An American Hero

At 4:30 p.m. on November 12, 2004, a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) blew through a Black Hawk helicopter’s plexiglass chin bubble at the feet of its pilot, Captain Tammy Duckworth, and detonated in her lap, vaporizing her right leg, blowing her left leg up into the instrument panel, and shredding her right arm. The chopper went into a steep descent. Going in and out of consciousness, Duckworth grabbed the stick with her left hand and tried to guide the craft to a safe landing, but without legs she couldn’t press the floor-pedal controls.

At 4:30 p.m. on November 12, 2004, a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) blew through a Black Hawk helicopter’s plexiglass chin bubble at the feet of its pilot, Captain Tammy Duckworth, and detonated in her lap, vaporizing her right leg, blowing her left leg up into the instrument panel, and shredding her right arm. The chopper went into a steep descent. Going in and out of consciousness, Duckworth grabbed the stick with her left hand and tried to guide the craft to a safe landing, but without legs she couldn’t press the floor-pedal controls.

Co-pilot, Dan Milberg, uninjured in the blast, brought the chopper down safely in a small clearing about five minutes flight time from the Taji, Iraq, airfield. It hit the ground hard in an upright position, its rotor blades jolting to a stop. When Duckworth reached for the lever to shut off the engine, she passed out.

Behind Duckworth and Milberg in the cabin, the copter’s other two crew members were seriously injured. The RPG tore apart Sergeant Chris Fierce’s leg, and an AK-47 round hit door gunner Kurt Hannemann in the lower back.

Milberg knew they had to get out of there because the Iraqi insurgents, who shot them down from a grove of palms about 500 yards away, would be running as fast as they could to the clearing to finish them off.

In Iraq, Black Hawks flew missions in pairs. Milberg jumped out of the cockpit and frantically waved down the companion Black Hawk hovering overhead. It immediately landed in the clearing.

Hannemann stumbled out of the downed chopper. As the door gunner, his job was to “defend the perimeter” while the others made a run to safety. With the entire back of his uniform soaked in his own blood, lightheaded, and going into shock, the 23-year-old soldier staggered across the clearing and placed himself and his M4 between the choppers and the expected arrival point of the bad guys.

Milberg helped Fierce out of the Black Hawk and turned to Duckworth. Her listless body slumped forward into her shoulder harness, her right leg gone, her left leg sheared at the shin but hanging on by a thread of flesh, the skin and muscle of her right arm pulverized, its bones shattered, her torso and face riddled with hot shrapnel, blood drenching her uniform. Tammy’s dead, Milberg thought.

The American Soldier’s creed is unequivocal: “I will never leave a fallen companion.” Even a dead one.

Milberg pulled Duckworth’s lifeless body out of the cockpit. He and Matt Backues, of the rescue copter’s crew, draped her arms over their shoulders and ran for the waiting Black Hawk. She was so slick with blood they dropped her, picked her up, and dropped her again. Milberg then saw that Fierce couldn’t walk on his crushed leg and peeled off to help him while Backues grabbed the shoulder strap of Duckworth’s flight vest and dragged her across the clearing.

Hannemann retreated from the perimeter and climbed on board the rescue copter. Backues handed Duckworth’s torso up to him, and he lifted her into the cabin, her left leg flopping along behind, that thread of flesh still holding it on. The others scrambled in, and the Black Hawk took off.

As it sped toward Taji, Fierce stared at buckets of blood sloshing around on the floor. Where did all that blood come from? He’d applied a tourniquet to his mangled leg, and it had stopped bleeding. Hannemann’s wound had stopped bleeding, too. Suddenly, it dawned on him. Duckworth’s heart was still pumping. He shouted to the others that she was alive! The pilot radioed Taji to have a Medivac copter ready to speed her to the surgical hospital in Baghdad.

The Medivac touched down in Baghdad at 5:24 p.m., less than an hour after the RPG explosion. As the nurses transferred her to a mobile gurney, she regained consciousness. She remembered the shootdown, but nothing after that.

“Where are my guys?” she shouted.

“Just relax,” they told her. “We’ve got people taking care of them.”

But she wouldn’t relent, demanding information about the welfare of her crew all the way into the operating room. When a nurse began to give her anesthesia, she grabbed him by the scrub, pulled him to her, and looked him dead in the eyes. “You better take care of my guys!” she said. Then she fell back, and everything went black.

In 2010, I’d contributed time and money for a decade to Los Angeles Public Counsel, the nation’s largest pro bono law firm, representing more than 25,000 low-income children, adults, and families. In 2009, I helped Public Counsel launch a Center for Veterans’ Advancement to aid veterans overcome poverty, employment barriers, homelessness, and physical and mental health issues.

Each year Public Counsel throws a big fundraising banquet and gives an award to an individual who has made significant contributions to its causes. In 2010, Public Counsel gave its annual award to the United States Assistant Secretary of Veterans Affairs.

Because of my involvement with the Center, Public Counsel gave Cindy and me seats beside the honoree. When we arrived at the Beverly Hilton Hotel’s banquet room for the awards ceremony, the Assistant Secretary was already there, her wheelchair pushed up close to the head table. We sat down next to her and introduced ourselves.

“Tammy Duckworth,” she said, shaking our hands. “It’s an honor to meet you.”

She hadn’t received much press back then. I only knew bare-bones facts about her. Born in 1968 in Bangkok, Thailand, to a Thai-Chinese mom and a U.S. Army dad, and raised in Honolulu, Hawaii, she joined the Army in 1992 and became a helicopter pilot. After the RPG attack, she spent a year rehabilitating from her injuries in Walter Reed Hospital in Bethesda, Maryland. While there, she helped other patients secure benefits. That sparked an interest in government service on behalf of veterans, which eventually led to her appointment to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Flashing a pixie grin, upbeat, and fun to talk to, she gave me suggestions about the Center and some contacts who could help us, but she wasn’t all business. She asked about our children and beamed as we bragged on them. It was obvious she loved kids, but at 42, she was childless. I wondered if her injuries were the reason.

When they pulled her chair away from the table to wheel her backstage for the award presentation, I saw the extent of those injuries for the first time. Her right leg was amputated up high near the hip; her left leg was gone just below the knee; and her right arm was laced with fleshy skin grafts.

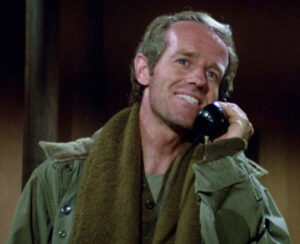

Mike Farrell, a U.S. Marine Corps veteran and the actor who played Hawkeye’s sidekick on M*A*S*H, introduced her. She emerged from behind the curtains, walked across the stage on prosthetic legs, and took her place behind the lectern, maintaining that pixie grin all the way.

Speaking without notes in a conversational tone, she talked about the shootdown, focusing on the heroics of the 23-year-old door gunner, Kurt Hannemann. Scared out of his mind, in great pain, and bleeding profusely, he put his life at risk, she said, to defend the perimeter and protect the crew. Public Counsel makes that same stand, she told us. “You represent the voiceless, the powerless, the poor, and the disabled. You’ve been running to the fight for years, making a stand, saying ‘You’re not getting through me. I’m here to defend these people and the values I believe in.’” She emphasized the importance of our work for veterans. “Tonight, there are young brave American men and women strapping on body armor right now. They need to know you’re on that perimeter. They need to know you’ll be here to help them when they return.”

She almost died defending her country. For most of us in the audience, our only sacrifice was writing checks and volunteering in our spare time, and yet she closed her remarks by thanking us for our service to the nation.

I’ll never forget that speech. This courageous soldier, who lost both legs, a big chunk of her right arm, and half the blood in her body, stood before a crowd of rich lawyers dressed in thousand-dollar suits and silk ties, sitting in the lap of luxury in Beverly Hills, our bellies full from a banquet fare of filet mignon and chocolate souffle, and made us feel like we were the real heroes. Her grace, bravery, and good humor made me want to give back so much more.

As Mike Farrell said at the end of the ceremony, “By God, she’s inspiring!”

Tammy Duckworth is now the junior Senator from Illinois.

I’m glad I was wrong about her injuries. In 2014 at age 46, she had a baby girl, and in 2018 at age 50, she became the first Senator to give birth while in office, another baby girl.

I’m glad I was wrong about her injuries. In 2014 at age 46, she had a baby girl, and in 2018 at age 50, she became the first Senator to give birth while in office, another baby girl.

In 2020, she made the short list of potential running mates for Joe Biden, but he worried that Republicans would attack her eligibility because she was born in Thailand. “I’ve beaten every asshole who’s come after me with that,” she told Biden. He chose Kamala Harris instead. I can’t help wondering what course history would have taken if he’d chosen Senator Duckworth.

Political pundits say that Democrats are searching desperately for a leader and that those who have stepped forward so far haven’t generated much enthusiasm. Senator Duckworth’s name never comes up.

I don’t write political posts, mainly because politics makes me sick (see Political Angst for more on that), but I’ll break my rule here to say this.

I don’t write political posts, mainly because politics makes me sick (see Political Angst for more on that), but I’ll break my rule here to say this.

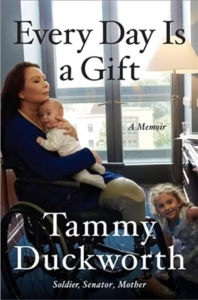

The epigraph to Senator Duckworth’s 2021 memoir, Every Day is a Gift, is the U.S. Army Warrior Ethos: “I will always place the mission first. I will never accept defeat. I will never quit. I will never leave a fallen comrade.”

If you’re looking for a leader, you might want to consider an American hero, who has lived her whole life by that creed.

A horse lay on his side on the pavement at the intersection of Clear Valley Road and Long Valley Road. He wore the signs of old age, a scruffy brown coat, bloated girth on a skinny frame, protruding ribs and hip bones. A crowd of about 20 people had gathered around him. A man pulled on his reins while others pushed him and prodded him. “Come on, Papa! Up now! Get on up! Up you go!” The old horse lifted his head feebly, let it fall back to the concrete, and heaved a long slow breath.

A horse lay on his side on the pavement at the intersection of Clear Valley Road and Long Valley Road. He wore the signs of old age, a scruffy brown coat, bloated girth on a skinny frame, protruding ribs and hip bones. A crowd of about 20 people had gathered around him. A man pulled on his reins while others pushed him and prodded him. “Come on, Papa! Up now! Get on up! Up you go!” The old horse lifted his head feebly, let it fall back to the concrete, and heaved a long slow breath. Wearing riding breeches and boots, a gaunt woman with close-cropped dark hair and tattooed arms stood over the horse, scowling. “There’s nothing wrong with him,” she said. “He’s stubborn. He just doesn’t want to get up.”

Wearing riding breeches and boots, a gaunt woman with close-cropped dark hair and tattooed arms stood over the horse, scowling. “There’s nothing wrong with him,” she said. “He’s stubborn. He just doesn’t want to get up.”

The vet looked Casey over. “First thing we have to do is get him up.”

The vet looked Casey over. “First thing we have to do is get him up.”

I was reading Paulette Jiles’ novel, Stormy Weather, the day I learned Casey had passed. That night I came to the part where Ross Everett advises his girlfriend not to become emotionally invested in her horse, Smoky Joe. “Don’t get attached to a horse, Jeanine. We always outlive them. Except the last one.” I set the book aside and thought about that passage.

I was reading Paulette Jiles’ novel, Stormy Weather, the day I learned Casey had passed. That night I came to the part where Ross Everett advises his girlfriend not to become emotionally invested in her horse, Smoky Joe. “Don’t get attached to a horse, Jeanine. We always outlive them. Except the last one.” I set the book aside and thought about that passage.

Opening Day, 1981 T‑ball season. Yankees v. Red Sox. Top of the first inning.

Opening Day, 1981 T‑ball season. Yankees v. Red Sox. Top of the first inning. “Fielder’s crouch,” Arnold said to Arlo. Arlo bent his knees and pounded his fist into his glove.

“Fielder’s crouch,” Arnold said to Arlo. Arlo bent his knees and pounded his fist into his glove. The third baseman, Robby, a drifty towheaded kid, stood on third base at parade rest, grinning vapidly at a pigeon flying over right field.

The third baseman, Robby, a drifty towheaded kid, stood on third base at parade rest, grinning vapidly at a pigeon flying over right field.