Against All Odds

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles.

In 1975, a smallish bay foal with a weak bloodline and a slightly backward arc at his knees was born at a thoroughbred breeding farm in Lexington, Kentucky. Months later, in January 1976, my son was born in Los Angeles.

On my son’s fifth birthday, his stomach was distended and he complained of nausea. Our pediatrician misdiagnosed it as a digestive problem. When the swelling spread to his face, arms, and legs, a team of doctors identified his illness as a rare condition where the kidneys strip protein from the system. Without protein, water seeps from the bloodstream into tissue and organs, causing swelling, which can lead to infections, blood clots, and kidney failure.

By the time they diagnosed his disease correctly, his survival was in question. After two miscarriages, Cindy was four months pregnant. To control the strain on her as best we could, I took the lead with my son’s crisis.

I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps.

I dropped everything and he and I moved into the Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles. The first night, his eyes swelled shut. I held him in my arms and tried to calm his fears. At dawn, diuretics mercifully flushed the water from his swollen face and he could see again, but the process didn’t stop there. The excretion of water continued for hours, relentlessly shrinking him down to a skeleton wrapped in pale gray skin as he screamed in pain from continuous muscle cramps.

When they’d purged all the stagnant water, the doctors built him up with injections of albumin. He would cry each time the doctor unveiled the needle. We tried to turn it into a game. “How long can you hold out before you cry? Bet you can’t make it all the way through the shot?” On day five, the doctor and I cheered when he took the injection without flinching.

His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not.

His improvement allowed him to sleep, so I wandered down the hall. I still can’t talk about the parents and kids I met, and with this post I’ve learned I can’t write about them either. The memories are too painful to confront. Survivor’s guilt plays a role, too. My son recovered. Many did not.

On the sixteenth day, they cleared my son to go home. In the discharge conference, the doctor said we still had a long way to go. His condition was chronic. Relapses are virtually inevitable. The steroid, prednisone, would help his kidneys function properly, but because of its harsh side effects, he could only take it in six-week intervals. After each cycle, his kidneys would perform normally for an indefinite time, then break down again. I was to test his urine daily. When he relapsed, we would resume the prednisone.

“How long will this last?” I asked the doctor.

“Most children carry the disease into their late teens, some into young adulthood. You must be vigilant. An undetected relapse can be as serious as the first episode.”

Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

Back at home, I gave my son the prednisone. It changed the shape of his face to resemble a cabbage patch doll with flushed chipmunk cheeks; he got chubbier; and he was moody and uncomfortable. After six weeks, we stopped the drug and his appearance and mood normalized. I tested his kidneys daily, dipping a plastic yellow stick in a urine sample. If it turned green, he was in trouble. Each day I was relieved when the stick stayed yellow, then immediately began worrying about the next one. I came to hate those sticks.

At the hospital, I’d learned a hard lesson. Time with my son was precious and irreplaceable. I vowed not to squander the second chance I’d been given. I volunteered to coach his soccer and T‑ball teams, signed up for Dodger season tickets, and planned weekend activities for us to share. On one of our outings that spring, we went to Santa Anita Park, a beautiful racecourse with manicured dirt and turf tracks and a grass infield. My son picked the horses; I placed our two-dollar bets; and we played catch on the grass between races.

In the eighth race, he picked number three. We went to the paddock where you can see the horses up close. Number three didn’t look like much. Sweating and foaming at the mouth, the undersized five-year-old bay gelding seemed nervous and unruly. We can kiss that two bucks goodbye, I thought.

From the bleachers, we watched three come from way back in the pack to pull ahead in the stretch and win by a half-length. We hugged and cheered, and for a short while, I forgot about the dark cloud hanging over us.

The following Monday, the stick turned gold; lime green the next day; then hunter green. We resumed the prednisone doses. The cabbage patch face, weight gain, and moodiness returned. Six weeks passed, and we stopped the drug again.

Cindy gave birth to our first daughter in June, and she became a second source of love and joy.

Another relapse came in July, followed by another round of prednisone.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.

The sticks were still yellow in November when my son and I returned to the racetrack. To my surprise, the bay gelding was entered in a major stakes race. He still didn’t look like much to me, but the betting crowd made him the prohibitive favorite and my son picked him again.

He started the race badly, falling ten lengths behind and staying there all the way down the backstretch. Seven lengths off the lead going into the last turn without much track to go, he seemed sure to lose.

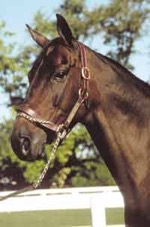

We stood on the rail about fifty feet from the finish line. I looked down the track and got a head-on view of him coming up the final stretch. I’ll never forget that snapshot image, forelegs pounding the turf like pistons, clods flying up behind him, wide glossy chest rippling with muscle, ears laid back, nostrils flared, head and neck pumping powerfully with each stride.

The track announcer’s bass voice boomed, “Here … Comes … John … Henry!” The crowd roared, and a chill went up my spine. He pulled ahead by a nose as he thundered by us and he buried the field by two lengths at the wire.

The gallery went wild. My son and I did, too. It was one of the most thrilling moments we’d ever shared.

Days passed into weeks, then months, and the sticks remained yellow. In August 1982, we reached the one-year mark without a failed test.

Complacency is your enemy, I told myself. Relapses are inevitable. You must be vigilant.

That fall we went to the track to watch John Henry run again. By that time, he was famous and even infrequent racetrack patrons like me knew his rags to riches story. With no pedigree, undersized, ill-tempered, and back at the knees, John Henry ran poorly as a young horse. A series of knowledgeable owners sold him for a song until Sam Rubin, a racing novice, bought him for $25000 sight unseen against a veterinarian’s negative recommendation. Frustrated with John Henry’s lackluster performances, Rubin fired his trainer, moved him to California, and placed him with Ron McAnally.

Known for his affection for his horses, McAnally and his staff bonded with the fractious bay gelding, training him with carrots, apples, and tender loving care. It worked.

In 1981, McAnally put John Henry up against the best horses in the world, and he won six major stakes races, including the two my son and I watched.

When my son and I returned to the track in the fall of 1982, he was seven years old, long in the tooth for a racehorse, but he hadn’t lost a step. He won that race with his patented, heart-pounding, come-from-behind charge, and my worries again fell away for at least a few moments as we joined the crowd’s frenzied cheering for The People’s Champion.

By the time the summer of 1983 rolled around, John Henry was still winning races, and my son kept testing yellow. In August, shortly after we passed the second anniversary of the last green stick, the doctor called me.

“No child has ever relapsed after two years of normal kidney function,” he said. “Very few children outgrow the disease before their teen years. Congratulations. Your son is now one of them.”

It took me a few moments to find my voice. “Thank you for everything.”

My son grew up to be strong and healthy. A successful businessman today, he’s married with two children and his kidney disease is a distant memory of a crisis that forged an iron bond between us.

After setting the lifetime purse-earnings record of $6,597,947 and winning every significant award in horse racing, John Henry retired at ten years old. A newspaper article celebrating his improbable success against all odds said he lifted the spirits and touched the lives of thousands of people. My son and I were two of them. He brought us thrills and joy when we needed them most, and his determined charges down the final stretch, running on pure heart and guts, refusing to give up, inspired me to persevere and gave me hope.

John Henry lived in the Hall of Champions at Lexington’s Kentucky Horse Park until his death in 2007 at age 32. It seems a touching twist of fate that the cause of death was kidney failure.

The duck glided to a smooth landing in our swimming pool last May. Wild-eyed and frothing at the mouth, our American Bulldog Zoey ran back and forth along the sandstone skirt barking frantically while the duck paddled lazy circles in the water just out of her reach. After taunting Zoey for an hour, she flew away. The next several mornings she returned and the same scene played out.

The duck glided to a smooth landing in our swimming pool last May. Wild-eyed and frothing at the mouth, our American Bulldog Zoey ran back and forth along the sandstone skirt barking frantically while the duck paddled lazy circles in the water just out of her reach. After taunting Zoey for an hour, she flew away. The next several mornings she returned and the same scene played out. She was right on both counts. I found the nest tucked under bushes behind the pool. It sealed my fate. Disturbing a duck’s nest is a criminal misdemeanor in California. Once she drops an egg, her squatter’s rights are absolute. She owns the place until she decides to leave.

She was right on both counts. I found the nest tucked under bushes behind the pool. It sealed my fate. Disturbing a duck’s nest is a criminal misdemeanor in California. Once she drops an egg, her squatter’s rights are absolute. She owns the place until she decides to leave. Then everything changed. The morning of June 10 the duck led seven little furballs into the water. I’d never seen a baby duck up close. I stood by the pool and stared at them for a long time.

Then everything changed. The morning of June 10 the duck led seven little furballs into the water. I’d never seen a baby duck up close. I stood by the pool and stared at them for a long time. The day after they were born, mama duck marched them across the yard to the frog pond. An hour later, I found her standing beside our rail fence on a hillside struggling to maintain her footing. Trapped between chain link stapled to the fence to keep the dogs inside and the fine-mesh net that keeps the rattlers out, a duckling hopped around like a ping pong ball. It couldn’t get out and mama couldn’t free it.

The day after they were born, mama duck marched them across the yard to the frog pond. An hour later, I found her standing beside our rail fence on a hillside struggling to maintain her footing. Trapped between chain link stapled to the fence to keep the dogs inside and the fine-mesh net that keeps the rattlers out, a duckling hopped around like a ping pong ball. It couldn’t get out and mama couldn’t free it. I fell, which on that steep grade was like jumping out of an airplane backwards without a parachute. The fall didn’t kill me solely because the only tree on the hill stood fifteen feet directly below me. I landed on it, impaled face up, its broken branches spearing my back. Spewing a string of curses, I climbed down stiffly and clawed my way back up the slope.

I fell, which on that steep grade was like jumping out of an airplane backwards without a parachute. The fall didn’t kill me solely because the only tree on the hill stood fifteen feet directly below me. I landed on it, impaled face up, its broken branches spearing my back. Spewing a string of curses, I climbed down stiffly and clawed my way back up the slope. In the morning, only four babies swam with mama. One of those I’d saved was gone. I spent the day searching the yard, the slope, and the neighbor’s yard, all to no avail.

In the morning, only four babies swam with mama. One of those I’d saved was gone. I spent the day searching the yard, the slope, and the neighbor’s yard, all to no avail. Weeks passed. The baby grew to half mama’s size with the brown-speckled markings of a female mallard. In August, she took wing on her maiden flight, glided south, and bank-turned back to the pool.

Weeks passed. The baby grew to half mama’s size with the brown-speckled markings of a female mallard. In August, she took wing on her maiden flight, glided south, and bank-turned back to the pool. She stayed with us through August and September.

She stayed with us through August and September. door to go out to the pool for a closer look, the female scurried out of the water, ran all the way across the yard, stopped in front of me, looked up, and cocked her head to one side. “Quack!”

door to go out to the pool for a closer look, the female scurried out of the water, ran all the way across the yard, stopped in front of me, looked up, and cocked her head to one side. “Quack!”

Fifty years later when a pair of polecats burrowed under our house in San Marino, I remembered the lessons of the Mount Moriah skunk invasion. To protect our furniture and clothing, I turned off the furnace and sealed off the duct vents, then made an urgent call to the animal control people. They referred me to a skunk specialist.

Fifty years later when a pair of polecats burrowed under our house in San Marino, I remembered the lessons of the Mount Moriah skunk invasion. To protect our furniture and clothing, I turned off the furnace and sealed off the duct vents, then made an urgent call to the animal control people. They referred me to a skunk specialist. At dawn, I awoke to enraged screams when the trap door fell, locking the skunks in the cage. Later that morning when the skunk guy threw a tarp over the steel box and carried it out to his truck, they screamed again. The cloud of spray enveloping him was as thick as coal dust and the stench was … well … there are no words. As he drove away, I wondered what it must be like to be him, to have no hope of ever going out on a date, making a friend, enjoying the companionship of a faithful pet, or even coming within shouting distance of any creature with olfactory glands.

At dawn, I awoke to enraged screams when the trap door fell, locking the skunks in the cage. Later that morning when the skunk guy threw a tarp over the steel box and carried it out to his truck, they screamed again. The cloud of spray enveloping him was as thick as coal dust and the stench was … well … there are no words. As he drove away, I wondered what it must be like to be him, to have no hope of ever going out on a date, making a friend, enjoying the companionship of a faithful pet, or even coming within shouting distance of any creature with olfactory glands. I tell you my history with skunks as a long-winded introduction to this month’s topic of controversy: Pepé Le Pew. Pepé is a cartoon skunk who starred in 17 Looney Tunes productions, making his debut in 1945 in Odor-able Kitty and winning an Oscar in 1949 for Scent-imental Reasons. Pepe’s character is modeled on Charles Boyer, a French cinematic heartthrob of the 1940’s. Most of Pepe’s films involve the same plot line. By accident a female cat ends up with a white stripe painted down her back. Pepe mistakes her for a skunk and falls in love. Blissfully oblivious to his repulsive odor, Pepé pursues the traumatized cat relentlessly while she desperately tries to fend him off.

I tell you my history with skunks as a long-winded introduction to this month’s topic of controversy: Pepé Le Pew. Pepé is a cartoon skunk who starred in 17 Looney Tunes productions, making his debut in 1945 in Odor-able Kitty and winning an Oscar in 1949 for Scent-imental Reasons. Pepe’s character is modeled on Charles Boyer, a French cinematic heartthrob of the 1940’s. Most of Pepe’s films involve the same plot line. By accident a female cat ends up with a white stripe painted down her back. Pepe mistakes her for a skunk and falls in love. Blissfully oblivious to his repulsive odor, Pepé pursues the traumatized cat relentlessly while she desperately tries to fend him off.

I have no clue what that means, but it doesn’t sound good, especially that last part.

I have no clue what that means, but it doesn’t sound good, especially that last part. I get that, but I don’t agree with the conclusions Charles and others draw from it – that Pepé teaches little boys no doesn’t really mean no and overcoming a woman’s strenuous objections is normal, adorable, and funny.

I get that, but I don’t agree with the conclusions Charles and others draw from it – that Pepé teaches little boys no doesn’t really mean no and overcoming a woman’s strenuous objections is normal, adorable, and funny. I confess, however, that I’m probably not an objective judge of Pepé’s character. I feel a certain kinship with him. When your last name is Oder, you endure a lot of taunting in elementary school. For a horrible few weeks in the third grade, I got saddled with the nickname Stinky. My little brother had it worse. In the second grade, the teacher assigned locker mates using the alphabetical order of their last names. In a cruel twist of fate, my brother’s locker buddy became Ronnie Pugh (pronounced “pew”). The Oder-Pugh locker took a lot of gas, so to speak. For those of us in the Oder clan, and probably for most of the Pughs, Pepé’s persistent confidence in the face of an overpowering social stigma gave us the strength to endure the witless slings and arrows of countless immature stupid jerks (not that we took it personally or hold a grudge or anything).

I confess, however, that I’m probably not an objective judge of Pepé’s character. I feel a certain kinship with him. When your last name is Oder, you endure a lot of taunting in elementary school. For a horrible few weeks in the third grade, I got saddled with the nickname Stinky. My little brother had it worse. In the second grade, the teacher assigned locker mates using the alphabetical order of their last names. In a cruel twist of fate, my brother’s locker buddy became Ronnie Pugh (pronounced “pew”). The Oder-Pugh locker took a lot of gas, so to speak. For those of us in the Oder clan, and probably for most of the Pughs, Pepé’s persistent confidence in the face of an overpowering social stigma gave us the strength to endure the witless slings and arrows of countless immature stupid jerks (not that we took it personally or hold a grudge or anything).