Keeping the Promise

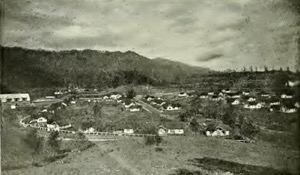

In these troubled times, memory reels of my mother’s father keep rolling through my mind. He lived through the 1918 influenza pandemic in Keokee, Virginia, a coal-mining town where kids call their grandfather Papaw.

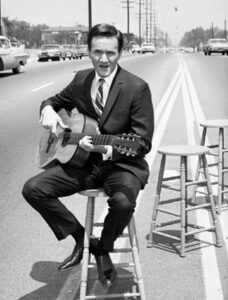

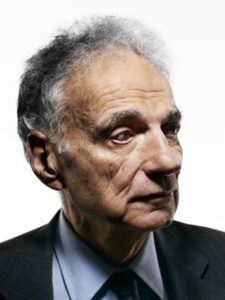

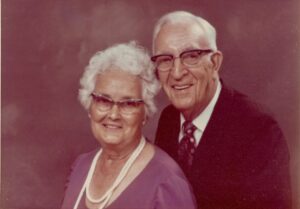

When I was little, Papaw and Nanny lived near our house on route 60 just west of Yorktown. One of my earliest memories is dancing with him in their living room to songs like Buttons and Bows and Swinging on a Star played on a crank-up Victrola. He picked me up and waltzed me around the room with soft laughter that came from deep in his chest.

When I turned surly and lazy in my teen years, he tried to lift me out of my funk with heartfelt talks, but I wouldn’t listen to him. I wouldn’t listen to anyone.

After we moved away to White Hall and I outgrew my sour attitude, Papaw and Nanny came to visit us. I worked on the Maupin farm that summer. On a hot as hell day we baled hay in a field beside the parsonage. When I came home at quitting time, Papaw met me at the door. “I saw you out there, boy,” he said, smiling. “For a long time I thought you wouldn’t amount to anything, but it looks like I was wrong.” That moment meant a lot to me then. It still does.

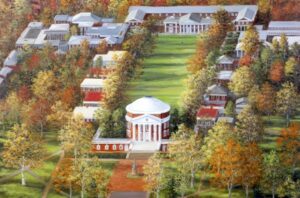

When he retired from his job as a carpenter for the Navy’s Cheatham Annex, he and Nanny moved to St. Cloud, Florida. On UVA’s spring break, I rolled down to Daytona Beach for the annual college student wild times. Midweek, I took a break from the craziness and drove over to St. Cloud.

That night after supper Papaw sat in a rocking chair on the porch, smoking his pipe, and we talked easily for a while. Then he fell silent. I felt something heavy coming, so I kept quiet.

He cleared his throat. “Your momma told me how good you’re doing in school,” he said. “She says it’s because you’re smart, but I suspect it’s got more to do with hard work.” He paused. Crickets sang in the bermuda grass. A car coasted down the street. He looked over at me. “You try real hard now, but that hasn’t always been your nature.”

I looked away, uncomfortable about the times I’d disappointed him.

“I want you to promise me you won’t slide back,” he said. “Promise me you’ll always try hard.”

I kept my head down, not sure I would keep such a promise. He waited me out. “I’ll try,” I finally said in a small voice.

He stared at me for a few moments, then resumed smoking and rocking. “I’m proud of you, boy,” he said gently.

I didn’t know it then, but sometime before we had that talk the doctors found cancer in his knee. They wanted to amputate his leg. He wouldn’t agree to it. Over the next two years the cancer metastasized.

He had only a few months left when my brother and I drove down to St. Cloud. Papaw didn’t know we were coming. He was sitting in the living room talking to my uncle when we walked in. He grabbed my arm, pulled me down to him, and pressed his cheek against mine. “I thought I’d never see you again,” he choked out. It was the only time I ever saw him cry.

He took his last breath in bed at home with Mom by his side. Nanny had lost her will to live and had been hospitalized shortly before his death. She died a month later.

Researching my mother’s family tree decades after they passed away, I came across documentation of a marriage in Keokee in 1917 between a man with Papaw’s name and Una Mae Collier. Nanny’s name was Martha Alice Huff, so I thought there had to be some mistake, but the records called out Papaw’s correct birth date and occupation as a coal miner. I dug deeper and found a birth registry that said this couple had a son, Ralph, in 1918. The details about the father fit Papaw.

These records surprised me, but it was the death certificates that took my breath away. The infant son died early in 1918. Una Mae perished in October of that year during the second wave of the influenza pandemic. She was 18 years old. Papaw lost a sister two weeks later. The following year his mother fell prey to the third wave of the virus.

Papaw’s father survived the pandemic and struggled on for a decade, but he couldn’t live with the grief. The coroner’s report listed his cause of death as a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head.

Another death certificate revealed one last heart-breaking blow. After Papaw found Nanny and somehow summoned the strength to rebuild his life, their third child, Jack, died of spinal meningitis.

None of this made sense to me. I couldn’t reconcile these devastating tragedies with Papaw’s steady optimism. The man I had known and loved was content, serene, happy.

Mom was in her eighties when I asked her about the records I had found. “Is any of this true?”

“It’s all true. Daddy never spoke of it, but people in Keokee told me about those days. They said Una Mae was his childhood sweetheart. She and Daddy had only been married a little over a year when she and the baby died.” She shook her head sadly. “Daddy was real close to his momma, too.”

I asked about Papaw’s father. “I was a little girl when he killed himself. I remember Daddy crying about it and saying over and over again, ‘He finally went and did it.’”

“How did Papaw live with so much loss?”

“I don’t know, but he kept going somehow.” She gazed past me into the distance. “Daddy was real strong.”

I waited a respectful time and then said, “Tell me about Jack.”

Mom said her brother came down with a raging fever. The doctor told them there was little hope of survival and quarantined the family in the house. Papaw never left Jack’s bedside, wiping him down with ice and squeezing cold water from a cloth into his mouth, but the fever wouldn’t break. He died at dawn, a few days after his eleventh birthday.

“You remind me of Jack sometimes,” Mom said in an off-handed way. “You resemble him some, and he was good in school, like you.”

“You remind me of Jack sometimes,” Mom said in an off-handed way. “You resemble him some, and he was good in school, like you.”

That casual comment sank in slowly.

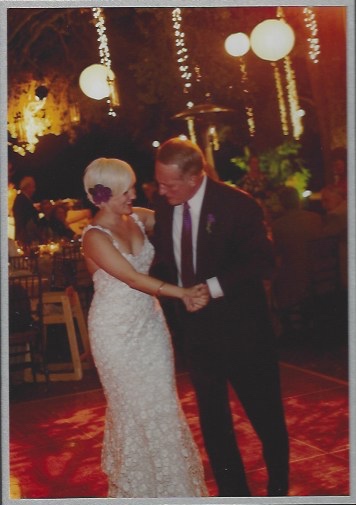

When our first grandchild was born, her parents asked me what I wanted her to call me. We live in California, about as far away geographically and culturally from Appalachia as you can get. Sometimes people look at me funny when one of my grandkids calls me Papaw, but it always gives me a warm feeling inside.

During this pandemic, I’m sometimes fearful about the future and anxious for my family. I can only speak to my children and grandkids from a distance or technologically, and the CDC says hugging them might kill me. My closest social contacts are Drs. Fauci and Birx. The high point of the day is walking the dogs while decked out in hazmat mask and gloves. Ruthlessly sheltering in place, I’m simultaneously scared and bored.

That’s how I feel in my weak moments, but most of the time I’m okay. I have an advantage. When my spirit falters, I call to mind the promise I made, and I try hard to meet the standard set a century ago by the Papaw who came before me. Despite all his suffering, he was a good old guy with an easy smile, unfailingly kind and patient. I never saw him angry; I never heard him raise his voice; and I only saw him cry once. When he was alive, I took his good humor for granted. Today, I’m inspired by it.