The Nekkid Breakfast

The telephone rang. “Law offices. Oder.”

The telephone rang. “Law offices. Oder.”

“Kenny, it’s Sue Ellen. You ain’t gonna believe what just happened! Fred came to the breakfast table buck nekkid! Larry and Grady were still in bed, thank you, Jesus! It’s a miracle they didn’t wake up and walk in the kitchen! Can you imagine the shock of my little boys seein’ their daddy nekkid as a jaybird?”

In her mid-twenties, short and slight with coal-black eyes and stringy brown hair, born-again Christian, mother of two boys, and the unhappy wife of a motorcycle enthusiast and serial sinner, Sue Ellen Defibaugh called me every day for three weeks. Each call went on forever; she rarely paused to take a breath; and I couldn’t jam a word in edgeways.

“Sue Ellen –”

“I told Fred to march right back in the bedroom and get dressed and he just sat at the table with his hands between his nekkid legs and his head hangin’ down and he started cryin’ and he said Sue Ellen you gone crazy with Jesus and I can’t stand it and I want you to go back to the way you was and I said Jesus is my Lord and Savior and you need to get straight with Him because I can’t live with a sinner who cusses and drinks whiskey and listens to the devil’s music and comes to breakfast nekkid.”

“I told Fred to march right back in the bedroom and get dressed and he just sat at the table with his hands between his nekkid legs and his head hangin’ down and he started cryin’ and he said Sue Ellen you gone crazy with Jesus and I can’t stand it and I want you to go back to the way you was and I said Jesus is my Lord and Savior and you need to get straight with Him because I can’t live with a sinner who cusses and drinks whiskey and listens to the devil’s music and comes to breakfast nekkid.”

Fred came to breakfast nekkid in the summer of 1972. UVA had accepted my application to law school the previous spring, and I gave notice to Albemarle County that I wouldn’t return in the fall for a fourth year of teaching high school. The news leaked out to my students. The father of one of them recommended me to a Charlottesville attorney, Richard Bell, who was looking for a summer clerk. I scheduled an interview.

Bell had converted a two-story residential home on a tree-lined street near the courthouse into law offices. Five-feet-four with a round face, receding chin, and little pot belly, he sat at his desk in what was once a large parlor and squinted at me through smudged, thick-lensed glasses.

Bell had converted a two-story residential home on a tree-lined street near the courthouse into law offices. Five-feet-four with a round face, receding chin, and little pot belly, he sat at his desk in what was once a large parlor and squinted at me through smudged, thick-lensed glasses.

“I haven’t even started law school,” I told him. “I don’t know anything about the law.”

“I don’t care,” he said. “Your students say you’re a people person. I need a people person.” He hired me on the spot.

My first day on the job, Jody Sprouse, Bell’s office manager, a no-nonsense pit bull in her fifties with a bee-hive of blue hair, led me to a closet-sized windowless room and plopped a stack of manila file folders on a dusty desk jammed against the back wall. “Your job,” she said, “is to keep these people away from Mister Bell.”

My first day on the job, Jody Sprouse, Bell’s office manager, a no-nonsense pit bull in her fifties with a bee-hive of blue hair, led me to a closet-sized windowless room and plopped a stack of manila file folders on a dusty desk jammed against the back wall. “Your job,” she said, “is to keep these people away from Mister Bell.”

By the end of the day, I understood why Bell needed a people person. He made a small fortune buying run-down homes in distressed neighborhoods and renting them out to cover the mortgage payments. The bulk of his legal work involved these transactions. While his acquisitions created substantial net worth, they didn’t generate much cash flow, so he took on traditional legal work to pay the bills. And that was the rub. Socially inept, taciturn, and sullen, he hated client contact.

Bell’s three law clerks were no help to him on that score. They were each brilliant UVA law students with the personality of a plastic bag. While they were great at legal research and documenting complex transactions, he couldn’t put them in a room with a client without losing the business.

Bell’s three law clerks were no help to him on that score. They were each brilliant UVA law students with the personality of a plastic bag. While they were great at legal research and documenting complex transactions, he couldn’t put them in a room with a client without losing the business.

That’s where I came in. The files Jody stacked on my desk spanned the spectrum of a sole practitioner’s bread and butter – wills, trusts, contract disputes, debt collection, divorce petitions. Each file contained Bell’s cryptic notes from an initial client meeting and a list of information he needed from them to complete their legal project.

My job was to meet with the clients, gather facts, fill in the blanks on form documents, and hand them off to Bell for final revision and court filings. I made a hit with the clients right off the bat. Angry because they’d been neglected, they immediately warmed up when I told them their case was my top priority. I was the people person; Bell was the lawyer; and everything went along smoothly.

Until one morning in July. Jody buzzed me. “Sue Ellen Defibaugh on line 2.”

I dug out a thin file labeled Defibaugh v. Defibaugh, containing a single page of pencil-scribbled phrases. “Pregnant at 16. Married 17. Second child 18. Husband won’t go to church.” Not much to go on, but by then I’d learned to dance without music. “Put her through,” I told Jody.

“Be careful. This woman’s crazy as a shithouse rat.”

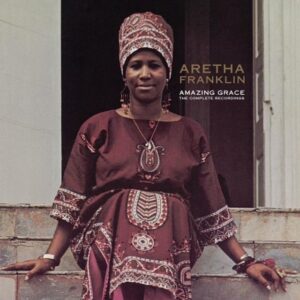

When I introduced myself, Sue Ellen cheered. At a revival service my dad preached in Free Union, she’d answered his altar call to dedicate her life to Christ. “Thank you, Jesus, for sendin’ me Reverend Oder’s son in my time of need!” She launched into a full-throated condemnation of Fred for pressuring her to stop playing “Jesus records.” The Blackwood Brothers, Jimmy Swaggart, Jimmy Patton, The Inspirations. Even Elvis and Aretha Franklin got into the act. “I cry every time that girl sings Amazin’ Grace.” After an hour without a pause, she hung up because she had to go to the toilet.

For three weeks, Sue Ellen buried me in an avalanche of phone calls. Fred wouldn’t go to church, drank beer, took the Lord’s name in vain, blasphemed, looked at dirty magazines, played poker with his buddies. Worst of all, he pestered Sue Ellen constantly about sex, but after my dad’s revival service, she’d refused to let him touch her. “It’s a sin to lie down with a man who don’t love our Lord and Savior!”

For three weeks, Sue Ellen buried me in an avalanche of phone calls. Fred wouldn’t go to church, drank beer, took the Lord’s name in vain, blasphemed, looked at dirty magazines, played poker with his buddies. Worst of all, he pestered Sue Ellen constantly about sex, but after my dad’s revival service, she’d refused to let him touch her. “It’s a sin to lie down with a man who don’t love our Lord and Savior!”

The nekkid breakfast came along in August, and it went bad in a hurry.

“When I told Fred to go back in the bedroom and pull on his pants, he stood up and said Sue Ellen I miss you so much and he just stood there cryin’ with big ole tears streamin’ down his face and he walked back in the bedroom real sad and I called you cause I want Mister Bell to get him outa my life unless he stops his sinnin’ ways–”

In the background I heard shouting and glass breaking.

I sat up straight. “Sue Ellen?!!”

“Sweet Jesus! Fred threw a chair through the window, jumped out, and drove off on his Harley. He ain’t wearin’ no shirt, but at least he put on his pants. I just don’t know what to do.” She broke down, sobbing.

“Sweet Jesus! Fred threw a chair through the window, jumped out, and drove off on his Harley. He ain’t wearin’ no shirt, but at least he put on his pants. I just don’t know what to do.” She broke down, sobbing.

Relieved Sue Ellen hadn’t been hurt, I let out a long breath.

“Oh no!” She gasped. “Larry and Grady is up. Merciful Jesus, please give me the brains to know what to tell my sweet babies.” The line clicked.

I placed the phone in its cradle and stared at it. Fred’s frustration was building. Something bad could happen any day now, and I didn’t know how to stop it.

As Jody and Bell had made abundantly clear, my job was to keep the clients away from him, especially the aggravating ones, and Sue Ellen was among the most aggravating clients God and my dad had ever called to the altar. But I was just a glad-handing people guy. She needed a lawyer.

Knowing I’d likely lose my job, I marched past a startled Jody into Bell’s office unannounced.

He looked up from a plat map and scowled. “What do you want?”

Jody stormed in behind me. “What do you think you’re doing? You can’t just barge in here—”

“I’m in over my head,” I said. “Sue Ellen Defibaugh’s safety is at risk.” I recapped her 35 phone calls, concluding with the nekkid breakfast and the smashed-out window.

When I finished, Bell stared at me silently for a long time. I expected the axe to fall at any moment.

When I finished, Bell stared at me silently for a long time. I expected the axe to fall at any moment.

Then Bell said, “Her husband called in here once. He told me he loved her. He cried. I felt sorry for him.” Bell put his hand to his receding chin, looked out the window, then looked at me. “The husband is unrepresented. Let’s call them in. I’ll meet with him while you meet with Mrs. Defibaugh. We’ll try to settle their differences.”

Her mouth hanging open, Jody looked like she might faint. I was shocked, too. The last thing either of us had expected was for Bell to propose meeting with a human being unrelated to his real estate business.

The next morning, Jody led Fred, a tall, muscle-bound, skinhead in his 20’s, wearing a leather jacket with a motorcycle helmet dangling from his hand, into Bell’s office.

I met with Sue Ellen in a conference room down the hall. “Is there any way you and Fred can stay together?” I asked her.

Sweaty chestnut-brown bangs sticking to her forehead, dark circles under her slightly crazed black eyes, she nodded eagerly. “All I want is for Fred to give his life to Christ.”

“Suppose he won’t do that.”

“Then I want him gone.”

I tried to talk her off that hard line. She wouldn’t give an inch. I interrupted Bell’s meeting with Fred and told them what she said. Fred asked to speak with Sue Ellen alone. She refused.

Bell met with Fred again while I waited with Sue Ellen. Fred told Bell the nekkid breakfast was his desperate attempt to resurrect the wild sexpot he’d fallen in love with, and although it didn’t work, he still loved her. It took Bell more than an hour to convince him to let her go.

Fred agreed to move out that day before Sue Ellen got home. Sue Ellen and I watched him from the conference room window. Tears streaming down his stone-hard face, he put on his helmet, straddled the Harley, and roared out of Bell’s parking lot.

Fred agreed to move out that day before Sue Ellen got home. Sue Ellen and I watched him from the conference room window. Tears streaming down his stone-hard face, he put on his helmet, straddled the Harley, and roared out of Bell’s parking lot.

“Good riddance,” Sue Ellen said, her eyes dry.

Later that afternoon, Jody came to my office. “What did you do to Mister Bell?” she said in a small voice.

“What do you mean?”

“When you were with Sue Ellen, he called me in his office to bring him a box a Kleenex. That big bald-headed boy was cryin’ like a baby and Mister Bell was huggin’ him.” She took a deep breath. “And he had tears in his eyes. What did you do to him?”

“I didn’t do anything. I don’t understand it either.”

Over the next few weeks, Bell and I worked out a separation agreement between Sue Ellen and Fred, dividing their property and giving him visitation rights. Their divorce petition was granted the following summer.

Over the next few weeks, Bell and I worked out a separation agreement between Sue Ellen and Fred, dividing their property and giving him visitation rights. Their divorce petition was granted the following summer.

I worked for Bell nights and weekends throughout my law school days. During that time, I came to understand him better. We were very different people, but like-minded in two ways: 1) after Defibaugh v. Defibaugh, we both vowed never to come within a country mile of another divorce case; and 2) although Bell worked hard to conceal it, he was a good people person. When it counted most, he listened to his heart.

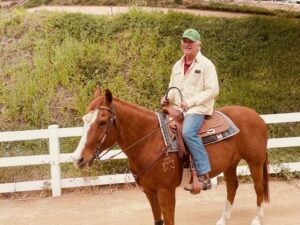

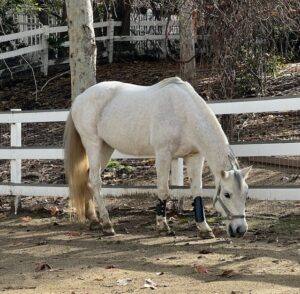

I first saw her in a photograph posted on a website about horses for sale in Southern California. I had bought a little sorrel mare, Marge, and I was in the market for a stablemate when my trainer and good friend, Janet, saw an advertisement on the internet and sent me the link.

I first saw her in a photograph posted on a website about horses for sale in Southern California. I had bought a little sorrel mare, Marge, and I was in the market for a stablemate when my trainer and good friend, Janet, saw an advertisement on the internet and sent me the link. I parked in front of a pale yellow, tile-roofed home. A short guy in his late thirties wearing a cowboy hat, jeans, and boots, stood on the front stoop. We talked while we waited for Janet. His name was Miguel. He worked as a leadman on an assembly line in one of the aerospace factories that form the backbone of Lancaster’s economy. He bought the horse from a friend when she was two years old. He didn’t have time to work with her anymore because he was busy coaching his sons’ Little League teams. He seemed like a nice guy, a good father trying to raise his kids right.

I parked in front of a pale yellow, tile-roofed home. A short guy in his late thirties wearing a cowboy hat, jeans, and boots, stood on the front stoop. We talked while we waited for Janet. His name was Miguel. He worked as a leadman on an assembly line in one of the aerospace factories that form the backbone of Lancaster’s economy. He bought the horse from a friend when she was two years old. He didn’t have time to work with her anymore because he was busy coaching his sons’ Little League teams. He seemed like a nice guy, a good father trying to raise his kids right. When Janet got there, we walked around behind the house. A saddled and bridled gray horse stood under a big shady ash tree next to a corral. A chain hooked to her halter and tied to a branch high above her head was pulled taut, forcing her to hold her head tilted upward. Her big eyes watched us as we approached. The look in her eyes and the tension in her stance made me uneasy.

When Janet got there, we walked around behind the house. A saddled and bridled gray horse stood under a big shady ash tree next to a corral. A chain hooked to her halter and tied to a branch high above her head was pulled taut, forcing her to hold her head tilted upward. Her big eyes watched us as we approached. The look in her eyes and the tension in her stance made me uneasy.  “You don’t need to do that!” Janet shouted. “We’re only looking for a trail horse.”

“You don’t need to do that!” Janet shouted. “We’re only looking for a trail horse.” The split personality confused me at the time, but since then, I’ve met many horsemen like Miguel, nice people in most aspects of their lives, but with a blind spot about horses. They treat them like inanimate tools with no thoughts, feelings, or emotions, like a tractor or some other type of farm machinery. They expect horses to follow the dictates of their will without the slightest deviation. When a horse resists, they beat her into submission, and when she can no longer perform, they don’t hesitate to put her down.

The split personality confused me at the time, but since then, I’ve met many horsemen like Miguel, nice people in most aspects of their lives, but with a blind spot about horses. They treat them like inanimate tools with no thoughts, feelings, or emotions, like a tractor or some other type of farm machinery. They expect horses to follow the dictates of their will without the slightest deviation. When a horse resists, they beat her into submission, and when she can no longer perform, they don’t hesitate to put her down. Janet exploded and bawled Miguel out. I thought he’d get mad, but his blind spot about horses left him puzzled, rather than offended. He shrugged off her anger and turned to me. “So how about it? Do you want to buy the horse?”

Janet exploded and bawled Miguel out. I thought he’d get mad, but his blind spot about horses left him puzzled, rather than offended. He shrugged off her anger and turned to me. “So how about it? Do you want to buy the horse?” I looked over at the horse. Her soulful eyes stared back at me. Something stirred inside my chest. I agreed with Janet’s assessment, but I couldn’t leave her there. “I’d pay double the asking price,” I said, “just to get her away from this guy.”

I looked over at the horse. Her soulful eyes stared back at me. Something stirred inside my chest. I agreed with Janet’s assessment, but I couldn’t leave her there. “I’d pay double the asking price,” I said, “just to get her away from this guy.” Janet was right about old injuries. There are deep scars on her legs. She favors her left shoulder and walks with an inconsistent gait. Janet thinks Miguel showed her in a charreada, or Mexican Rodeo. It’s comprised of nine events, including the manganas, or horse tripping, where a rider on horseback chases a horse around an arena, lassoes her legs, and makes her trip and fall.

Janet was right about old injuries. There are deep scars on her legs. She favors her left shoulder and walks with an inconsistent gait. Janet thinks Miguel showed her in a charreada, or Mexican Rodeo. It’s comprised of nine events, including the manganas, or horse tripping, where a rider on horseback chases a horse around an arena, lassoes her legs, and makes her trip and fall.  Lily’s psychological scars run deep, too. When she arrived in Hidden Hills, she was afraid of me. She shrank from my raised hand and wouldn’t let me touch her. I kept trying, and after a few days, she calmed down enough to let me stroke her neck and rub her back.

Lily’s psychological scars run deep, too. When she arrived in Hidden Hills, she was afraid of me. She shrank from my raised hand and wouldn’t let me touch her. I kept trying, and after a few days, she calmed down enough to let me stroke her neck and rub her back. On one of my visits with her, I found a small hard knot low on her shoulder and another one higher up. The vet found more of them under her tail. “She has melanoma,” he said. Melanoma tumors are common among gray horses, he told me. Many of them live normal lives without adverse effects, but the tumors can sometimes be fatal, spreading to vital organs, swelling up, and bursting open. “There’s no cure,” he said, “but there’s a vaccine that can slow the tumors’ growth. It’s expensive, and it often doesn’t work. Most people just ignore the condition and hope the horse outlives it.”

On one of my visits with her, I found a small hard knot low on her shoulder and another one higher up. The vet found more of them under her tail. “She has melanoma,” he said. Melanoma tumors are common among gray horses, he told me. Many of them live normal lives without adverse effects, but the tumors can sometimes be fatal, spreading to vital organs, swelling up, and bursting open. “There’s no cure,” he said, “but there’s a vaccine that can slow the tumors’ growth. It’s expensive, and it often doesn’t work. Most people just ignore the condition and hope the horse outlives it.” After all the training, she still gave me some good scares on solo rides. She calmed down over time and I feel safe now when I ride her, but I know fear was burned into her soul with a hot branding iron leaving a scar that can’t ever heal entirely. So, I ride her with vigilance and care, and I’ll never put my grandchildren on her back.

After all the training, she still gave me some good scares on solo rides. She calmed down over time and I feel safe now when I ride her, but I know fear was burned into her soul with a hot branding iron leaving a scar that can’t ever heal entirely. So, I ride her with vigilance and care, and I’ll never put my grandchildren on her back.  I love my horses and a lot of horses that aren’t mine. They all tug at my heart, but sometimes Lily tugs a little harder. She still startles when I approach her too quickly or raise my hand too suddenly. In those moments, she looks at me the way she did that first time I saw her tied to the tree in Miguel’s backyard, and I know she still remembers Miguel, the charreada, and the magnanas.

I love my horses and a lot of horses that aren’t mine. They all tug at my heart, but sometimes Lily tugs a little harder. She still startles when I approach her too quickly or raise my hand too suddenly. In those moments, she looks at me the way she did that first time I saw her tied to the tree in Miguel’s backyard, and I know she still remembers Miguel, the charreada, and the magnanas.