense, and for the next decade it managed to hold the state at bay.

Forensic science advanced. In 1993, a DNA analysis cast doubt on Earl’s guilt, but a rule in Virginia barred appellate courts from considering evidence raised more than 21 days after a jury verdict. Earl’s appeals failed.

By late 1993, only a Governor’s pardon stood between Earl and Old Sparky. Governor Douglas Wilder was Virginia’s first and only black governor. His critics claim he feared that pardoning a black man accused of murder might jeopardize his presidential aspirations. Wilder vehemently denied this. For whatever reason, he delayed his decision until his last day in office and then split the baby. He denied the pardon, but commuted Earl’s death sentence to life in prison.

By 2000, DNA analysis had advanced in sophistication, and a new battery of tests exonerated Earl. Governor James Gilmore granted him a pardon, and he walked out of prison in 2001.

In 2002, DNA samples in Rebecca’s case matched the DNA of Kenneth Tinsley, a man convicted of rape in Albemarle County. He pled guilty to Rebecca’s murder/rape in 2007.

Why did Earl confess to a murder he didn’t commit and how did he provide details about it that only the murderer should have known? The easy answer would be that his interrogators coerced the confession, but there’s another possibility. In a fascinating book about Earl’s case, An Expendable Man, by Margaret Edds, she discusses the theory that Earl spent his life on pins and needles, not understanding what people wanted from him, but trying to guess. He was anxious to please, susceptible to suggestions, and sensitive to cues, hints, and body language. A close look at the interrogations indicates that he gave his questioners the answers he thought they wanted and that they unintentionally tipped him off to the details of the crimes. For example, he originally said Rebecca was black, but after reading the reactions of his questioners, he quickly changed his answer to white.

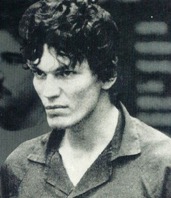

In last month’s post, I stated my view that Richard Ramirez, The Night Stalker, deserved to be put to death, but Earl’s case stands as a convincing counterargument against the death penalty. Only a combination of serendipitous circumstances saved him: Giarratano’s improbable intervention, Paul, Weiss’s last minute heroics, and Governor Wilder’s precarious commutation.

Unfortunately, Earl’s cautionary tale is not unique. The advancement of forensic science has exposed scores of wrongful convictions. Since 1973, 155 death row inmates have been exonerated.

The death penalty is unforgiving. One mistake is too many, and we’ve almost made 155 that we know about. One way to reconcile the conflicting emotions inspired by the Night Stalker’s savagery and Earl’s story would be to restrict the death penalty to the most heinous crimes where there is absolutely no doubt of guilt. If we can’t do that, we should abolish it altogether, because the risk of executing an innocent defendant under current laws is too great.

Post Script: In 2007, Virginia paid Earl $1.9 million to settle his claim of wrongful conviction. At that time, he was a maintenance worker, married, and living in Virginia Beach.

In 2002, the Supreme Court ruled in Atkins v. Virginia that the execution of a mentally impaired defendant is unconstitutional.

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

The press dubbed him the Night Stalker, and a modus operandi emerged. He broke into houses late at night, shot the men, and raped and murdered the women, leaving behind Satanic symbols painted in blood or carved in flesh. His attacks were violent orgies, stabbing, slashing, hacking with a machete, and bludgeoning with a hammer. His victims ranged in age from 6 to 83 years old, all races, all walks of life.

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.

A feverish competition for his affections broke out among hybristophiliacs, women who are sexually aroused and attracted to men who have committed violent crimes. Scores of women wrote him love letters and visited him on death row. Even one of the jurors at his trial, Cindy Haden, fell in love with him. She sent him a Valentine’s Day cupcake with an inscription in icing, “I love you,” and brought her parents along on one of her visits to meet him.

My wife and I rented three upstairs rooms in a big old house in White Hall, Virginia, right after we married. The house was the original “White Hall,” we were told, where travelers boarded in the old days on their way from Charlottesville across the mountains. We loved that place. It sat on a ridge overlooking a picturesque field where Angus cattle grazed.

My wife and I rented three upstairs rooms in a big old house in White Hall, Virginia, right after we married. The house was the original “White Hall,” we were told, where travelers boarded in the old days on their way from Charlottesville across the mountains. We loved that place. It sat on a ridge overlooking a picturesque field where Angus cattle grazed. home soon.”

home soon.” Couple months later, we came home on a cold rainy night to find Mousy on our welcome mat, desperately trying to keep two newborn kittens warm. We gathered them up, rushed inside, and held them over the radiator. One had already frozen to death. The other, Geraldine, survived.

Couple months later, we came home on a cold rainy night to find Mousy on our welcome mat, desperately trying to keep two newborn kittens warm. We gathered them up, rushed inside, and held them over the radiator. One had already frozen to death. The other, Geraldine, survived. Mousy and her offspring left us one by one in the late 80’s. Lazy Bones, the last of her line, laid down beside our pool one breezy summer day in 1990, stretched out, yawned, and went to sleep for good, bringing to a close Mousy’s long happy chapter in our lives.

Mousy and her offspring left us one by one in the late 80’s. Lazy Bones, the last of her line, laid down beside our pool one breezy summer day in 1990, stretched out, yawned, and went to sleep for good, bringing to a close Mousy’s long happy chapter in our lives.