My Great-granddaddy

On a cold winter day, our Hudson pitched and rolled over a rutted red-clay road and stopped in front of giant boxwood bushes flanking a brick walkway. Dad cut the engine and we sat staring at a big old two-story farmhouse.

“How bad off is he?” Mom said.

“They had to move his bed down to the parlor,” Dad said. “He’s too weak to climb the stairs to the bedroom.”

“You think he’ll get well this time?”

“I don’t know.”

Sitting in the back seat, I hung on every word. One of my earliest memories is walking with Dad and Great-granddaddy through a mowed cornfield on a sunny fall day, dried corn husks crunching under our tread. In his late twenties wearing a mustard-colored hunting jacket, Dad carried a shotgun for bird hunting. Great-granddaddy was five-eight with a full head of snow-white hair and a handlebar moustache, his back straight, his stomach flat. When we came to a three-rail fence, Dad climbed over it and reached back to lift me across. When he set me down, I looked up to see Great-granddaddy jump off the top rail, land on his feet, and stride on ahead of us. Dad smiled. “Your Great-granddaddy is one tough old boy,” he said to me. “Eighty-eight and strong as a horse.”

My great-grandparents owned a tobacco farm outside Appomattox a couple miles from Lee’s surrender to Grant at the home of Wilmer McLean, who had moved his family south to escape the Civil War when the Union Army shelled his farm in northern Virginia in 1861 at the beginning of the conflict, only to have the Yankees seize his Appomattox home for General Grant’s headquarters in 1865 at the end of it.

Snapshot memories of our visits to my great-grandparents’ farm have stayed with me through the years. Sleeping in a big feather bed, feeding chickens and gathering eggs with Great-grandma, a broken-down Model A Ford squatting in a spider-webbed corner of a shed, a snake’s skin nailed to the weathered planks of an old barn, elephant-ear-sized tobacco leaves hanging from its rafters, a tall coal-black horse feeding on hay in his stall.

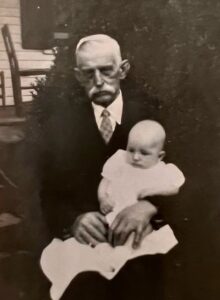

In my mind’s eye, I can still see Great-granddaddy dressed in a three-piece black suit sitting tall in the saddle on that big roan. I remember him walking me up the porch steps, his calloused hand gripping my hand so tightly it was all I could do not to cry out in pain. Also emblazoned in my memory is the time he met us at the foot of the steps when we arrived, picked me up like I weighed nothing, held me in his arms, and looked at me gravely. “Kenneth William Oder,” he said in a gravelly voice.

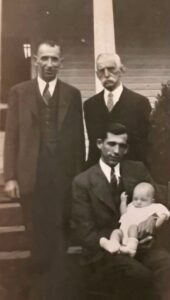

In a photograph Mom took in 1947 when I was four months old, Dad is seated in a chair holding me. Behind him stand my Granddaddy and my Great-granddaddy. Dad and Granddaddy are smiling. Great-granddaddy’s expression is stern, the same grave look he gave me a few years later when he picked me up and said my full name. On the back of the photo Mom wrote, “Oder family, 4 generations.” Looking back on it now with the perspective of age, I think his expression conveyed pride, pride in heading up the family’s four generations and pride in me, not because of anything I’d done, but simply because I existed, a great-grandson he’d lived long enough to hold in his arms.

We lived near Yorktown in those days. The trip from our house to Appomattox traveled over winding country back roads. The rides were long and boring for me, but when Dad talked to Mom about Great-granddaddy, I perked up.

He had lived on the Appomattox farm all his life, Dad said. His father was a wheelwright in Lynchburg when he met Arianna Cheatham. They married, bought the ninety-acre farm, and raised six sons on it. Great-granddaddy was the third son, born in 1862 during the Civil War. His brothers left the farm when they grew up, but he stayed on. After his father’s death, he bought out their inherited interests, married Lizzie Coleman, a daughter of the County Sheriff, and they farmed the land for the next half-century.

Dad told stories about Great-granddaddy’s strength and fearlessness. He once killed a copperhead by picking it up by its tail and cracking it like a whip. He walked tirelessly behind a horse plowing fields from sunup to sundown. He tossed around bales of hay like they were matchboxes and lifted stalks of tobacco like they were little twigs. He never drank a drop of liquor; he never smoked a cigarette; and he went to church every Sunday.

Dad told stories about Great-granddaddy’s strength and fearlessness. He once killed a copperhead by picking it up by its tail and cracking it like a whip. He walked tirelessly behind a horse plowing fields from sunup to sundown. He tossed around bales of hay like they were matchboxes and lifted stalks of tobacco like they were little twigs. He never drank a drop of liquor; he never smoked a cigarette; and he went to church every Sunday.

Somewhere along the way, the old man became an iconic hero in my toddler mind. He was invincible, I thought. He’d live to be 100. Maybe even older.

So, when we sat in our Hudson staring at the old farmhouse that cold morning, I knew Great-granddaddy would get well, despite what Dad said.

When we walked in the parlor, Great-granddaddy sat in a rocker in front of a big bed, wearing long-john underwear and muddy black work boots with a shawl draped across his shoulders. His face was pale; his eyes rheumy.

Dad leaned over and hugged him. “You look good, Granddaddy!”

Mom kissed him on the forehead and laughed. “You look mighty fine. I bet you been actin’ like you’re sick just to get attention!”

He didn’t respond to Mom and Dad. He didn’t smile. He didn’t return their hugs. I touched his knee, but he didn’t look at me.

Mom and Dad sat in straight-backed cane chairs near the woodstove. I sat in a little rocking chair between them. Great-grandma sat next to the old man. She apologized for his appearance. She said he’d wanted to put on his Sunday go-to-church suit before we came, but he wasn’t strong enough to pull on his pants and she couldn’t manage dressing him by herself. It took all her strength just to help him out of bed to the rocking chair.

While she talked, I stared hard at Great-granddaddy. He wheezed with every labored breath, his shoulders slumped, his eyes downcast.

“He tries to get up on his feet,” Great-grandma said, “but he can’t do no good. He can’t walk. Can’t take a step.”

As she spoke, Great-granddaddy raised his head and looked at me. A slight smile lifted the corners of his snow-white moustache.

I recall only disjointed images of what happened after that, but Mom remembered every detail and told the story every chance she got.

I walked over to the old man. “It’s not true you can’t walk. You’re my Great-granddaddy. You can do anything.” I grabbed the fingers of his big rough hand with both my hands and pulled on him. “Come on, Great-granddaddy! Get up! You can walk! I know you can!”

Grunting and straining against his weight, I pulled as hard as I could. “Stand up, Great-granddaddy!” He leaned forward uncertainly, tried to stand, but fell back. I pulled harder. He rocked his chair forward, swung his head out over his knees, and stood up slowly and unsteadily.

I tugged him toward the opposite wall. He took a faltering step, righted himself, and took another. And another. We made it across the room. I turned and pulled him back toward Great-grandma. He staggered along behind me. When we got to her, I turned and pulled him toward the opposite wall again. Halfway across I broke into a run. He shuffled along to keep up with me, his boots clomping on the plank floor. We ran back and forth three or four times before I finally tired out and let go of him.

He collapsed in the rocker, gasping for air, every breath rattling in his chest like marbles banging around inside a tin can.

He collapsed in the rocker, gasping for air, every breath rattling in his chest like marbles banging around inside a tin can.

I jumped up and down in front of him, cheering. “I knew you could do it, Great-granddaddy! I knew you could do it!”

He looked at me with big tears rolling down his cheeks and that slight smile fighting its way through.

He got well shortly after our visit.

It wasn’t part of Mom’s story, but I remember Great-grandma staring at me wide-eyed that day. She was a woman of faith. She believed God had worked a healing miracle through me. Mom thought so, too.

When I was a little boy, I didn’t think it was a miracle. I believed Great-grandaddy could do anything, so I wasn’t surprised when he stood and walked, but as I listened to Mom tell the story over the years, I came to realize it was, at a minimum, a miracle of courage, rock-hard grit, and indomitability. Running across that room almost killed him, but he refused to let me down no matter what it cost him.

He wasn’t invincible. He didn’t make it to 100. He died of heart failure at 92. No one can beat time forever, but he sure-to-God gave old age a good long hard fight.

Thomas William Oder (1862–1954). My Great-granddaddy. A strong man of good character and iron will. A role model for a worshipful toddler. One tough old boy.

One morning a couple of days before my 74th birthday, I stepped on something partially buried in the dirt in my horse corral. I picked it up and turned it over in my hand. A porcelain round wafer the size of a lollipop mounted on a five-inch-long metal rod. Etched in black letters on its off-white surface: “NOT DEAD YET.”

One morning a couple of days before my 74th birthday, I stepped on something partially buried in the dirt in my horse corral. I picked it up and turned it over in my hand. A porcelain round wafer the size of a lollipop mounted on a five-inch-long metal rod. Etched in black letters on its off-white surface: “NOT DEAD YET.”

She lived in a trailer in the woods with her mother, Lottie. Lottie was in her mid-fifties, short and stumpy with a weathered face, hearty laugh, and wide smile sporting a gap where her upper front teeth should have been.

She lived in a trailer in the woods with her mother, Lottie. Lottie was in her mid-fifties, short and stumpy with a weathered face, hearty laugh, and wide smile sporting a gap where her upper front teeth should have been.