Turning Points

My seventy-fourth birthday rolled by this month. I’ve been looking back since then and thinking about turning points. There are so many and they go way back.

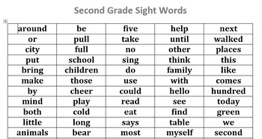

I almost failed the second grade. I was in love with Mrs. Halper, but her weekly spelling tests broke my heart. She called out eight words. We scrawled the letters in cursive. She collected the papers, circled in red the ones we got wrong, and handed them back to us. My paper was always the bottom score in the class. Almost all my words were circled, test after test.

Half-way through the school year, Mrs. Halper told Mom she couldn’t pass me to the third grade unless I learned to spell. They settled on a plan. Mrs. Halper drew up a big list of words each week. She worked with me on it after school, then Mom sat with me at the kitchen table each night. She called out the words. I wrote them down. She corrected them, and we did them again. And again.

I can’t pinpoint the moment or explain how it happened, but somewhere along the line, I began to develop a feel for the art of orthography and its maddening inconsistencies. I got four right on a test in February. Five the next week. Six a month later. Mom cheered when I brought that one home.

The big moment came the week before Easter. Mrs. Halper called out the eight words. I wrote them down. During nap time, I peeked through my fingers at Mrs. Halper as she graded our tests. A few minutes into it, she laid down her red pen, dabbed at her pretty blue eyes with a tissue, then smiled at me through tears. Later that day, she thumbtacked my paper to the bulletin board, and when we went out to recess, she kissed me on the cheek. I almost fainted.

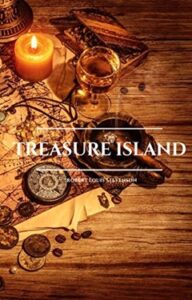

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

“I remember him as if it were yesterday, as he came plodding to the inn door, his sea-chest following behind him in a hand-barrow — a tall, strong, heavy, nut-brown man, his tarry pigtail falling over the shoulder of his soiled blue coat, his hands ragged and scarred, with black, broken nails, and the sabre cut across one cheek, a dirty, livid white. I remember him looking round the cover and whistling to himself as he did so, and then breaking out in that old sea-song that he sang so often afterwards: Fifteen men on the dead man’s chest —/Yo-ho-ho, and a bottle of rum!”

I could see Billy Bones and hear him singing as clearly as if he’d walked into my bedroom. Mesmerized, I read on for hours. Jim, Long John, and the pirates took me across the seas in search of buried treasure, and I never returned. Treasure Island became the first leg of a life-long journey borne on the wings of artfully told stories, wending my way through a thousand worlds to a B.A. in English Literature, through careers in teaching, law, and business, to come to rest in my seventh decade in Whippoorwill Hollow.

One of the worlds I visited along the way was Denmark’s Elsinore Castle in the Middle Ages. When I was seventeen, I walked on unsteady legs to the front of the room and stood before my classmates, high school seniors, sitting in rows of desks, all looking at me, waiting.

Each of us had to recite from memory the soliloquy from Act I, scene ii of Hamlet, 31 lines, 259 words. Presenting it without faltering would be enough to secure a good grade, but I wanted to do more than that. Hamlet was a sad, conflicted prince, plagued with self-doubt and self-loathing. Struggling with world-class adolescent insecurities, I felt Hamlet’s anguish and thought I could give his troubled heart a voice if I could find the courage to bare my soul in front of my friends, but courage wasn’t my strong suit. Up to that point, I’d never taken center stage or done anything to set myself apart. I preferred to hide in the shadows where it was safe, but that day, inspired by Shakespeare and a gifted teacher, Mr. Turner, I desperately wanted to step forward into the light.

Feeling vulnerable in front of my classmates, I fixed my gaze on reddish-gold spears of autumn sunlight coming through the back windows, then took a deep breath, and held my trembling hands up before me. “Oh that this too, too solid flesh would melt,/Thaw, and resolve itself into a dew.” My voice broke, then steadied as Hamlet’s sorrow swelled up inside me and took control. “How weary, stale, flat, and unprofitable/Seem to me all the uses of this world,” I said, meaning it.

The next 26 lines took me deep down inside myself to a place I’d never been, where my inhibitions, doubts, and fears fell away. For one minute and fifty-five seconds, I melted into poetry that seemed to have been written for me centuries before I was born. “But break my heart,” I said at the end, fighting back tears, “for I must hold my tongue.”

Dazed, I walked to my desk and sat down. Emerging slowly from the mystical spell of Shakespeare’s lyrical iambic pentameter, I realized everyone had turned toward me, some with big smiles, others with tears in their eyes. They were clapping, and the applause went on and on.

Over the following weeks, I presented other scenes from Hamlet to good effect. For a dazzling few months I had visions of becoming the next Richard Burton, but I soon proved to be a one-trick pony, a reasonably good Hamlet, but mediocre to painfully awful in every other role, and my thespian aspirations met a swift, merciful death.

That performance stayed with me in a more important way, though. It became a small cornerstone of confidence, the first stone set in the construction of a long life.

I’d like to pretend here that I’m self-made, that hard work, sacrifice, and talent brought me to the good place where I find myself today, but looking back with a clear eye, I see a thousand turning points where flat-out pure luck played the decisive role and a thousand more where I couldn’t have gone forward without the help of someone who extended a hand to me gratuitously and unbidden.

A few years ago, a guy I hadn’t seen in fifty years tracked me down to thank me for talking him out of quitting our college fraternity when he was a pledge. He said I saved him from making a life-altering mistake. I appreciated his thanks, but wondered why he went to so much trouble. It was such a small thing that happened so long ago.

He died the following year, and I learned he’d been fighting cancer for a long time. I understood then. I was one of many on a long list.

Mrs. Halper, Mom, my aunt and uncle, Mr. Turner, and so many of those who helped me are gone now. I thanked some of them before they left. I wish I had a second chance with the others.

Many are still here. My list is long, too, but I’m fortunate. I have time.

Post Script: Suzie Glass and I were the last two kids standing in the seventh-grade spelling bee when the proctor called out the word “medieval.” It sat me down and Suzie won. To this day, that word aggravates me. Say it out loud, then explain to me why in hell it’s spelled like that.

Standing on the tarmac, I looked up at the face of the jet. A basketball-sized gash dented the nosecone. Blood, entrails, and feathers covered the co-pilot’s windshield. Winnipeg is the capital of Manitoba, the Canadian province known as the land of a hundred thousand lakes. Thousands of geese flock to the lakes in the summer and pose a flight risk to aircraft on approach to the airport. The pilot said we were lucky. On one of her flights, a goose blew out the windshield and splattered innards all over the cockpit.

Standing on the tarmac, I looked up at the face of the jet. A basketball-sized gash dented the nosecone. Blood, entrails, and feathers covered the co-pilot’s windshield. Winnipeg is the capital of Manitoba, the Canadian province known as the land of a hundred thousand lakes. Thousands of geese flock to the lakes in the summer and pose a flight risk to aircraft on approach to the airport. The pilot said we were lucky. On one of her flights, a goose blew out the windshield and splattered innards all over the cockpit.

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles.

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles. I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps.

I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps. His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not.

His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not. Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.