The Almost Perfect Murder

My new book, The Judas Murders, was inspired in part by a double murder case from the 1960’s. Here’s what happened in that case.

Dr. Carl Coppolino, an anesthesiologist, and his wife Carmela, a research physician, lived in an affluent seashore community in New Jersey in 1961 when, at the age of 30, Carl had a heart attack. Due to his poor health, he quit his job and began collecting disability payments while Carmela continued to work to support their lifestyle.

Colonel William Farber and his wife Marjorie lived across the street from the Coppolinos. In 1962, while Carmela was pregnant with Carl’s second daughter, Carl and Marjorie Farber plunged into a torrid sexual affair.

On the morning of July 30, 1963, Colonel Farber complained of chest pains. Carl thought he was having a heart attack and told him to go to the hospital. He refused to go and died that afternoon. Carl convinced Carmela to sign the death certificate, listing coronary thrombosis as the cause of death. There was no autopsy.

By 1965, Carl had suffered three more heart attacks. He and Carmela moved to Sarasota, Florida, hoping the mild climate would improve his health. Marjorie Farber also relocated and moved into the house next door to them.

In August, Carmela complained of chest pains. Carl awoke on the 28th to find that she had died in her sleep. He told Carmela’s doctor that she had a heart attack, and the doctor signed a death certificate indicating coronary occlusion as the cause of death. No autopsy was performed. Carmela was 32 when she died.

Shortly before her death, Carl had joined a bridge club. His regular playing partner was Mary Gibson, a wealthy divorcee. He married her twenty-two days after Carmela’s death.

Carl’s jilted mistress, Marjorie, was not pleased. She told the police Carl had murdered both their spouses. She said he helped her give Colonel Farber an injection of the anesthetic drug succinylcholine, but the shot didn’t kill him so Carl smothered him with a pillow. She claimed that Carl killed Carmela with the same drug.

Marjorie’s allegations made sense from a medical standpoint. Succinylcholine has benign purposes. Anesthesiologists use it to intubate patients prior to surgery, paralyzing the throat so a doctor can insert a breathing tube painlessly, but mega-doses of it are fatal. Veterinarians euthanize animals with it, and some states include it in a three-drug, lethal-injection cocktail to execute capital defendants.

Most importantly for a murderer, succinylcholine converts almost instantly after injection into metabolites that normally exist in the body. Until the 1990’s, there was no reliable method for determining in an autopsy that it was the cause of a victim’s death, making it the perfect murder weapon. As an anesthesiologist, Carl would have known this.

Based on Marjorie’s allegations, the courts ordered the exhumations of Colonel Farber and Carmela Coppolino. The medical examiner found no evidence of heart problems in either corpse. Both states indicted Carl for murder.

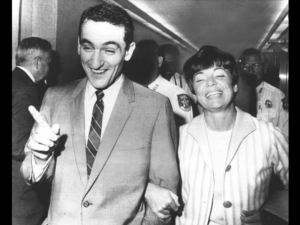

The New Jersey trial went forward in 1966 with F. Lee Bailey as Carl’s attorney. Farber’s body had been in the ground for more than two years when the autopsy was performed. Its results were ambiguous. The medical examiner could not find succinylcholine in the corpse and he couldn’t testify with certainty that Farber had been smothered. The prosecution depended almost entirely on Marjorie’s testimony. In a savage cross-examination, Bailey portrayed her as a “woman scorned,” who would say anything to take revenge on Carl. After only four hours’ deliberation, the jury found Carl not guilty.

The Florida trial in 1967 about Carmela’s death was a different story. The prosecutors based the case on objective circumstantial evidence, rather than Marjorie’s testimony. A doctor testified that he gave Carl six vials of succinylcholine a few weeks before Carmela’s death because Carl said he needed the drug for research, although Carl was not a licensed doctor at the time. Carl increased his benefit under Carmela’s life insurance policy just before she died. Her medical records contained no history of heart problems. Carmela turned down Carl’s request for a divorce shortly before her death, and Carl’s bridge club members said that he moved in with Mary Gibson the day after Carmela died.

The forensic evidence was stronger, too. The medical examiner spotted a puncture in Carmela’s buttocks consistent with a syringe wound and found abnormal levels of the metabolites derivative of succinylcholine in her organs.

After only six hours’ deliberation, the jury found Carl guilty of second degree murder. Technically, the verdict made no sense. Poisoning requires pre-meditation and planning, but second degree murder is an intentional killing that is not premeditated. Bailey filed vigorous appeals based on that inconsistency and on a host of other legal issues.

The appeals were unsuccessful, but Carl’s wealthy second wife, Mary, somehow convinced a Florida legislator overseeing the parole board that Carl was innocent, and the board released him in 1979 at the age of 47, after serving 12 years.

The next year, Carl published a book entitled The Crime that Never Was. It begins with Carl and Mary making love in bed in the Buccaneer Motel the morning before the Florida jury rendered its verdict. A three hundred page daily diary of Carl’s jail time follows, salted with rants about his vicious persecution. He claims the medical examiner manufactured the forensic evidence against him, Bailey committed malpractice, the Florida judge and prosecutors knew he wasn’t guilty, his jailers were sadistic, and so on. He doesn’t address the events leading up to the deaths of Colonel Farber and Carmela or attempt to explain the circumstantial evidence against him. In The Crime That Never Was, Carl, and not Carmela, is the victim, a martyr burned at the stake of a corrupt justice system.

I don’t think so. Based on the evidence adduced at the trials, I think he was a narcissistic cold-blooded murderer. That evidence, coupled with the known effects of succinylcholine on the body, tell us exactly how he killed Carmela. He plunged a syringe into her hip while she lay in bed. He held her down while she struggled against him for the one to three minutes it took for the Clydesdale–size dose of succinylcholine to kick in. Then she lay still, the drug having paralyzed every muscle in her body. For the next three to five minutes, she was trapped inside a living corpse, fully conscious, but immobile and helpless, even unable to move her eyes, as her diaphragm froze up and her breath grew shorter and shorter until she couldn’t breathe at all. Through it all, she knew exactly what was happening to her, right up to the moment of her death.

Knowing full well as an anesthesiologist what the drug was doing to Carmela, Carl stood over her and coldly watched the woman he had met and married in medical school, his wife of nine years, and the mother of his two daughters die a horrific death by his hand.

Post Script: Carl died in 2017 at the age of 84. There was no autopsy. Too bad. I wonder if a medical examiner would have found evidence of those five heart attacks Carl claimed to have suffered fifty years before he died, back when he was too sick to work but well enough for red-hot sexual liaisons with Marjorie and Mary.