Moonshine

Carl drove a flatbed truck through the woods to the dump on a Saturday afternoon. I rode shotgun. He was the trash collector for Acme Visible Records. I was his assistant, working a summer job before returning to UVA.

We had already clocked four hours of overtime that morning when Carl said we had to make the trip to the dump. Strangely, he insisted that we punch our time cards before we climbed in the truck.

“Why clock out?” I said. “We’re still working.”

In his sixties, black hair swirled with gray, smile lines crinkling around his crystal blue eyes, he patted me on the shoulder. “Just do like I say,” he said. I followed Carl’s direction, but I wasn’t happy about it.

At the dump, Carl backed the truck up to a pit and we wrestled barrels of trash to the rear of the flatbed to empty them out. When we got back inside the cab, he reached under the seat and lifted a mason jar into his lap.

“You ever had shine?” he asked me.

Looking at the jar warily, I understood then why we were off the clock. “No,” I said.

“Figured as much, you bein a preacher’s boy.” He unscrewed the lid, took a sip, wiped his mouth on his sleeve, and handed me the jar. “Mule Kick,” he said.

Clear as water, it gave off a faint sweet scent. I hesitated, worried it wasn’t safe to drink.

“Go ahead,” Carl said. “I made it. It’s good shine.”

“Go ahead,” Carl said. “I made it. It’s good shine.”

I trusted Carl. I lifted the jar to my lips.

“Go easy,” he said. “It’s powerful strong.”

I swallowed a teaspoonful. It scorched my throat like hot candle wax and splashed fire in my belly. At the center of my chin I felt a stinging sensation. It divided in two, rolled up the sides of both jaws, and exploded above my ears like twin mallet blows to my temples. I saw stars. When I could breathe again, I blew out hard.

Carl chuckled. “That’s why I call it Mule Kick, boy.”

We each took another sip. It went down easier the second time, but not by much.

“The trick with shine,” Carl said, “is to know when to stop. Best set her down now.” He screwed the lid on the jar and slid it under the seat.

“You be careful next time you drink shine,” Carl said, as he drove us back to the plant. “A bad batch can kill you. Watch the man who made it. Make sure he sips it before you have a taste. He don’t drink it, you don’t drink it.”

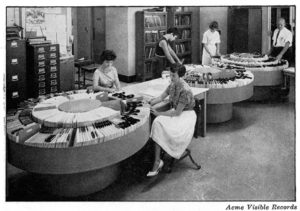

How to drink moonshine wasn’t all I learned that summer. Located on 60 acres along Three Notch’d Road in Crozet, Virginia, Acme Visible Records’ 600 workers made file cabinets and printed business records. The Maintenance Department Manager was the best boss I ever had. A straightforward plain-talker, he told me what he wanted me to do and how he wanted me to do it. When I screwed up, he was firm, but fair. I always knew where I stood. The executives I worked with over the years that followed could have learned a lot from him.

He rotated me through the department as a pinch hitter for employees on vacation. My last assignment was assisting the trash man, Carl. In the main room of the plant the presses clacked away, printing customized business records. The press operators discarded a lot of paper from bad runs. Carl and I had to clear it out of the way so the presses could keep rolling. We tossed it into wheeled bins, rolled it back to a machine that scrunched it into bales, then hauled the bales out to the dock for recycling.

“Slow it down, boy,” Carl said to me fifty times a day. “You’re workin us out of a job, runnin around here like a racehorse.” Carl tarried at every press, socializing with the operators, joshing with the men, flirting with the women. “Good people work here,” he told me. “Friends and neighbors. We got time to say a few kind words. The trash ain’t goin nowhere.”

I wasn’t good at slow. I thought we were wasting time, and I wondered why management didn’t force Carl to move along. Years later, I came to understand it. Carl’s job was one of the few that required interaction with everyone. His socializing was part of the glue holding the network of employees together. Working with large organizations over the years, I learned the value of glue, especially when times were tough and work pressures mounted. Management at Acme Visible knew Carl was good for morale. Besides, despite his meandering pace, he always got everything done by the end of his shift.

I wasn’t good at slow. I thought we were wasting time, and I wondered why management didn’t force Carl to move along. Years later, I came to understand it. Carl’s job was one of the few that required interaction with everyone. His socializing was part of the glue holding the network of employees together. Working with large organizations over the years, I learned the value of glue, especially when times were tough and work pressures mounted. Management at Acme Visible knew Carl was good for morale. Besides, despite his meandering pace, he always got everything done by the end of his shift.

Way before the Zen philosophy caught hold in the U.S., Carl was big on living in the moment. I was forever looking forward to the weekend, wishing it was Friday. Carl would shake his head and smile. “You’re wishin your life away, boy. Best to get the most out of what’s goin on right here, right now. Before you know it, you’ll be old like me, and you’ll wish you was back here on a Monday mornin, balin paper.” I didn’t believe him then. I do now.

Carl spent a lot of time schooling me on how to get girls. Most of what he said can’t be repeated in polite company, but one of his G‑rated lectures stuck with me. “Every girl’s got somethin special,” he said, “pretty eyes or silky hair, a nice smile or how smart she is. Look for that part and tell her how special it is. You’ll be surprised how good it makes her feel because you might be the only one who ever told her.”

I put those words in Billy Kirby’s mouth in my novel, Old Wounds to the Heart. By then, Carl’s maxim had proved to be true countless times, not just for girls, but for everyone. Everyone has something special, and all too often it goes unrecognized and unmentioned. It helps to hear about it once in a while, and because of Carl, sometimes I made someone feel better with a few words of well-deserved praise.

I put those words in Billy Kirby’s mouth in my novel, Old Wounds to the Heart. By then, Carl’s maxim had proved to be true countless times, not just for girls, but for everyone. Everyone has something special, and all too often it goes unrecognized and unmentioned. It helps to hear about it once in a while, and because of Carl, sometimes I made someone feel better with a few words of well-deserved praise.

Carl and I worked together fifty years ago. He’s passed on by now. Sadly, Acme Visible Records has passed on, too. The computer age rendered its hard-copy records obsolete.

After the company closed its doors, the EPA found soil and ground-water contaminants in a lagoon where the plant had routed its industrial wastewater. Site remediation began in 2011. The clean-up was still on-going last year.

I hope the contamination is resolved successfully and that it doesn’t completely overshadow the company’s history. It was a great place to work, and it provided a middle class standard of living to hundreds of people in the hollows and coves around Crozet and White Hall for a half century.

Summer jobs for students have all but died out now, too, I’m told. This is a shame. I learned more from summer jobs than I did at UVA, invaluable life lessons from people like Carl, one of the wisest men I ever met.

On my last day at Acme Visible, Carl and I walked out to the parking lot together. Standing beside his pickup truck, we shook hands. Those gentle blue eyes smiled. “Don’t ever forget where you come from, boy.” He squeezed my shoulder, climbed in his pickup, and drove away.

Our paths never crossed again, but Carl’s sage advice stayed with me. And I never forgot.

Post Script: I changed Carl’s name for this piece, but some of my Virginia friends may recognize him anyway. He was one of a kind.