The Killer Storm

On August 20, 1969, Cindy and I awoke at 2 a.m. to a roaring, pounding din on the tin roof of our house in White Hall, Virginia. We jumped out of bed and ran to the window.

On August 20, 1969, Cindy and I awoke at 2 a.m. to a roaring, pounding din on the tin roof of our house in White Hall, Virginia. We jumped out of bed and ran to the window.

Lightning streaked across the sky. Thunder crashed. Through a silver sheet of water, we could barely see the big oak beside the house, its thick branches bowed downward, a lake swirling around the base of its trunk.

“Hardest rain I’ve ever seen,” Cindy said.

“Must be that hurricane they were talking about on the news,” I said.

“You think we’ll be okay?”

“We’ll be fine. It’s just a big storm. It’ll pass.”

I was right about the storm where we lived. Hurricane Camille blew through Albemarle County without causing much damage, but if we had lived in neighboring Nelson County, my confidence might have cost us our lives.

I was right about the storm where we lived. Hurricane Camille blew through Albemarle County without causing much damage, but if we had lived in neighboring Nelson County, my confidence might have cost us our lives.

At 2 a.m. when Cindy and I were staring out our bedroom window at the storm, John Fitzgerald rolled over in his sleep in Tyro, Virginia, just 30 miles south of us, and dropped his hand off the edge of his bed into cold water. Jarred awake, he bolted upright and peered into the darkness at the surreal scene of three feet of standing water in his bedroom.

His first thought was fear for the life of his infant son. When John and his wife, Frances, went to bed that night, they left their two-month-old baby in a bassinet in an adjoining room. John jumped up, sloshed into the other room, and switched on the light. In the midst of floating furniture, the bassinet bobbed gently like a little canoe on a rippling pond with the baby sleeping peacefully in its hull.

Frances splashed into the room. “Where’s the baby?” she screamed. John picked him up and handed him to her just as the electricity died and the light went out.

“Let’s get out of here,” Frances yelled.

John looked out the window. The Tye River, normally a hundred yards from their porch, had overflowed its banks and engulfed their home. Mud, rocks, and uprooted trees sped by the house on the back of raging floodwaters. “We can’t go out there,” he shouted.

Outside, the river would kill them. Inside the house, the water rose steadily. The attic was their only hope, John thought, but there was no access to it.

He waded back into the bedroom, retrieved a penknife from his pants pocket, climbed on top of a wardrobe, and cut a hole in the sheetrock ceiling. He helped Frances up into the attic, handed her the baby, and climbed up behind them. For the rest of the night, the Fitzgeralds rode out the flood astride the attic’s wooden rafters.

At dawn, the storm moved on and the river receded. John and Frances climbed down and went outside to find a landscape of death and destruction Camille had left in its wake. One corner of their house had been smashed away. A neighbor’s car had floated onto their porch and was wedged against the front door. The dead bodies of two women lay along the riverbank. A man’s cadaver was hung up in a fence below the house. A little girl’s hand reached skyward from a thick layer of mud caking the slope down to the Tye, the rest of her body buried beneath it.

At dawn, the storm moved on and the river receded. John and Frances climbed down and went outside to find a landscape of death and destruction Camille had left in its wake. One corner of their house had been smashed away. A neighbor’s car had floated onto their porch and was wedged against the front door. The dead bodies of two women lay along the riverbank. A man’s cadaver was hung up in a fence below the house. A little girl’s hand reached skyward from a thick layer of mud caking the slope down to the Tye, the rest of her body buried beneath it.

Like John, most of Camille’s Nelson County victims were caught unaware of its approach. Back then, there was no sophisticated storm-alert service to warn them about the storm’s magnitude or when it would arrive. It struck in the middle of the night while they slept, and with Nelson County’s steep mountainsides, narrow hollows, and deep ravines forming a perfect catch basin for the torrential rain, floodwaters swept many homes off their foundations before their residents could escape.

Camille’s deadliest aspect was the sheer volume of its rainfall, in some locations as much as 25 inches in 5 hours, which meteorologists computed to be the maximum amount of water the atmosphere could hold. Birds sitting in trees drowned. Creeks flash-flooded in mere minutes. Two thousand years of erosion took place in a single night, sweeping away miles of roads, 100 bridges, and 900 buildings. Property damage topped $100,000,000.

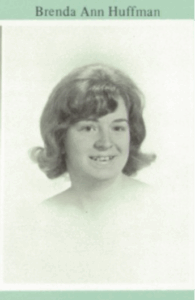

The toll in human lives was horrific. Camille killed 126 people in Nelson County; 184 statewide. Entire families perished. In Huffman Hollow, the flood wiped out whole branches of the Huffman family tree, killing 18 family members, ranging in age from 1 to 60.

I didn’t know anyone who died in the flood, but I had friends who lived through it, and they told me stories I’ll never forget.

One of my friends lived in a farmhouse perched on a hill overlooking a valley and a river. His family awoke that night to screams and ran out on their front porch. Through a gray torrent they saw the dim outline of houses floating on a churning lake that hadn’t been there when they went to bed.

One of my friends lived in a farmhouse perched on a hill overlooking a valley and a river. His family awoke that night to screams and ran out on their front porch. Through a gray torrent they saw the dim outline of houses floating on a churning lake that hadn’t been there when they went to bed.

People shouted from rooftops. “Help! Please help us!”

My friend ran down to the water’s edge. It was raining so hard he could barely see, and he had to cover his face to breathe. There was no way he could reach the people stranded on the water. He returned to the porch and stood there helplessly while his neighbors cried out to him.

There was an explosion. The lake whooshed away. A last burst of screams. Then silence.

There was an explosion. The lake whooshed away. A last burst of screams. Then silence.

Before the storm, a railroad overpass bridged the valley. The flood carried debris downstream that got hung up on the overpass’s struts, damming up the river and creating a huge reservoir. Upstream, the water rose so fast people’s houses were unmoored and afloat before they woke up. Clinging to rooftops, broken boards, and tree trunks, they rode the flood into the newly formed reservoir. It rose steadily until its weight broke the dam and tore down the overpass, crushing or drowning everyone trapped in the flush of water.

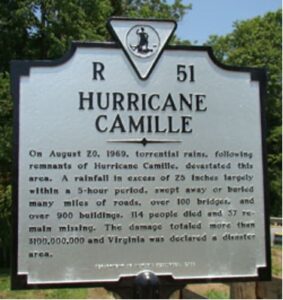

Camille hit Nelson County 56 years ago. My memories of it lay dormant until last fall when my brother-in-law made several trips from Charlottesville to Durham, North Carolina, to watch my granddaughter (his great niece) play soccer for Duke. He sent me a text message. “I drive by this sign a lot recently.” He attached a photograph of a Virginia historical road marker that commemorates Camille’s rampage through Nelson County.

Camille hit Nelson County 56 years ago. My memories of it lay dormant until last fall when my brother-in-law made several trips from Charlottesville to Durham, North Carolina, to watch my granddaughter (his great niece) play soccer for Duke. He sent me a text message. “I drive by this sign a lot recently.” He attached a photograph of a Virginia historical road marker that commemorates Camille’s rampage through Nelson County.

That marker brought back my memories of the storm, but it wasn’t the Fitzgerald family’s ordeal, Huffman Hollow, or the collapsed railroad bridge that first came to mind. It was a tangential personal connection.

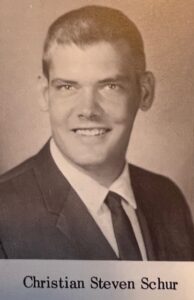

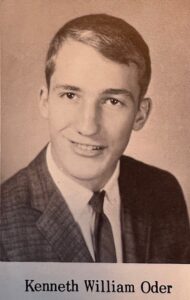

In 1965, when I was 18, my high school class went on a school trip to Washington, D.C. A classmate, Chris Schur, asked me to have lunch with him that day. I don’t know why he picked me. I barely knew him, and when we sat down at the lunch counter, he didn’t say much despite my attempts to draw him out.

In 1965, when I was 18, my high school class went on a school trip to Washington, D.C. A classmate, Chris Schur, asked me to have lunch with him that day. I don’t know why he picked me. I barely knew him, and when we sat down at the lunch counter, he didn’t say much despite my attempts to draw him out.

A few minutes into lunch, another classmate joined us, and he and I struck up a lively conversation. We tried to include Chris, but painfully shy, he could barely talk. His face reddened, and beads of sweat popped out on his forehead. After lunch, he wandered off by himself.

As far as I can recall, that was my last contact with Chris.

Four years later, a friend and I talked about the Nelson County flood. “You remember Chris Schur?” he said.

“Yeah. From high school.”

“His wife was killed in the flood.”

I didn’t know Chris’s wife and my only connection to him was that awkward lunch, but the news of his wife’s death hit me hard.

I didn’t know Chris’s wife and my only connection to him was that awkward lunch, but the news of his wife’s death hit me hard.

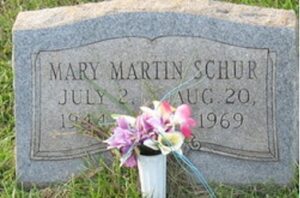

I searched for her obituary and found a brief entry in The Daily Progress. Mary Catherine Martin Schur died on August 20, 1969, of “multiple injuries and drowning.” She was a secretary for Vepco and a member of the Holy Comforter Church. Chris was an apprentice at a machine shop. They lived in Faber, Virginia. They’d been married eighteen months. Mary was 25 when she died. Chris was 24.

It took me a while to figure out why Mary’s death affected me so deeply. I remembered the introverted young man at the lunch counter, struggling to make conversation. I saw his tense face and those beads of sweat. Somehow, he had broken out of his shell and found someone to love, only to have her taken away from him. So tragic. So unfair.

I felt the need to reach out to Chris, but given that we barely knew each other, I could think of nothing that seemed appropriate. In the end, all I did was send flowers to the chapel holding Mary’s memorial service. “I am so sorry for your loss,” my note said. Hollow words from someone Chris probably didn’t remember.

Time passed. My concern for Chris faded away. Occasionally over the years, something would remind me of his loss, and the vague sense that I should have done more would nag at me, but for only a few moments.

Then came the Virginia road marker fifty-six years after the flood.

For reasons I don’t understand, this time thoughts about Chris wouldn’t go away. Wondering if he’d managed to put his life back together after Mary’s death, I searched for information on the internet. I couldn’t find much. Born in 1946, in Queens County, New York, Chris was a year older than my high school classmates, and he didn’t graduate with us. On my high school alumni website, he’s listed as a member of the class of 1966, so apparently, he was held back a year. An ancestry site indicates he never remarried after Mary’s death and he died in Palm Beach, Florida, in 2010 at age 64. That’s all I know.

For reasons I don’t understand, this time thoughts about Chris wouldn’t go away. Wondering if he’d managed to put his life back together after Mary’s death, I searched for information on the internet. I couldn’t find much. Born in 1946, in Queens County, New York, Chris was a year older than my high school classmates, and he didn’t graduate with us. On my high school alumni website, he’s listed as a member of the class of 1966, so apparently, he was held back a year. An ancestry site indicates he never remarried after Mary’s death and he died in Palm Beach, Florida, in 2010 at age 64. That’s all I know.

If any of my high school friends know anything more about Chris, I’d be interested in whatever you could tell me.

I’ve accumulated a few regrets over my long life. Most of them involve big screw-ups, but strangely, some of the small stuff that didn’t seem important when it went down still causes me minor discomfort, like little splinters under the skin of my thumb. They don’t hurt until I think about them, and even then, they don’t hurt much.

This little splinter won’t go away. I regret not reaching out to Chris. I wish I’d gone to his wife’s memorial service and spoken to him. I wish I’d been smart enough in 1969 to know that an expression of sympathy is never inappropriate in the face of overwhelming grief. I probably couldn’t have done anything for Chris, but I wish I’d tried. I just hope those close to him helped him find a path forward and his life turned out well.

This little splinter won’t go away. I regret not reaching out to Chris. I wish I’d gone to his wife’s memorial service and spoken to him. I wish I’d been smart enough in 1969 to know that an expression of sympathy is never inappropriate in the face of overwhelming grief. I probably couldn’t have done anything for Chris, but I wish I’d tried. I just hope those close to him helped him find a path forward and his life turned out well.

Post Script:

In Patrick Ryan’s novel, Buckeye, speaking about his state of mind in old age, Cal Jenkins says, “(Old people) aren’t living in the past; the past is living in us. And it’s talking. We get old to recalibrate everything we thought was going to be important. We get old just to hear it. It says, the days, the days, the days.”

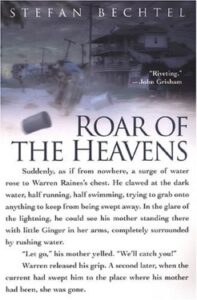

Stefan Bechtel’s Roar of the Heavens tells Camille’s many tragic stories. John Grisham, who now lives in Charlottesville, called the book riveting. I agree.

My trainer and good friend Janet called me one afternoon in July. “Marino says Lily is bleeding.” Her voice was tight, strained. “He says there’s a lot of blood.” Lily is a gray Azteca mare. Marino is the man who feeds my horses and mucks out the stalls.

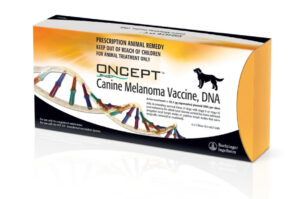

My trainer and good friend Janet called me one afternoon in July. “Marino says Lily is bleeding.” Her voice was tight, strained. “He says there’s a lot of blood.” Lily is a gray Azteca mare. Marino is the man who feeds my horses and mucks out the stalls. I lifted her tail. On its underside near the top, a black tumor the size of a crab-apple had burst and gushed blood.

I lifted her tail. On its underside near the top, a black tumor the size of a crab-apple had burst and gushed blood. Shortly after that, I found two small hard knots on her shoulder. Years earlier I’d seen growths like that on my dog. I knew what they were.

Shortly after that, I found two small hard knots on her shoulder. Years earlier I’d seen growths like that on my dog. I knew what they were.

In bed that night trying to find sleep, I couldn’t stop thinking about Lily. Life dealt her a cruel hand. Her previous owner’s abuse caused injuries to her shoulders and legs that never fully healed and contributed to the early onset of arthritis. Her gait is irregular, and she struggles on downhill grades. We give her medication daily to ease the pain.

In bed that night trying to find sleep, I couldn’t stop thinking about Lily. Life dealt her a cruel hand. Her previous owner’s abuse caused injuries to her shoulders and legs that never fully healed and contributed to the early onset of arthritis. Her gait is irregular, and she struggles on downhill grades. We give her medication daily to ease the pain. As I lay awake the night after Lily’s tumor burst, I couldn’t shake the feeling I was letting her down. I was cancer-free, but she was still trapped in its constricting grip.

As I lay awake the night after Lily’s tumor burst, I couldn’t shake the feeling I was letting her down. I was cancer-free, but she was still trapped in its constricting grip. In August, Janet called me over to Lily’s stall. “Something’s wrong,” she said.

In August, Janet called me over to Lily’s stall. “Something’s wrong,” she said.

“It wasn’t the tumors,” the vet said. “It was her teeth. If we’re lucky and the vaccine works, the tumors in her mouth won’t grow large enough to become a problem.”

“It wasn’t the tumors,” the vet said. “It was her teeth. If we’re lucky and the vaccine works, the tumors in her mouth won’t grow large enough to become a problem.”

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall.

I’d held my seat up to that point, but I expected her little bucks to escalate at any moment. I’d seen Marge bucking just for fun in her corral, kicking her back hooves in the air higher than her head, twisting to one side and then the other. No way I could stay on her back through those rodeo-bronco bucks. I braced for a bone-breaking fall. Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack.

Janet was riding Jackson about twenty yards ahead of Marge and me when the bees attacked. The trail dipped into a little swale lined with California live oaks. There must have been a beehive in those trees that Janet and Jackson stirred up when they went through. Coming along right after them, Marge and I bore the brunt of the attack. Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.”

Marge was too upset for me to ride her, so we led the horses down Long Valley Road to the barn. The whole way, Marge leaned against me, rubbing her face and neck against my shoulder. She was trying to ease the pain of the stings, but it also felt like she wanted my reassurance that we were safe. “Easy, girl,” I said again and again. “We’re okay now.” I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. (

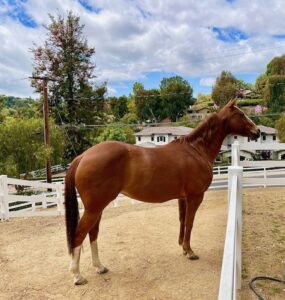

I took up horseback riding at the age of 70. ( I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring.

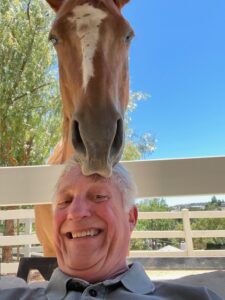

I learned the basics of horseback riding on Marge’s back. After that first ride, I rode Marge and no other horse almost every day for three months. I bought her from Janet that spring. She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair.

She won’t allow me to be in her presence without giving her my full attention, forever nudging and bumping my back and shoulder and rippling her lips over my arm. Sometimes, she even tries to groom my hair. I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her.

I ride five or six days a week. Of all my horses, I’ve clocked the most time on Marge, 700 rides over the last seven years being a conservative estimate. You develop a partnership with a horse over so many rides. Marge and I know each other well. I can tell what she’s thinking, and I feel like she knows what’s going on in my head. I talk to her sometimes, especially when I’m troubled. And for some magical reason, stress melts away when I’m with her. A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg.

A more serious health threat occurred one morning three years ago. When I arrived at the barn and opened the stall door, Marge lifted her right front hoof and extended it toward me. There was a deep slicing gash across her fetlock (similar to the human ankle). In the crevice of the cut, I could see bone. Blood had drained down over her hoof, and she couldn’t bear her full weight on that leg. The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.”

The day after the bee attack, I met Janet at the barn. “I’ve been thinking about yesterday,” Janet said. “Marge could have thrown you if she’d wanted to, you know. She let you stay on her back to protect you.” “That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said.

“That horse loves you, Ken,” Janet said.