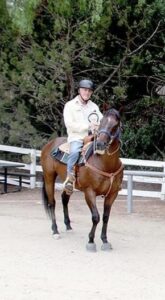

Riding Wilson

Last month, when the farrier lifted Wilson’s right back hoof to shoe him, the twenty-year-old thoroughbred lost his balance and almost fell. Having seen this before in older horses, the farrier ran his hand along Wilson’s neck and back, and as he expected, he flinched and nipped at him.

We called the vet. He stood beside Wilson’s hindquarters and pulled his tail toward him. Wilson swayed, then stumbled. “The normal reaction,” the vet said, “is for the horse to brace against the tugging force and hold his position. Wilson can’t do that because he’s not sure where his back legs are.”

Arthritis in his neck had damaged nerves running down his spine to his legs. Arthritis is incurable and relentlessly degenerative. “All we can do,” the vet said, “is slow down the skeletal deterioration.”

He prescribed prednisolone. “If the drug works,” the vet said, “Wilson should be able to carry a rider bareback or with a swayback cushion under the saddle for a few more years.”

The next morning, I dissolved 400 milligrams of the drug in water, mixed it with oats and molasses, and spread it over Wilson’s alfalfa. Later in the day, Janet, my trainer and good friend, riding her horse, Jesse, ponied Wilson while I followed on Marge. Wilson struggled, especially on the downhill slopes. When we finished up, he was sweating; his head was down; and he was drooling. Even a riderless walk had broken him down.

That was a watershed moment for me. I knew then that I would never again allow anyone, including me, to climb on Wilson’s back. Even if the drug worked, I wouldn’t take the chance of inflicting more pain on him.

It’s the right decision, but I’ll miss my rides with Wilson.

I first saw him almost four years ago on a home-made sales video. A young woman lunged a handsome, glossy bay in a dirt corral in Bakersfield, then rode him on a bareback pad over a dusty road. Doing his best to ignore a trio of mutts scurrying around his feet, Wilson followed the young woman’s cues, carefully backing up, standing still, and moving forward, to enable her to open a gate without dismounting.

I liked his demeanor. The way he held his head and the look on his face gave me the sense he was a good soul, trying hard to do his job well. The asking price was low and the young woman agreed to trailer him to Hidden Hills without charge, so I bought him.

She delivered him on a cool, clear February evening, and Janet and I walked him up the hill on Clear Valley Road toward my barn. A big, tall horse, a little under sixteen hands (about five feet four inches from the ground to his withers, the spot where his neck joins his back), his dark brown neck and head framed by a peach sunset, his black mane and forelock riffling in a light breeze, his head held high, his eyes alert, he looked around anxiously at the residential homes and manicured lawns.

When you buy a horse like Wilson, with no papers or pedigree, you know nothing about his history, what he’s been through, or how he’s been treated. More than likely, Wilson passed through many owners’ hands, some who were good to him and others who were cruel. Jane Smiley, the Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, wrote that such a horse’s life is like “twenty years in foster care, or in and out of prison, while at the same time changing schools over and over and discovering … that what you learned at the old school hasn’t much application at the new one.”

That passage ran through my mind as I watched Wilson prance nervously up the street. Earlier that afternoon, he stood on a drought-parched farm where everything was familiar to him. Without warning, the young woman came along, put a halter on him, and loaded him into a small, cramped tin box. For the next two and a half hours, he jounced around inside the metallic stall, as it rocked and swayed over freeways at seventy miles per hour, speeding him away from everything he’d ever known. When the trailer finally stopped, the young woman clanged open the rear door, backed him down a ramp, and handed his lead line to people he’d never met in a place where all the sights, sounds, and scents were completely foreign to him. Headed up the hill toward my barn that evening, he had to be lost and frightened by the sudden, radical change we’d forced upon him, and yet I sensed he was trying hard to adjust to this new world.

We led him into his stall. He walked around apprehensively, checking out the gray stucco walls and the wood shavings on the floor. He drank from the water bucket, then looked out the Dutch stall-door, taking in the street below, the valley, and the opposite ridge. We gave him orchard grass and alfalfa, and he attacked it like he hadn’t been fed for days. When I left him an hour later, he’d calmed down a little and seemed to be settling in.

His name on the bill of sale was Chippy. It didn’t fit. I’m not sure why, but the name Wilson came to mind when I was with him that night in the barn. I went with it, and it took hold.

A few days after Wilson’s arrival, we put him in the corral with his stablemate, Margarine, a little sorrel alpha mare. She hates most other horses. She tolerated Wilson for about an hour before attacking him. I ran a fence down the middle of the corral to keep the peace and called the vet to tend to Wilson’s bruises. For a more detailed account of their dust-up, see Animal Pharm.

The vet said Wilson was physically sound, but older than we thought. The young woman said he was twelve. The vet said he was sixteen or older. I didn’t care. I wanted a trail horse who would be good with my grandkids, and he fit the bill.

Janet spent the next few weeks training him, and he adapted to the neighborhood streets and trails quickly. I first rode him that spring. He wasn’t a comfortable ride. His walking gait was irregular, choppy, and bumpy, and his trot was like sitting on a jackhammer, but I liked riding him anyway.

Horseback riding presents a thrilling paradox. When you climb in the saddle, you must take a measure of control over your mount, but sitting on a twelve-hundred-pound animal, you give up a lot of control at the same time. Wilson’s tall frame and big barrel encase extraordinary power, and his speed lives up to his breed. My awareness of his power and speed made riding him exciting each time we went out. He turned out to be a gentle giant, though. He was always a safe ride except once when he reared for reasons beyond his control. See For the Love of Horses for a description of that incident.

Janet determined early on that Wilson was “cold backed” (sensitive to weight on his back until he was warmed up). We lunged him for a long time before each ride to compensate for that, but the steep downhills still seemed to strain his back, so we rode him on flatter trails.

Looking back on it now, I feel guilty about some of those rides. He must have been suffering, especially during the more recent outings, but he did whatever I asked of him, always giving his best effort, never balking or faltering.

About five days into Wilson’s treatment with prednisolone, the drug worked its magic. When I arrived at the barn that morning to feed him, he ran up the hill to his stall like a young horse. When we ponied him that day, the pain seemed to be gone, but I haven’t changed my mind. I know too much about arthritis. It crippled my knees until they were replaced, and I still have it in my fingers. Medication eases the pain for a while, but it always returns. Wilson’s been through enough. His riding days are over.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.

I’m told that some owners would dispose of an older horse in Wilson’s condition, dump him on a rescue organization, or send him to a kill-pen. I can’t do that. Wilson did his job well for as long as he could. Now I’ll do mine. I’ll keep him healthy, happy, and safe for the rest of his life.

Post Script: “Take care of your horses and treasure them.” Jane Smiley

July 14, 2022 @ 11:06 am

Another touching and informative personal account of your life experience. Well done! I shared Wilson’s story with my wife Stacy, who has had a lot of experience with her own horses before I met her 12 years ago. She will add a few words too: Hi Ken, I’m so moved by your journey with Wilson and grateful my husband shared it with me! What resonates for me

are memories of my first childhood horse “Little Man”, a 13 hand tri-color pinto gelding who I would credit with shepherding me through childhood and adolescence. He would come running through the pasture to greet me, I would jump on his back and we were off for the days’ adventure. I think the hardest part about going off to college was leaving him behind. I have often reflected that having completed “his work”, he could peacefully die as he did my first Quarter of college. I have shared my life with many special horses, but Little Man helped shape my life.

Wilson and Little Man set a high bar.

Thank you for sharing this part of your life !

July 14, 2022 @ 1:01 pm

Hi Bob and Stacy! Great to hear from you again, Bob, and I’m so happy to meet you, Stacy. Little Man’s story is wonderful. He sounds very special indeed! Thanks so much for sharing his story. I wish I’d found the love of horses early in my life, as you did, but I guess it’s for the best that I did not. I’d probably be a bankrupt saddle bum today with no wife, kids, or grandkids. We’ve been ponying Wilson since I wrote this piece. That right back leg gives him some trouble on the downhills, but all in all, he’s doing pretty well. I’m hoping he still has many good years ahead of him. Thanks for sharing my blog with Stacy, Bob, and thanks so much, Stacy for your comment!

July 4, 2022 @ 11:27 am

Thanks Ken. I know nothing about horses but so enjoy your article. Good luck with Wilson.

July 5, 2022 @ 7:29 am

Thanks, Ursula. He seems to be doing better. Enjoyed your posts from Iceland. You take the best vacations!

July 3, 2022 @ 2:01 am

You gave your horse, Wilson, a voice. You understand him. I, too , have a dearly beloved horse that I can no longer ride but he brings so much joy to me. Your story touches the heart. Thank you.

July 3, 2022 @ 8:00 am

Thanks so much, Colleen. You told me about your horse some time ago. You’re a good owner. I’m trying to be one, too.

July 1, 2022 @ 9:04 pm

Deeply touching Ken…brought tears

July 2, 2022 @ 6:59 am

Thanks, Janet! I imagine you read this with a perspective close to mine because you know the horse so well.

July 1, 2022 @ 7:49 pm

My old mare could no longer take an adult rider, but she absolutely loved the kids. Four year old would be trying to get her to run, but she gave them a faster walk. Some of the little girls just loved her to pieces. The older kids were deemed too big at about 9 or 10 because she started tripping when giving them a trot. I loved that mare and kept her until the colon cancer made her miserable. Then we did the kind thing and I still get wt-eyed thinking about it. Old dogs and old horses are special entities that give us way more than we give them.

July 1, 2022 @ 8:01 pm

Great to hear from you again, Janet. Thank you for sharing your memories. You are so right about old dogs and old horses! It is so hard to say good-bye when the time comes. They mean so much to us! Your mare sounds so special!

July 1, 2022 @ 1:52 pm

I love that you “get it” about horses. Horses came to me late in life, thank you Pamela and I just love them, my feathers is a beautiful soul and I will always take care of him . I am his final home and he will have a good life.

July 1, 2022 @ 2:47 pm

Well, I found my way to horses a lot later in life than you, but I’m glad I finally got here. Take good care of Feathers, as Jane Smiley tells us!

July 1, 2022 @ 1:21 pm

Wonderful tale. Resonates as we walk the same path as Wilson. ❤️

July 1, 2022 @ 2:44 pm

Thanks, Sonja. So true.

July 1, 2022 @ 12:27 pm

You have a kind compassionate heart Ken! I admire you for sticking with Wilson. ❤️

July 1, 2022 @ 2:43 pm

Thanks, Polly. I don’t have a choice. I couldn’t sleep at night if I let him down.

July 1, 2022 @ 12:05 pm

You have a warm gentle way with words as befits that beautiful and loving horse. I am in tears and have no more words but thank you

July 1, 2022 @ 12:22 pm

Thanks, Dianne, for your kind words. It hurt to give up riding Wilson, but writing about it helped.

July 1, 2022 @ 11:44 am

You’re the real deal, Ken. Lovely story about a great horse and owner. Thanks for sharing.

July 1, 2022 @ 12:19 pm

Thanks, Bob! He’s a great horse for sure.

July 1, 2022 @ 11:33 am

A wonderful story told in your wonderful way.

Please give Wilson some extra carrots from me — I’ll pay you back.

As always, thanks for sharing your story with us.

July 1, 2022 @ 12:18 pm

Thanks, Lucian. Hoping you can come see us soon. Wilson misses you. Marge, too!

July 1, 2022 @ 11:13 am

Thank you for giving Wilson a loving, forever home! As a fellow horse lover, I know that bond and how special it is. I’m wrestling with selling my 12 year old gelding that I’ve had for over 10 years and just can’t let him end up in a bad situation.

July 1, 2022 @ 11:45 am

I’ve only been a horse person for four years. I’ve never had to sell one. It must be gut wrenching. Good luck with it and thanks for your kind words.

July 1, 2022 @ 10:56 am

<3 <3 <3

July 1, 2022 @ 11:42 am

Thanks, Pamela!

July 1, 2022 @ 10:27 am

Lovely story as always…the part about the foster care resonated with me as Red had at least four owners before us, one of whom wasn’t nice to him. I promised him when we got him we would never give him up and we intend to keep that promise. We’ve had to move him several times, but always with his herd and his trainer, so he’s never been that disoriented. You know he started in Hidden Hills! Second owner I believe.…lucky Wilson!

July 1, 2022 @ 11:42 am

Thanks, Cindy. I remember you told me Red was here for a while. Charlotte says he’s a great horse. She loves him. Jane Smiley has written a novel and some great pieces about horse, but that little jag about foster care opened my eyes about what horses endure. We expect so much from them. It’s amazing that they so often deliver everything we ask. I’m fairly certain Wilson was treated very badly by previous owners, which may have caused his arthritis, but he remained a good horse through it all.

July 1, 2022 @ 10:13 am

Thanks Ken! What a thoughtful, loving description of Wilson.

July 1, 2022 @ 11:36 am

Thanks, Al. It was easy to write. Straight from the heart.