Staying Alive at 75

I turned 75 this month.

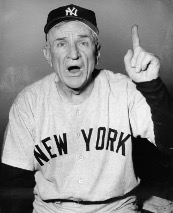

When Casey Stengel was 75, he said, “Most of the people my age is dead. You can look it up.” I did. He was right. In 1965 when he made that statement the average age of death in the U.S. was 70. For men it was 67.

I was surprised to find that Casey’s pronouncement comes close to holding true today. Even with all the advances in healthcare, the average age of death for U.S. men is now only 76.

That doesn’t give me much breathing room, so to speak, but at least I’m still alive on that mortality table. Using an actuarial analysis focusing solely on the life expectancy of men born in 1947, I’m already dead. I passed away in 2012 when I was 65. Fortunately, I didn’t notice.

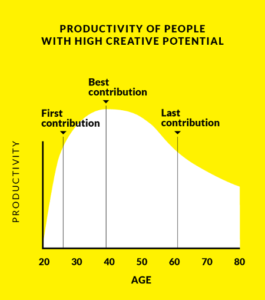

Researching perspectives on aging for this post, I found an article even more troubling than the death charts. In “Why I Hope to Die at 75,” Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel asserts that the optimum age to die is the three-quarter-century mark. He says our healthcare system has succeeded in finding ways to extend life but has failed to delay the onset of disabilities and disease. We live longer only to suffer longer. At 75 he believes most people are headed into a steep physical and cognitive decline, rendering them incapable of making valuable contributions to society. “(F)eeble, ineffectual, and pathetic,” they inflict a crushing financial and emotional burden on their kids and grandkids. To spare himself and everyone else the misery of his descent into infirmity, he intends to commit a passive suicide by rejecting preventive healthcare measures and life-saving procedures after his 75th birthday.

Dr. Emanuel’s credentials make it difficult to dismiss his dour view of aging. An internationally renowned oncologist and bioethicist, he is the University of Pennsylvania’s Vice Provost, Chair of its Medical Ethics and Health Policy Department, was an architect of Obamacare, and currently serves as a senior adviser to the Biden administration on Covid-19.

Dr. Emanuel’s credentials make it difficult to dismiss his dour view of aging. An internationally renowned oncologist and bioethicist, he is the University of Pennsylvania’s Vice Provost, Chair of its Medical Ethics and Health Policy Department, was an architect of Obamacare, and currently serves as a senior adviser to the Biden administration on Covid-19.

He also seems to be a good guy with a loving family and a lot to live for. He was 57 when he wrote his article. He’ll turn 65 this fall, so I hoped growing older might change his opinion about life after 75.

It did not. In a recent interview, he held fast to his original premise, and when questioned about examples of people who are mentally and physically capable and productive well past 75, he discounted their contributions. Such “outliers” are “a very small number,” he said, “and when I look at what those people ‘do,’ almost all of it is what I classify as play … They’re riding motorcycles; they’re hiking … that’s not a meaningful life.”

Not a meaningful life.

Three days before Christmas five years ago, I woke up in the middle of the night with a searing pain in the upper right quadrant of my abdomen beneath the ribcage. It spread upward to my shoulder and became so intense I had to stretch out on the floor on my back with my arms over my head to breathe. I pushed through the pain, and it went away at sunrise.

“It was no big deal,” I told Cindy.

“Call the doctor,” she said. “Now.”

When she uses her steely tone of voice, I do what I’m told. I slunk into the doctor’s office that afternoon. He said my symptoms indicated a gall bladder infection, a common problem, easily treatable. He ordered an ultrasound to confirm his diagnosis.

I lay on my back while a technician moved a hand-held transducer over my abdomen and chest, up, down, and across. The doctor said the ultrasound would take fifteen minutes. The technician kept at it for an hour.

The doctor called me at eight-thirty that night, well past his quitting time. “You have a gall bladder infection,” he said, “but not the normal type. The ultrasound indicates you have Acalculous Cholecystitis.” He said I had to see a gastrointestinal surgeon the next day.

“On Christmas Eve?” I said, alarmed. “How serious is this?”

“It requires immediate attention.”

I pressed him. Reluctantly, he disclosed the fatality rate for this condition as 30 to 50 percent.

I didn’t sleep that night.

The gastrointestinal surgeon, a middle-aged sandy-haired guy with a big nose and wide mouth, was skeptical of the ultrasound. Acalculous Cholecystitis usually attacks people suffering from another serious disease, cancer or heart failure. I had no other illness. He ordered more tests.

Strapped to a gurney in the hospital’s nuclear medicine department for three hours, I watched streams of multicolored fluids on a monitor above me as they coursed through my digestive system. The test results confirmed the ultrasound’s diagnosis.

They wheeled me into the operating room at five o’clock on Christmas Eve. An anesthesiologist, a tall balding man with a reassuring smile, pumped the contents of a syringe into my I.V. “Here comes the good stuff,” he said.

My last thought as the lights dimmed was a drug-blunted fear that I might not wake up.

I was under for two hours.

A spindly crack in an off-white ceiling came into focus. I heard tapping beside me. I looked over to see a heavy-set young orderly dressed in hospital blues working at a computer. He looked up. “You’re back,” he said.

“How do you feel, Dad?”

I turned to see my son standing beside my bed.

Behind him sitting at a desk by the wall, my surgeon gave me thumbs up. “Your gall bladder was gangrenous,” he said. “I got it all.”

I sobbed. “Thanks for saving my life,” I choked out.

“It’s the drugs,” the orderly told my son. “Makes them emotional.”

It wasn’t the drugs. It was the stupendous joy of being alive.

A week later, the results of my gall bladder’s biopsy came back. They found an infinitesimally small gallstone buried in the gangrenous tissue. All the tests had missed it. It had caused the infection. The diagnosis had been wrong from the start. I never had Acalculous Cholecystitis. I had a normal gall bladder infection. The only way it could have killed me was if I had refused to undergo the surgery to remove it.

A week later, the results of my gall bladder’s biopsy came back. They found an infinitesimally small gallstone buried in the gangrenous tissue. All the tests had missed it. It had caused the infection. The diagnosis had been wrong from the start. I never had Acalculous Cholecystitis. I had a normal gall bladder infection. The only way it could have killed me was if I had refused to undergo the surgery to remove it.

I’m glad I didn’t know that at the time. Thinking I might die gave me an appreciation for the blessings that were to come in the days still ahead of me. If I hadn’t survived the infection, here’s some of what I would have missed.

Granddaughter number 1 blossoming into one of the top fifty soccer players in the nation in her age group. Granddaughter number 2, also an elite soccer player, standing at the front of her fifth-grade classroom on grandparents’ day, telling everyone about fun times with Papaw. Granddaughter number 3 falling in love with horses at three years old and becoming an expert rider at seven. Grandson number 1’s precocious talents as a karate warrior, skateboarder, railroad enthusiast, and studio artist. The births of grandsons 2 and 3, both wild and crazy guys now three years old, one a future offensive lineman for the LA Rams, the other destined to become a world-class heavy-equipment operator.

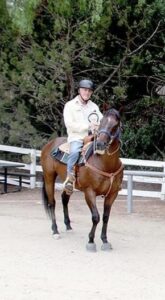

I would have missed building a horse barn, taking up horseback riding, bonding with Marge, Lily, Wilson, and Jackson, and the equine therapy of a thousand trail rides.

I would have missed the heart-swelling exhilaration and quiet satisfaction of crafting the plot and character interplay in The Judas Murders, the celebration of youthful first love in The Princess of Sugar Valley, and the cathartic self-realizations in Keeping the Promise and 20 more blog posts since its publication.

I would have missed watching my younger daughter marry and build a happy family with the love of her life, my son’s careful expansion of his prosperous business without skipping a beat in his role as a loving father and husband, and my older daughter and her husband achieving international acclaim and commercial success for their art gallery.

I would have missed watching my younger daughter marry and build a happy family with the love of her life, my son’s careful expansion of his prosperous business without skipping a beat in his role as a loving father and husband, and my older daughter and her husband achieving international acclaim and commercial success for their art gallery.

I would have missed five more years of love and companionship with Cindy along with the chance to become her caregiver and coach through two years of painful recoveries from double knee replacements, a small installment on my great debt to her for fifty-three years of support and encouragement, propping me up and keeping me going through good times and bad.

This is the short list. The full list of what I would have missed in the past five years would fill more pages than all my novels combined.

I don’t consider my life meaningless. In many ways, it’s more meaningful today than ever before.

I won’t reject preventive healthcare measures and life-saving procedures now that I’m 75. I’ll take all I can get. Dr. Emanuel is a really smart guy, but on the subject of aging, I prefer the medical advice of the poet: “Do not go gentle into that good night,/Old age should burn and rave at close of day;/Rage, rage against the dying of the light.”

I could go on about the many gifts of growing older, but I’ll rein it in for your sake and close by updating words I wrote in this blog five years ago.

I’m 75 years old; I’ve lived a long full life; I’ve still got a good ways to go; and you ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.

There’s a mystical communion between a horse and a rider. I had that with Wilson. Although that part of our friendship is gone, our bond remains strong. I can still pony him, walk him on a lead line, groom him, give him carrots, and talk things over with him, just like before.