Life or Death

The first case I studied in law school was Georgetown College v. Jones. This is what happened in that case.

In 1963, a twenty-five year old mother of an infant child suffered a ruptured ulcer. Her husband, Jesse Jones, took her to a hospital in Washington, D.C., operated by Georgetown College. The doctors said Mrs. Jones would die unless they administered blood transfusions. Jesse refused consent. He and his wife were devout Jehovah’s Witnesses. Certain verses in the Bible prohibit the drinking of blood, which the Joneses interpreted to mean that blood cannot be used for human consumption by any means. They believed that a blood transfusion was tantamount to drinking blood.

The hospital felt responsible for Mrs. Jones’s life. It hired lawyers to seek an emergency court order granting the doctors permission to perform the transfusions without the Jones’s consent. The lawyers met with U. S. District Court Judge Edward A. Tamm. He denied the request on the grounds that a court order would violate the First Amendment’s protection of the Jones’s religious beliefs.

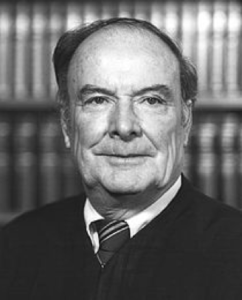

The hospital’s lawyers rushed to Judge J. Skelly Wright of the District of Columbia Circuit Court of Appeals for a review of Judge Tamm’s decision.

Appellate court judges almost always make their decisions based on the written record in the court below. Judge Wright broke from that convention. He telephoned the doctors at the hospital and verified that Mrs. Jones would die without the transfusion. He went to the hospital and tried to convince Jesse to grant consent. Jesse refused. The judge spoke with Mrs. Jones. She was so far gone that the only words he could make out were “against my will.”

Father Bunn, Georgetown’s President, made a fervent theological argument to Jesse that a transfusion was not “drinking blood” within the meaning of the Bible verses. Jesse stood firm and refused consent.

When Mrs. Jones’s ruptured ulcer brought her to death’s doorstep, Judge Wright made his decision. He signed an order giving the doctors permission to perform the transfusions; the doctors took immediate action; and Mrs. Jones survived.

In his written opinion, Judge Wright doesn’t cite a case directly on point or other authority. The closing words of his written opinion explain the basis for his decision. “There was no time for research and reflection.… I determined to act on the side of life.”

On the first day of law school, we discussed this case for an hour. The professor then asked how many of us agreed with Judge Wright’s decision. It seemed clear to most of us. All but one raised our hands in agreement with Judge Wright.

At the end of the year on the last day of that same class, the professor went over Georgetown College v. Jones with us again and asked the same question: “How many of you agree with Judge Wright’s decision?” No one raised a hand.

“What happened to you people?” he said, smiling. But he knew. We all knew. Our first year in law school had forever changed us. We had learned to think like lawyers.

What does learning to think like a lawyer mean? To the general public, it seems to mean becoming a heartless scum bag, as in: Why do surgeons prefer to operate on lawyers above all other patients? Answer: They have no heart and their butts and heads are interchangeable. And along the same line, what’s the difference between a vacuum cleaner and a lawyer riding a motorcycle? Answer: The vacuum cleaner has the dirt bag on the inside. (This is a stupid joke, by the way. I’ve never seen a lawyer on a motorcycle.)

Jokes aside, thinking like a lawyer has gotten a bum rap. To me, it merely means applying the law to a set of facts with reason and logic and without regard to emotions, preconceived notions, or prejudices. Sometimes that works a result that appears heartless but it is actually sensible in the long run.

In Jones, Judge Wright’s order saved Mrs. Jones’s life only by overriding her religious beliefs. At first blush, it appears to be the right decision emotionally, but a time-honored saying among lawyers is that hard cases make bad law. Judge Wright’s decision in these sympathetic circumstances may be cited as authority in the next case for the government to take away a citizen’s right to worship, or not, as they choose. His decision in this hard case could make bad law in the next.

It might not even be the right decision emotionally. Mrs. Jones believed that blood transfusions would defile her body. Suppose she lived out her life believing she was unclean and would burn in hell for eternity because she “drank blood.” Perhaps this was a fate worse than death in her eyes. Better to set the emotions aside and make a reasoned decision on the law.

So I raised my hand against Judge Wright’s decision after I’d been taught to think like a lawyer.

But the world turns. Thirty years after law school, I held a position as a company executive. One morning, a man I’d never met showed up in my office in tears. He told me he thought we planned to eliminate his job, so he found another job and resigned. Under our healthcare plan, he could have chosen to pay the premium for our coverage and we would have kept it in place until his new employer’s insurance picked him up. He decided not to pay and the coverage lapsed.

His new employer changed its mind and decided not to hire him. Shortly after that, he was diagnosed with cancer. Without treatment, he would die within a few months. With treatment, he would have a fighting chance. He didn’t have the money to pay for the treatment, so he begged us to reinstate his healthcare coverage. We were self-insured so we didn’t have to consult with an insurance company. The decision was ours alone. Our benefits department had turned him down. He begged me to overrule them.

He waited outside my office while I spoke with the Benefits Director. In tears herself, she said, “We can’t do it. The Plan’s language is clear. He missed the window to extend by a mile. If we give him coverage, the precedent may expose us to frivolous claims.”

I’d heard this story before. Hard cases make bad law.

I combed through the plan’s language. I pointed to a phrase in the small print. “What about this?”

“It doesn’t work,” she said. “It doesn’t apply.”

She was right, but I read the phrase several times, trying to find a way to stretch it to reach the man’s situation. Finally I said, “I think it applies,” and I signed the document to extend the coverage.

The greatly relieved Benefits Director took the man downstairs to fill out the forms he needed to get treatment, and I never saw him again. I learned the following year that he fought hard but lost his battle.

How do I reconcile my hand-vote in the Jones case with my signature on that form? I don’t know. All I can say is you kind of had to be there.

That’s the lesson of the Jones case, too, I suppose. Judge Tamm rendered his decision from chambers, surrounded by legal tomes. Judge Wright went to the hospital, talked to Jesse Jones, and watched the light fading from a young mother’s eyes while she lay on her death bed. Looking into people’s eyes can screw you up. The statutes, case law, and plan language tend to fall away. Before you know it, you end up thinking like a human being, for pity’s sake.

April 27, 2017 @ 5:48 am

Great story Ken.Thanks for letting us in on how Lawyers really think!Case closed.

April 27, 2017 @ 9:19 am

Thanks, Larry!

April 25, 2017 @ 6:12 pm

You are amazing, Ken. Great tale.

April 26, 2017 @ 8:09 am

Thank you, Pamela!

April 25, 2017 @ 4:00 pm

Every time I read one of your posts I think more of you. Wow, that was no exception. I am grateful to have worked in a career where there is less gray, where it is easier to make decisions since they can typically be based on logic and data. I cannot imagine and would really struggle with the decisions faced by Lawyers and Judges every day.

PS. The Joke about the motorcycle was pretty great too!.

April 26, 2017 @ 8:08 am

Thanks, Eric! That joke’s the reason I don’t own a motorcycle.