The Old Horse

A horse lay on his side on the pavement at the intersection of Clear Valley Road and Long Valley Road. He wore the signs of old age, a scruffy brown coat, bloated girth on a skinny frame, protruding ribs and hip bones. A crowd of about 20 people had gathered around him. A man pulled on his reins while others pushed him and prodded him. “Come on, Papa! Up now! Get on up! Up you go!” The old horse lifted his head feebly, let it fall back to the concrete, and heaved a long slow breath.

A horse lay on his side on the pavement at the intersection of Clear Valley Road and Long Valley Road. He wore the signs of old age, a scruffy brown coat, bloated girth on a skinny frame, protruding ribs and hip bones. A crowd of about 20 people had gathered around him. A man pulled on his reins while others pushed him and prodded him. “Come on, Papa! Up now! Get on up! Up you go!” The old horse lifted his head feebly, let it fall back to the concrete, and heaved a long slow breath.

Wearing riding breeches and boots, a gaunt woman with close-cropped dark hair and tattooed arms stood over the horse, scowling. “There’s nothing wrong with him,” she said. “He’s stubborn. He just doesn’t want to get up.”

Wearing riding breeches and boots, a gaunt woman with close-cropped dark hair and tattooed arms stood over the horse, scowling. “There’s nothing wrong with him,” she said. “He’s stubborn. He just doesn’t want to get up.”

I parked my car across the street from the crowd and got out. Lonna, a horse owner and long-time member of the Hidden Hills Equestrian Committee, ran over to me with her cell phone in hand. “I’ve been trying to reach a vet, but no one’s available. Do you have someone you can call?”

My call to my vet went straight to voicemail. “Hey, Doc. This is Ken Oder. It’s an emergency. A horse is down on Clear Valley Road in Hidden Hills. Call me as soon as you can.”

Lonna tried another number and raised a vet’s assistant. Her boss was in the field, but she said she’d try to reach him. “The horse is 38 years old,” Lonna told her. “I’m afraid we may need a hauler, too.”

I walked over to the horse. His head lay listlessly on the pavement, his tongue lolling out of his mouth, a small pool of blood under his muzzle. His breaths came in irregular heaving gusts.

I knelt beside him. The blood came from a cut on his lower lip. It didn’t look serious. I didn’t see any other wounds. I ran my hands over his legs and ribs. I felt no breaks. No swelling.

Most troublesome was his position, lying flat on his side. Horses can’t stay down for long. They sleep standing up in the “stay” position, three legs locked with a back leg bent at the hock and fetlock, ready for instant flight if a predator approaches. They can lie down for short breaks to take pressure off their legs, but if a horse is recumbent on its side for too long, its weight restricts blood flow to vital organs and compresses the lungs.

Horses rarely make it into their late 30’s. A 38-year-old horse is roughly equivalent to a 100-year-old man. This old horse was living on borrowed time before he went down. If we couldn’t get him up soon, he would certainly die.

The gaunt woman in riding gear stood a few feet away talking with another woman.

“What’s his name?” the other woman asked.

“Casey.”

“What happened to him?”

“Hell if I know. I was leading him down Long Valley when he fell down for no reason.”

The horse was bridled. No halter. No lead line. A saddle lay beside him that the men who tried to get him up had taken off him to ease his breathing. The woman wasn’t leading him when he fell. She was riding him. About 5 feet 4 and bone-thin, she was a light load, but still heavy enough to break down this old gelding. It angered me. No one, not even a small child, should have climbed on this old horse’s frail back.

A truck pulled up behind me, and my vet got out. I was greatly relieved to see him. He’d worked miracles for my horses, and Casey needed a miracle.

“Thanks for coming so quickly,” I said.

“I came as soon as I got your message. I was afraid it was one of your horses.”

“Not mine, thank God, but I hope you can help him.”

The vet looked Casey over. “First thing we have to do is get him up.”

The vet looked Casey over. “First thing we have to do is get him up.”

“They tried. He couldn’t stand.”

“Probably because his head’s downhill on this little slope. He can’t get his back legs under his weight. We have to turn him around.”

No small feat. Horses weigh 1000 to 1200 pounds on average. I asked the strongest-looking guy in the crowd to help me, and together we managed to pull Casey slowly around by his tail until his back legs were downhill. When we let go of him, he rolled over on his belly into a sitting position like a Sphinx, his head up, his legs tucked under him. I twisted his tail and pushed him, but he wouldn’t stand.

“I’ll get him up,” the vet said. He unspooled a hose from a barrel of water in his truck bed and sprayed it over Casey’s head. “They hate this,” he said. “It always works.”

Sputtering and shaking his head, Casey got his rear hooves under him and pushed his hindquarters up in the air, but he was still down on his knees in front, like he was praying at the altar of the god of old horses. With a great effort, he lifted one front leg and got his hoof on the ground, then the other leg, heaved his front end up, and stood on all fours.

The crowd cheered.

“Let’s see how he walks,” the vet said. I led Casey across the road and back. His gait was slow, but regular.

While the vet went to his truck to get his bag, I stood beside Casey, stroking his head and neck. His big brown eyes were dull, and he didn’t look at me.

The vet checked him over, then gave him a shot of Banamine, a pain reliever that reduces inflammation. The vet told the woman wearing riding gear that Casey was exhausted but not seriously injured.

Thinking I’d offer to help her take him wherever he was stalled, I asked her where she was headed with him.

She snatched the reins out of my hands. “Well, I’m not taking him anywhere after the trick he pulled! He’s going straight back to the barn!”

She stormed away without a word of thanks to the men who tried to get him up, Lonna, me, or the vet.

“If she doesn’t pay you, I will,” I said to the vet.

“That woman’s the trainer,” he said. “I know the owner. She’ll pay.”

As the vet and I watched her lead Casey up Clear Valley, I wondered what kind of trainer would think it was a good idea to ride a 38-year-old horse. Casey plodded along behind her, breathing hard, his head down. They turned onto a trailhead and disappeared behind a hedgerow.

I thanked the vet again for coming so quickly and for saving Casey’s life. We shook hands, and he drove away.

The next day I rode Jackson on Hidden Hills’ trails, searching for Casey’s barn. I found him standing in a corral below High Ridge Road. He was up and eating hay. Over the next few weeks, I returned to his corral twice more. He seemed okay.

On a Monday morning in late March, I rode Marge up that same trail. When I came to the corral, it was empty, and the fence was down.

A young boy wrestled with a post-hole digger, setting new posts along the old fence-line. Knowing the answer, but hoping against it, I asked him what happened to the horse that was penned in the corral.

“The man say the lady’s old horse, he die,” the boy said.

I stared at him for a few moments, gripping Marge’s reins tightly, my jaw clenched.

“I am sorry, señor.”

“Gracias,” I said.

I rode Marge back to my barn. I gave my horses extra treats that day and lingered with them longer than usual.

I was reading Paulette Jiles’ novel, Stormy Weather, the day I learned Casey had passed. That night I came to the part where Ross Everett advises his girlfriend not to become emotionally invested in her horse, Smoky Joe. “Don’t get attached to a horse, Jeanine. We always outlive them. Except the last one.” I set the book aside and thought about that passage.

I was reading Paulette Jiles’ novel, Stormy Weather, the day I learned Casey had passed. That night I came to the part where Ross Everett advises his girlfriend not to become emotionally invested in her horse, Smoky Joe. “Don’t get attached to a horse, Jeanine. We always outlive them. Except the last one.” I set the book aside and thought about that passage.

I bought my first horse seven years ago. I have five now. I’m 77. Wilson is 25. Arthritis is eating away at his spine, and he has trouble controlling his back legs. Lily is only 15, but she has equine melanoma, arthritis in her hocks, and old injuries that never healed right. Wilson and Lily will probably go before I do. Jackson and Marge are 17. I hope to give them a close race to the finish line. Dolly is 10. She’s probably that last horse.

I haven’t followed Everett’s advice. I’ve given my horses my heart. It will break when they leave me and the wound will never heal, but I don’t regret forging my bond with them. When they’re gone, I’ll still have sweet memories of our partnership on thousands of great rides, the nickers that greet me when they see me coming, the nuzzles on my shoulder, the sense of peace, the communion, the love given and returned. The good times far outweigh the immense, overwhelming grief that will fall over me at the end.

I ignored Everett’s counsel with Casey, too. I barely knew him, but sometimes you can feel the spirit of a horse with the touch of your hand. When I stroked Casey’s head and face, I sensed he was a good old soul, who had tried hard to do what was asked of him. The day he fell, he was worn down, sad, and struggling to find the will to make a comeback. I’m glad he succeeded, if only for a few weeks.

His passing cost me some pain, but I don’t regret laying hands on him. He deserved affection and respect. He was a good horse to the end.

Rest in peace, old boy.

Opening Day, 1981 T‑ball season. Yankees v. Red Sox. Top of the first inning.

Opening Day, 1981 T‑ball season. Yankees v. Red Sox. Top of the first inning. “Fielder’s crouch,” Arnold said to Arlo. Arlo bent his knees and pounded his fist into his glove.

“Fielder’s crouch,” Arnold said to Arlo. Arlo bent his knees and pounded his fist into his glove. The third baseman, Robby, a drifty towheaded kid, stood on third base at parade rest, grinning vapidly at a pigeon flying over right field.

The third baseman, Robby, a drifty towheaded kid, stood on third base at parade rest, grinning vapidly at a pigeon flying over right field.

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

“Don’t give up on me.” He told me about surgery to remove tumors and scrape the lining of his lungs to stimulate his immune system. It sounded horrific. He did his best to appear hopeful, but I could tell he knew the score.

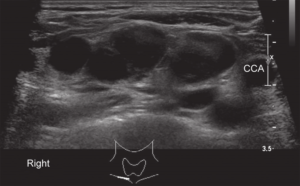

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

A few days later, he called with the biopsy’s results. The mole was benign; the dark tissue beneath it was cancerous. “I excised what I could see,” he said, “but this is an aggressive type of melanoma. You’ll need surgery to remove all the cancer cells.” He’d already called the City of Hope (COH), the top cancer treatment center in the region, and jammed me into the crowded calendar of its lead melanoma surgeon.

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

Stunned, I walked from the hospital to my truck. Memories of Paul, Papaw, Thom, Stephanie, and other friends, who lost battles with cancer, flooded my mind.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

Later, back at home, I reached out to my physical fitness trainer, a cancer survivor. She gave me understanding and encouragement and told me about an “affirmations” website. It seemed hokey to me at first, but over time, I found reassurance in its soothing mantras: I am strong; I will let go of negativity; I choose wellness and peace; I choose faith over fear.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

That night I dreamed I rode Lily on a moonlit trail. We entered a dark forest with branches arching over us. Deep into the tree tunnel, Lily stopped suddenly; her body tensed; and her ears pricked forward. Peering into the night-shadows ahead, I could barely make out the form of a big roan and a black-robed rider. Lily screamed, whipped around, and sprinted back the way we had come. Grabbing her mane to hold on, I heard the thundering hoofbeats of the roan behind us, gaining ground. I awoke just as we broke out of the trees into the moonlight.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.

So, it looks like Lily and I will outrun that big roan and the angel of death for a while longer. Each day, I’ll feed the horses at dawn, walk P.D., ride Lily and my horses over the trails of Hidden Hills, love Cindy, hug my children and grandchildren, keep my friends close, and give thanks from that new place deep down inside for that day and every day yet to come.