The Downfall

On a cold clear day in January 1987, Wendell Blake was picking up trash in Siever Manufacturing’s Los Angeles plant parking lot at 9:30 a.m. when he heard the grating sound of metal scraping against metal and looked up to see a tall man he recognized from company town-hall meetings, walking between cars four rows away, leaning toward the car on his right with his arm down at his side. The scraping sound stopped when the man came to the rear of the car. He walked on through the lot to a gray Mercedes, climbed in, and drove away.

On a cold clear day in January 1987, Wendell Blake was picking up trash in Siever Manufacturing’s Los Angeles plant parking lot at 9:30 a.m. when he heard the grating sound of metal scraping against metal and looked up to see a tall man he recognized from company town-hall meetings, walking between cars four rows away, leaning toward the car on his right with his arm down at his side. The scraping sound stopped when the man came to the rear of the car. He walked on through the lot to a gray Mercedes, climbed in, and drove away.

Although Blake hadn’t actually seen the man’s hand come in contact with the car, he was certain he had keyed it. A closer look at the car confirmed his conclusion. A deep scar ran along its side from headlight to taillight.

It took Blake an hour to muster the courage to report what he’d seen to security.

The following week, Siever fired James Lockhart, its Chief Operating Officer, for vandalizing an employee’s car. Lockhart denied scratching the car and sued Siever. My law firm represented the company, and I was assigned to defend the case.

Lockhart’s personnel file glowed in the dark. He received uniformly excellent performance reviews throughout his 36 years with the company, climbing the corporate ladder steadily to become its second highest-ranking executive with a half-million-dollar annual salary.

Joyce Aguilar owned the scratched car, a blue 1984 Chevrolet Caprice. It was unmarked when she parked it in the lot the morning Lockhart walked by. Five employees had reported vandalism of their cars in Siever’s lot since the fall of 1986, all scratched in the same manner as Aguilar’s Caprice. All the employees, including Aguilar, worked in low-level jobs. None of them had ever dealt directly with Lockhart.

Lockhart’s work calendar confirmed he left the building the day in question at 9:30 a.m. to attend an off-site meeting and he was present at the plant when the other five cars were keyed.

Blake had worked for Siever for six years as a Custodian in the Maintenance Department. His personnel file was unremarkable: average ratings, no commendations, no discipline. He had never interacted with Lockhart.

I could find no motive for Lockhart to vandalize Aguilar’s car or for Blake to lie about him.

Ward Dunham, the CEO, made the decision to discharge Lockhart. “Blake was afraid he’d be fired for going against Jim,” he told me. “I admired him for coming forward, and I believed him. When I met with Jim, his angry denials didn’t ring true. Underneath his defensiveness, I sensed some sort of problem. I tried to get him to open up, but that only made him angrier. If he’d admitted the vandalism, we might have been able to work something out, but he wouldn’t give an inch. I felt I had no choice but to let him go.”

I questioned Blake in Siever’s conference room. A short stocky African American man, pushing forty, dressed in grease-smudged khaki work clothes, he answered my questions in a halting voice for an hour. I couldn’t shake his story.

I questioned Blake in Siever’s conference room. A short stocky African American man, pushing forty, dressed in grease-smudged khaki work clothes, he answered my questions in a halting voice for an hour. I couldn’t shake his story.

His answer to my last question was telling. “Why did you come forward, Mr. Blake?” I asked. “Why didn’t you lay low to stay out of trouble?”

He gave me a tired look. “The next car he scratched would be my fault much as him.”

I believed Blake.

I took Lockhart’s deposition. Sixty-two years old, six-feet-four with a mane of gray hair, dressed in a blue suit, white shirt, and yellow tie, he was a portrait of integrity. He said he’d worked long and hard to build a successful career at Siever. “The idea that I’d throw it all away to vandalize someone’s automobile is ludicrous.”

I believed Lockhart.

Something had to give. Either Blake was mistaken or Lockhart was mentally ill. It worried me that Blake hadn’t actually seen Lockhart’s hand pressing a key against the car. I had Blake take me to the parking lot and walk me through the incident. The facts and circumstances seemed conclusive. Based on what Blake saw and heard, Lockhart keyed the car.

I hired a private investigator to comb through Lockhart’s background. The first from his family to go to college, he joined Siever as an entry-level manager and excelled in every job he held as he rose to the top. He’d been happily married for 34 years and was active in church, community, and charitable organizations. If he was mentally ill, he hid it well.

Since I couldn’t convince myself Lockhart was lying even though Siever was paying me, I figured unbiased jurors might give him the benefit of the doubt. To avoid that risk, I decided to try to take the case away from the jury.

The law of wrongful discharge was evolving in California. Some courts implied a company could fire an employee only for “just cause,” an objective standard. Others held that a discharge decision was lawful if it was made in good faith. Under that standard, Lockhart’s termination might be lawful if Siever sincerely believed he keyed Aguilar’s car, whether or not he really did it.

Citing that case law, I filed a motion asking the judge to enter a judgment in Siever’s favor as a matter of law without a jury trial because there was no evidence Siever fired Lockhart for any reason other than its good faith belief he vandalized Aguilar’s car.

As I wrote the brief in support of the motion, I couldn’t answer the question that had nagged me since I took the case: Why would a powerful executive risk his career and good name to scratch the car of an employee he didn’t know?

At the hearing, while the judge grilled me about the limits of the good faith standard, I noticed him staring at Lockhart, sitting in the gallery. My nagging question troubles the judge, too, I thought. Convinced throughout oral argument that I was going down in flames, I was shocked when the judge granted my motion.

Lockhart’s lawyer was shocked, too. His Notice of Appeal hit my desk with lightning speed.

While the appeal was pending, the private investigator found an obscure misdemeanor conviction against Lockhart. In July, 1986, a Nordstrom’s store clerk caught him trying to shoplift a shirt and pair of slacks tucked under his jacket.

The similarity to the car vandalism was striking, a petty crime Lockhart had no reason to commit. That clinched it for me. As Ward Dunham had sensed, some sort of emotional problem lurked beneath Lockhart’s image of righteous probity.

It was too late to add the conviction to the record on appeal, so I put it in my pocket. If we were reversed and the case went to trial, I hoped to pull a Perry Mason and hit Lockhart with it on the witness stand.

I didn’t get the chance. The appellate court three-judge-panel ruled in Siever’s favor and Lockhart didn’t appeal the decision to the California Supreme Court. His years of service and age qualified him for a substantial pension despite his discharge, so he abandoned the case, took his retirement benefit, and moved to northern California’s wine country.

The case was closed. I’d secured the desired result, and Siever was pleased with my work. All was right with the world.

Then came the surprise that haunts me still. Over a six-week period in the spring of 1991, three months after Lockhart left Los Angeles, someone vandalized four cars in Siever’s parking lot. All were keyed in the same manner as the 1986–87 incidents with a deep scar running from headlight to taillight. One of the four cars scratched was Joyce Aguilar’s Chevy Caprice.

“I’m certain Jim vandalized the first set of cars,” Ward Dunham told me. “As far as I’m concerned, that shoplifting conviction removes all doubt. This new wave has to be the work of a copycat.”

I wasn’t so sure. Two things worried me: our case against Lockhart turned on a single eye witness; and the odds against different unrelated vandals randomly targeting Aguilar’s Chevy Caprice four years apart seemed astronomical. “It might be a good idea,” I told Dunham, “to watch Wendell Blake and Joyce Aguilar for a while.”

Siever put Aguilar and Blake under covert surveillance at work. They did nothing suspicious. Time passed. No new incidents occurred. Siever dropped its investigation, and the 1991 vandal was never identified.

Thirty-five years after I first opened the case file, I still worry that I helped destroy an innocent man’s career. Searching for reassurance as I wrote this, I found a surprising number of convictions of highly successful people for committing senseless small crimes. Most notoriously, the actress, Winona Ryder, shoplifted clothes and jewelry from Saks Fifth Avenue. Most of these people suffered from depression and repressed anger. Maybe Lockhart was such a person. If so, he betrayed no hint of it when I took his deposition in 1987, and in photos of his eighty-eighth birthday party posted on an old Facebook page, he still looked like a paragon of virtue, content and at peace with himself.

Who committed these crimes? Lockhart and a copycat? Blake? Aguilar? Or someone else? Maddeningly, I’ll never know for sure. Lockhart died peacefully at home in 2016 at the age of 91, taking the truth with him to his grave.

Post Script: To protect the privilege, I changed a few of the less important facts and the names of Lockhart, the company, and its employees.

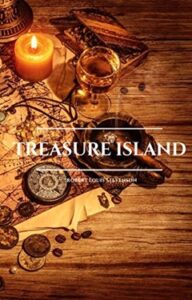

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

On my eleventh birthday, my aunt and uncle from Rhode Island sent me a package. I thought they were rich because their gifts never came out of the Sears catalog and they were always the best presents I got. I was crestfallen when I tore off the wrapping paper to find a book. I didn’t like to read. See Spot Run had turned me off early on. I’d never even read a short story, much less a whole book. I noticed that this one at least had an interesting cover, an artist’s rendering of old coins, a map, glass of rum, and compass strewn across an oaken table-top under the title: TREASURE ISLAND. Curious, I turned to the first page.

Standing on the tarmac, I looked up at the face of the jet. A basketball-sized gash dented the nosecone. Blood, entrails, and feathers covered the co-pilot’s windshield. Winnipeg is the capital of Manitoba, the Canadian province known as the land of a hundred thousand lakes. Thousands of geese flock to the lakes in the summer and pose a flight risk to aircraft on approach to the airport. The pilot said we were lucky. On one of her flights, a goose blew out the windshield and splattered innards all over the cockpit.

Standing on the tarmac, I looked up at the face of the jet. A basketball-sized gash dented the nosecone. Blood, entrails, and feathers covered the co-pilot’s windshield. Winnipeg is the capital of Manitoba, the Canadian province known as the land of a hundred thousand lakes. Thousands of geese flock to the lakes in the summer and pose a flight risk to aircraft on approach to the airport. The pilot said we were lucky. On one of her flights, a goose blew out the windshield and splattered innards all over the cockpit.