Hillary Care

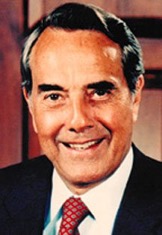

Senator Bob Dole rubbed his swollen jaw. “Tooth’s killing me,” he barked. “Headed to the dentist.” He gestured toward a young woman standing behind him. “Suzie can tell you all you need to know about …” He frowned at me. “Remind me again what you’re here for.”

“Hillary Care,” I said.

He waved his hand in the air dismissively. “Nothing to worry about. It’s dead in the water.”

“We support the bill, Senator.”

He scowled. “Well, it won’t get a single Republican vote!” He winced and grabbed his mouth. “You tell em what-for, Suzie.” And he hurried out the door.

Standing in the Senate Minority Leader’s office beside Safeway’s CEO and its Senior VP of Public Affairs, I stared balefully at the empty doorway, Senator Dole’s toothache having torpedoed an hour-long meeting we’d scheduled weeks earlier. Not an auspicious start to our trip to the Hill, I thought, worried that this day might turn out to be a career limiting experience.

Labor relations was one of my areas of responsibility at Safeway. The company’s contracts with the United Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) union required us to provide Cadillac healthcare coverage to our store employees. Our nonunion competitors didn’t offer healthcare, giving them a huge cost advantage which they used to undercut our prices. They were killing us.

Safeway’s CEO made the pragmatic decision to support Hillary Care because it would level the playing field. We were skeptical that the bill would actually pass, but we thought we could gain a side benefit by supporting it. The UFCW was a major proponent of the legislation. By joining hands with the union, we hoped to improve our rocky relationship and enhance our credibility about cost reductions at the bargaining table.

We scheduled a full day of meetings at the Capitol Building to lobby for Hillary Care, starting with Senator Dole. After he vamoosed for the dentist, I presented our arguments to Suzie, his staffer. She disagreed with every point I made, ending with, “The last thing we need is politicians deciding what a broken leg is worth.” Senator Dole’s opposition remained firm.

We trundled down the hall to Idaho’s Senator Larry Craig. You may remember him. An undercover policeman arrested him in the men’s bathroom of an airport for passing a note under the stall soliciting a sexual encounter. The senator claimed he had a wide stance when squatting, saw the note beside his shoe, and picked it up out of curiosity. He resigned from the Senate in disgrace, but that was a decade after our meeting with him. In the early 90’s, wide-stance Larry still wielded a lot of clout. He must have been up late the night before our meeting (doing God knows what) because he nodded off about half-way through my electrifying presentation. Out number two.

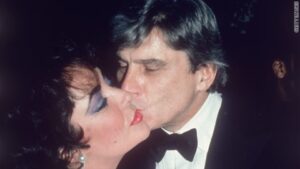

My parents had met Virginia Senator John Warner and his wife, Elizabeth Taylor, at a clam bake on the Northern Neck. Dad didn’t like him. Mom didn’t like his movie-star wife because of her track record with husbands (the senator was her seventh marriage) and her wardrobe at the clam bake. “Somebody ought to tell that woman she’s gained too much weight to traipse around in tight jeans.”

My parents had met Virginia Senator John Warner and his wife, Elizabeth Taylor, at a clam bake on the Northern Neck. Dad didn’t like him. Mom didn’t like his movie-star wife because of her track record with husbands (the senator was her seventh marriage) and her wardrobe at the clam bake. “Somebody ought to tell that woman she’s gained too much weight to traipse around in tight jeans.”

At least my parents got to meet the senator. He didn’t grace us with his presence, sending his chief of staff in his place. I made my pitch. He looked at me like I was a Russian spy and showed us the door.

On a roll by then, I whiffed with Senators Kempthorne and Gorton.

I was 0 for 5 when we talked to Senators Rockefeller and Feinstein. They said they were in favor of the bill, but that didn’t improve my batting average. They’d announced their support for it months earlier. The way things were going, I was relieved that nothing I said turned them against it.

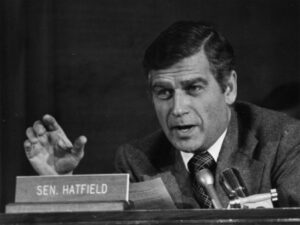

We closed the day with Oregon’s Senator Mark Hatfield. He’s generally forgotten now, but he was a big deal in his day. Insiders say Richard Nixon’s choice for VP at the 1968 G.O.P. convention came down to Hatfield and Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew. Nixon chose Agnew. A bribery scandal forced Agnew to resign during Nixon’s second term, and Gerald Ford took his place as VP. I’ve often wondered what the world would be like today if Nixon had chosen Hatfield and he had succeeded Nixon to become our 38th President.

We closed the day with Oregon’s Senator Mark Hatfield. He’s generally forgotten now, but he was a big deal in his day. Insiders say Richard Nixon’s choice for VP at the 1968 G.O.P. convention came down to Hatfield and Maryland Governor Spiro Agnew. Nixon chose Agnew. A bribery scandal forced Agnew to resign during Nixon’s second term, and Gerald Ford took his place as VP. I’ve often wondered what the world would be like today if Nixon had chosen Hatfield and he had succeeded Nixon to become our 38th President.

When we met with him, he was a grandfatherly 72, dressed in a blue shirt and red suspenders that flanked a little potbelly. When I finished my presentation, he leaned back in his chair and smiled. “I’ll tell you how this will play out.” Hillary Care would receive no Republican support, he said, and Senator Dole would block it from coming to the floor with the filibuster rule. As time dragged on, Democrats would jump ship and propose compromise bills. None would gain momentum, and universal healthcare would die without a vote in the senate.

And that’s exactly what happened. Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell declared the final compromise bill dead on September 26, 1994.

And that’s exactly what happened. Senate Majority Leader George Mitchell declared the final compromise bill dead on September 26, 1994.

Although Hillary Care failed, we achieved the better relationship with the UFCW we had hoped for and our contract negotiations were less contentious from there on.

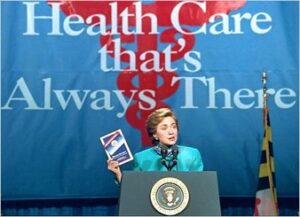

An unexpected byproduct of our efforts came along later when the President of the UFCW invited me to a luncheon with President Clinton and a small group of his supporters. These affairs usually require a huge campaign donation, so I begged off. “Can’t fit it into the budget,” I told him.

“You won’t have to pay,” he said.

“What’s the catch?”

“No catch. The President wants to thank Safeway for its help with healthcare.”

The luncheon took place at billionaire Ron Burkle’s Beverly Hills estate. Safeway’s VP of Public Affairs and I walked up a serpentine driveway to a massive mansion where Secret Service agents searched us before we were admitted to a spacious dining room that was obviously way above my pay grade.

President Clinton entered from a side door and worked the room, spending one-on-one time with the thirty attendees. When he came to me, he beamed and thanked me for Safeway’s help. I’d heard that some politicians have a charismatic magnetism, but I’d never experienced it. I did then. I wasn’t a fan of President Clinton before or after that luncheon, but when I was in his presence, talking with him about our daughters going off to college, I felt a powerful gravitational pull into his orbit that I didn’t expect or understand. I wanted to like him. I wanted to believe in him.

President Clinton entered from a side door and worked the room, spending one-on-one time with the thirty attendees. When he came to me, he beamed and thanked me for Safeway’s help. I’d heard that some politicians have a charismatic magnetism, but I’d never experienced it. I did then. I wasn’t a fan of President Clinton before or after that luncheon, but when I was in his presence, talking with him about our daughters going off to college, I felt a powerful gravitational pull into his orbit that I didn’t expect or understand. I wanted to like him. I wanted to believe in him.

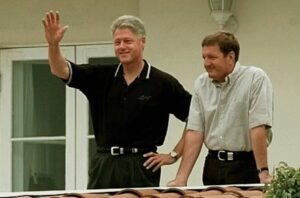

After the luncheon, he stopped on his way out of the room to speak to me again. He said he might make another run at expanded healthcare. I offered our help. I heard cameras clicking as he shook my hand. The call for help never came, but photographs of the handshake arrived in the mail.

Thinking I’d impress my parents with what a big wheel I’d become, I sent them the photograph of me shaking hands with the President. On our next call, Dad’s first words were “I hope you washed your hands after they took that picture.”

In the end, my foray into the political world on behalf of Hillary Care left me kind of cold. President Clinton was by far the most talented politician I met, and he turned out to be spectacularly flawed. Looking back on those days now, I’d say Dad’s pithy hygienic advice made good sense in the political arena even before Covid-19 came along.

In the end, my foray into the political world on behalf of Hillary Care left me kind of cold. President Clinton was by far the most talented politician I met, and he turned out to be spectacularly flawed. Looking back on those days now, I’d say Dad’s pithy hygienic advice made good sense in the political arena even before Covid-19 came along.

Post script: I met President Clinton once more years later. I’d heard he had an astounding memory for people he’d encountered only briefly. The rumor was true. He remembered my name and I felt that pull again, at least until I got out of the room.

August 1, 2020 @ 5:14 pm

I just live your folks reactions.. Dear folks… true Virginians…

August 2, 2020 @ 8:07 am

They weren’t big on pretension and always seemed to get straight to the heart of a matter.

August 1, 2020 @ 7:16 am

I met President Clinton when he spoke at a Latham partners’ meeting. He did have a magnetism that few people possess. I had a small group breakfast with Hillary Clinton while she was still trying to push through the health care bill. She was smart and engaging and had zero magnetism.

August 1, 2020 @ 8:03 am

I’ve heard the same reaction to both Clintons from scores of people, who met them. I was mystified and a little bit afraid of this magnetic quality. I’d never experienced it before, nor have I since then. Pretty strange, but a great gift for a politician.

July 31, 2020 @ 3:56 pm

You look like a deer in the headlights! Great story, as usual.

July 31, 2020 @ 7:57 pm

Yeah, I was pretty shook up.

July 31, 2020 @ 12:14 pm

I recall hearing about the events!

July 31, 2020 @ 1:08 pm

It was a wild day. But there were many back in those days!

July 31, 2020 @ 12:03 pm

Ken. Enjoyed your humorous way of describing your experience with the senators — and President Clinton. Interesting to think how things would be different if Hillary Care had passed. And how much hand washing you would need to do today if you met with our current roster of senators!

July 31, 2020 @ 1:07 pm

Thanks, Lucian. I’d be scrubbing furiously!

July 31, 2020 @ 11:37 am

Nice one Ken. If we ever get together (hope you’ll come to Florida!) I’ll tell you about Teddy Kennedy losing my wife’s car!

July 31, 2020 @ 1:06 pm

Thanks, Chad. I hope you got that car back somehow. If this Pandemic ever plays out, Cindy and I may head that way.

July 31, 2020 @ 11:13 am

Your Dad sounds like someone I would like.

July 31, 2020 @ 1:04 pm

He was a wise man. He would have liked you and Jack, too. I wrote a blog about him years ago. If you have time and want to check it out, google “The Preacher Ken Oder” and it will come up at the top of the search list.

July 31, 2020 @ 11:09 am

Ken, don’t you thank your lucky stars that your Corporate life is behind you now. Hope all is well and stay safe. Best, Jim

July 31, 2020 @ 1:01 pm

It was fun when we were involved in it, but I don’t miss it now. You stay safe and well, too.