The Witness

Just as I walked out of a tropical fish shop on Melrose Avenue in Hollywood, a van plowed head-on into the grill of a small car right in front of me. This was in the late 70’s before car seats and airbags, so I expected the worst as I ran over to the crash. A young mother sat behind the wheel of the car, bleeding from a deep gash to her forehead. A little boy lay on the floorboard in front of the passenger seat, crying. I pulled the mom out, handed her off to a woman standing on the sidewalk, and went back for the little boy. By that time a man wearing a khaki cargo jacket had picked him up and carried him to a bus stop bench. The boy seemed stunned, but uninjured. Others tended to the driver of the van, an elderly man, clutching his chest. A fire engine and an ambulance arrived, and the rescue workers took over.

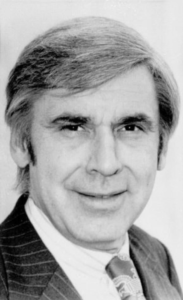

I sat down on the bench to pull myself together. The man wearing the cargo jacket sat next to me. We talked about the accident. About all I remember about our conversation was that he mentioned he was a camera man for NBC. Afterwards, we went our separate ways, and I forgot about him.

A few months later, I was watching the nightly news when photographs of four men appeared on the television screen. One of them looked familiar. The reporter identified him as Bob Brown. When she said he was an NBC camera man, I recognized him as the man I had met at the accident.

A hollow place opened in the pit of my stomach as she reported that followers of the cult leader, Jim Jones, had murdered the four men and that Brown had filmed his own execution.

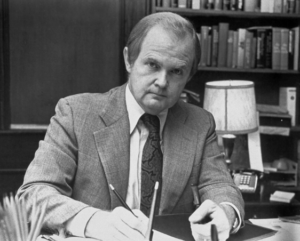

In the following days, the press didn’t provide much information about Brown, focusing instead on the main characters in the bizarre story that led to the murders: Jim Jones and Congressman Leo Ryan.

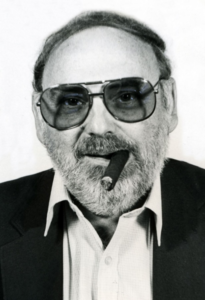

Jones was an ordained Disciples of Christ pastor. He founded the People’s Temple in Indiana and eventually moved it to San Francisco. He attracted a national audience and garnered the support of influential Bay Area politicians, like Willie Brown and Harvey Milk.

In the mid-70’s, he became delusional, announcing that he was the incarnation of Jesus, Gandhi, Buddha, and Vladimir Lenin, but thousands of his church members remained loyal to him. In 1977, he moved the People’s Temple to Guyana, a small country on Brazil’s northern border. By 1978, 1100 church members had followed him there to live in a settlement dubbed Jonestown.

Rumors that Jones would not allow dissenters to leave the settlement and allegations of sexual abuse and torture soon reached relatives of the People’s Temple congregation. Frustrated that the State Department would not address these claims, a Bay Area Congressman, Leo Ryan, put together a fact-finding team to go to Jonestown. The group included Jackie Speier (then Ryan’s legislative assistant, now a member of Congress), several reporters, and an NBC camera crew led by Bob Brown.

Brown turned down the trip at first. His friends later said he had a premonition that he would die there, but NBC persuaded him to go.

Forecasting the great risk posed by the trip didn’t require clairvoyance. Jones had built Jonestown in a remote, isolated area. The only way in was to fly a small plane from Georgetown, Guyana’s capital, to a dirt airstrip near Port Kaituma, and then travel by truck through the jungle for an hour and a half. Jones’s loyalists were heavily armed. Ryan’s delegation consisted of eighteen unarmed civilians with no security detail.

Ryan’s party arrived in Guyana on November 14, but Jones wouldn’t allow them to visit the settlement until the 17th. The tension between Jones and Ryan’s delegation is palpable in that day’s videotaped scenes recovered from Brown’s camera after his murder. That afternoon, someone slipped a note to Ryan: “Please help us get out of Jonestown.” Fifteen people eventually stepped forward to say they wanted to leave. Ryan negotiated with Jones about their departure, and he gave his consent reluctantly.

The next day, Ryan’s team and the defectors returned to the airstrip to board two small planes bound for Georgetown. One of the defectors turned out to be a plant. He pulled a gun and began shooting at the others. At the same time, a truck sped onto the airstrip carrying riflemen, who opened fire on everyone in Ryan’s party.

Brown stood at the tail of one of the planes when the shooting began. He immediately raised his camera and moved toward the gunmen. Reporter Ron Javers said, “I was knocked to the ground by a slug in the left shoulder … Bob Brown stayed on his feet and kept filming even as the attackers advanced on him… He was incredibly tenacious.” They shot Brown in the thigh, and he fell to the ground, still taping, as one of the riflemen approached him and shot him in the face at point blank range. The videotape recovered from his camera flickers and goes blank, presumably at that moment.

Four others were killed, including Ryan. Ten were wounded. The survivors played dead or ran into the jungle. The pilots fled in the airplanes, and the gunmen sped back to the settlement. The wounded, including Jackie Speier, who had been shot five times, had to wait 22 hours for help to arrive.

The afternoon of the attack, 909 Temple people died clustered around Jonestown’s main pavilion. The FBI recovered an audiotape of Jones telling them that hostile forces would take revenge for the murders. Men will “parachute in here on us … shoot some of our innocent babies … and torture our children.” He convinced them to commit “revolutionary suicide” by drinking cyanide-laced Kool-Aid. The adults gave the Kool-Aid to 304 children and then drank it themselves. Jones’s corpse was found wedged between two bodies, a gunshot wound to his temple, apparently self-inflicted.

Most of the subsequent coverage concentrated on the mass suicide, Jones, and Ryan. Reports about Ryan’s murder sometimes mentioned Brown in passing, but the press published very few details about his background. All I could find was that he was 36 when he was killed, he’d been a TV reporter in LA before switching to photojournalism, and he was known among his colleagues for human interest stories.

Eye witnesses to his death are uniform in their praise for his courage. Others ran away when the shooting began, but he advanced on his murderers without hesitation, lens up. He had to know they would kill him, but he never wavered. It seems clear he made a conscious decision to sacrifice his life to make sure the world would know what took place on the airstrip that day.

Honors were bestowed on him in the months following his death. NBC set up a display about the massacre in its New York offices that reads in part: “Showing extraordinary bravery, cameraman Bob Brown recorded the attack, perhaps even the shot that killed him.” San Francisco State University established the Bob Brown Memorial Scholarship for Journalists. And President Carter presented a posthumous dedication to Brown and two other press members at the 1979 Emmy Awards show. “It is no accident,” he said, “that the root meaning of the word ‘martyr’ is ‘to witness’ … (T)hese men were our witnesses.”

Shortly after the tributes, Brown’s name and story faded from public awareness. Today, almost no one knows who he is or what he did.

I’ve tried over the years to recall more about him, but I can barely remember him. You experience brief encounters with thousands of people over a long life. Most of them fade from memory within days, if not hours. This one seemed no different. I met an ordinary guy on Melrose one day, friendly enough, but unremarkable.

Or so I thought at the time.

The morning of my knee replacement surgery, my wife and I drove along Medical Center Drive at 5:30 a.m. When we turned into the West Hills Hospital parking lot, the headlights washed over a teenage boy wearing a pair of white boxer shorts, a blue bath towel tied around his neck, and nothing else, running along the sidewalk, laughing maniacally, tilting his outstretched arms back and forth like a big bird banking in the wind. We watched him sprint across the lot to the bus stop on Sherman Way, his shoulder length black hair and the towel fanning out behind him, his knees pumping, his bare feet slapping the asphalt.

The morning of my knee replacement surgery, my wife and I drove along Medical Center Drive at 5:30 a.m. When we turned into the West Hills Hospital parking lot, the headlights washed over a teenage boy wearing a pair of white boxer shorts, a blue bath towel tied around his neck, and nothing else, running along the sidewalk, laughing maniacally, tilting his outstretched arms back and forth like a big bird banking in the wind. We watched him sprint across the lot to the bus stop on Sherman Way, his shoulder length black hair and the towel fanning out behind him, his knees pumping, his bare feet slapping the asphalt.