Voting Angst

Politics makes me sick. Literally. On election day in 2016, I woke up feeling nauseous. I blew breakfast mid-morning and ripped through a series of dry heaves that afternoon. Exhausted, I collapsed on our living room recliner.

“I’m really sick,” I told my wife as we watched the election coverage. “I must have food poisoning.”

“I don’t think so,” Cindy said. “We both ate the same things. Maybe it’s the election.”

I stared at the obnoxious talking heads yammering away on the television screen and thought she might be on to something.

We live in California. It’s basically a one-party state. The California Republican Party has been on life support for a decade. By 2016 there were more California voters registered as Unaffiliated than as Republicans. Democrat victories became so routine that even the Democrat-controlled state legislature got bored with the process. To create competitive contests in November, it amended California election laws to pit the top two vote-getters in the open primaries, almost always Democrats, against each other in the general election.

You might think like-minded candidates from the same party would run clean campaigns. Think again. In 2012, redistricting forced two Democrat incumbents to run against each other for the 30th District of the House, which covers the San Fernando Valley where I live. Having served ten terms, Howard Berman was Chairman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee. Brad Sherman had served seven terms and sat on the same committee.

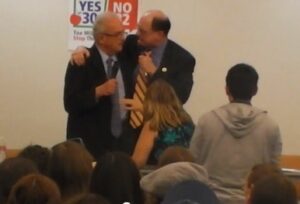

Good friends when the campaign started, they shared almost identical voting records. Unable to find much to disagree about on policy, their pitch to the voters quickly devolved into increasingly bitter personal attacks, culminating in a televised physical altercation on the debate stage at Pierce College. When Howard accused Brad of being “delusional,” he lost it. Brad crossed the stage, grabbed Howard by the shoulders, and jammed his nose in his face. “You want to get into this?” he shouted. A sheriff’s deputy and the debate moderator jumped between them and pulled Brad away.

Brad’s campaign manager claimed Howard started it by stepping toward Brad in a threatening manner. It strained credulity. Resembling a bald-headed Big Bird, Brad is taller and thirty pounds heavier than Howard and Howard was 71 years old at the time. Despite the televised assault, Brad won by twenty points, sending poor Howard to the political boneyard. A harbinger of things to come.

The pukey contest in 2016 was the national Presidential election. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump ran relentlessly negative campaigns with her basket of deplorables and his rally chants of “Lock her up.” I felt like a rat poised at the head of a T‑shaped Skinner Box with both metal bars at opposite ends of the T set to deliver a high voltage shock no matter which lever I pulled.

The pukey contest in 2016 was the national Presidential election. Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump ran relentlessly negative campaigns with her basket of deplorables and his rally chants of “Lock her up.” I felt like a rat poised at the head of a T‑shaped Skinner Box with both metal bars at opposite ends of the T set to deliver a high voltage shock no matter which lever I pulled.

On election night, I thought my angst about that god-awful choice had made me sick, but my upset stomach turned out to be an early symptom of an infected gall bladder that spent the next two months trying to kill me. The doctors cut it out on Christmas Eve and I fully recovered, but with next Tuesday rolling inexorably toward us, my nausea has returned. Since my gangrenous gall bladder is long gone, the 2020 election seems the likely culprit this time.

My queasiness began with California’s new voting process. The state mailed ballots to all voters this year so we could vote without risk of exposure to Covid at a polling place. We can mail our ballot or deliver it to a California drop box at designated civic locations.

In a desperate attempt to increase their voter turnout, the small band of remaining California Republicans created their own ballot boxes, labeled them “Official,” and placed them in strategic locations across the state. The Democrats went ballistic. The state Attorney General, Xavier Becerra, a Democrat, launched an investigation.

In a desperate attempt to increase their voter turnout, the small band of remaining California Republicans created their own ballot boxes, labeled them “Official,” and placed them in strategic locations across the state. The Democrats went ballistic. The state Attorney General, Xavier Becerra, a Democrat, launched an investigation.

The Republicans defended their boxes as permissible “ballot harvesting.” The Democrat-controlled legislature passed a law several years ago allowing campaign workers and party officials to collect ballots from voters and take them to the polls. Republicans screamed bloody murder at the time, accusing Democrats of legalizing voter fraud, but this year they apparently decided to push the envelope of the new rules by harvesting ballots in private drop boxes.

Becerra filed suit seeking a cease and desist order, and the Republicans are fighting the case. They removed the “Official” label, but they insist the boxes otherwise comply with the law. As I write this, thousands of ballots are suspended in legal limbo inside those boxes.

Worse yet, a creative soul invented a new voter suppression technique based on the design of the real California drop boxes. The state constructed them with heavy metal so no one could penetrate them and tamper with the ballots. Knowing that, an arsonist in Baldwin Park jammed burning paper through the ballot slot. While smoke belched from the mouth of the box, citizens on the scene couldn’t break into it to rescue its contents. By the time the fire department cut it open with a metal saw, more than a hundred ballots had burned to a crisp. Election officials are trying to figure out how to identify the voters and give them replacement ballots. Good luck with that.

Even if I manage to cast my ballot safely, my vote won’t make much difference. Most of the contests are lopsided; their outcomes foregone conclusions. The only dogfight is the race for LA County District Attorney. The incumbent, Jackie Lacey, is the first woman and first African American to serve in that position since its creation in 1850. She’s running on her two-term record. Her challenger, George Gascon, is a former LAPD Assistant Chief and former San Francisco District Attorney, who supports police reform and the elimination of cash bail.

Lacey looked like a shoo-in until she got crosswise with Black Lives Matter. Upset with some of her decisions not to prosecute police officers accused of racial violence, forty BLM protesters gathered in front of her home before dawn on March 2 and shouted for her to come outside. When she didn’t respond, three of their leaders went to the front door and rang the doorbell. Lacey’s husband came to the door brandishing a gun. “I will shoot you,” he said. “Get off my porch.” Attorney General Becerra filed criminal misdemeanor charges against him, and BLM leaders filed a civil suit alleging assault and infliction of emotional distress. The race is now a toss-up.

The 2020 presidential contest presents another high voltage Skinner Box. Trump says Biden is a crook who’s lost his marbles. Biden says Trump is a crook who never had any marbles in the first place. The way things have gone so far in 2020, they’re both probably right.

Meanwhile, Brad Sherman is coasting to reelection in my district for his thirteenth term. I’ve voted against Bellicose Brad four times since he beat up on old Howard. I’m voting against him again this time but it won’t do any good. He seems destined to be my representative in Washington until one of us dies. Nothing personal, but I hope he kicks the bucket first.

This morning I marked, sealed, and signed my ballot, drove to the Calabasas City Hall drop box, looked around furtively for arsonists lurking in the weeds, then shoved my vote through the slot.

I haven’t thrown up yet, but it’s not over. With the uncertainties of the process and both presidential campaigns gearing up for legal challenges, I’ll be chugging Pepto Bismol all the way to Inauguration Day.

I haven’t thrown up yet, but it’s not over. With the uncertainties of the process and both presidential campaigns gearing up for legal challenges, I’ll be chugging Pepto Bismol all the way to Inauguration Day.

Postscript: Apparently, I’m not alone. The American Psychological Association reported last week that 68% of American adults currently suffer from Election Stress Disorder. Symptoms include loss of sleep, sudden irritability, and, of course, an upset stomach.

Mom pulled our Rambler to the curb on a rainy fall afternoon. I sat in the passenger seat, feeling queasy.

Mom pulled our Rambler to the curb on a rainy fall afternoon. I sat in the passenger seat, feeling queasy.

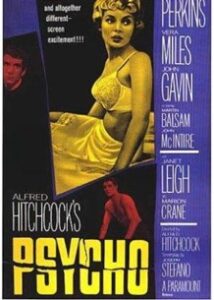

“That woman gets stabbed in the shower,” Richard said. “It’ll scare the crap out of the girls. Gerry will probably jump in your lap. Even a doofus like you ought to make it to first base after that.”

“That woman gets stabbed in the shower,” Richard said. “It’ll scare the crap out of the girls. Gerry will probably jump in your lap. Even a doofus like you ought to make it to first base after that.” In my head, I saw all the boys in the eighth grade massed up at my homeroom desk, pointing at me, laughing, and shouting, “Doofus!”

In my head, I saw all the boys in the eighth grade massed up at my homeroom desk, pointing at me, laughing, and shouting, “Doofus!” Marcia jumped into Richard’s arms. Gerry put her hands over her face. Arthur patted her on the shoulder gently and seemed to be trying to comfort her. Ann didn’t move a muscle. Neither did I.

Marcia jumped into Richard’s arms. Gerry put her hands over her face. Arthur patted her on the shoulder gently and seemed to be trying to comfort her. Ann didn’t move a muscle. Neither did I. I realized too late what was wrong. The movie chairs were designed for adults. Being short, I had to raise my arm above my shoulder to reach the high back. All the blood was draining out of my arm. Worse yet, I was trapped in that position. If I took my arm off the chair, Richard would tell everyone, and I’d never live it down.

I realized too late what was wrong. The movie chairs were designed for adults. Being short, I had to raise my arm above my shoulder to reach the high back. All the blood was draining out of my arm. Worse yet, I was trapped in that position. If I took my arm off the chair, Richard would tell everyone, and I’d never live it down. When the movie ended and we walked out of the theater, my arm hung off my shoulder like a piece of dead meat.

When the movie ended and we walked out of the theater, my arm hung off my shoulder like a piece of dead meat. “Trying to get the blood to come back,” I said under my breath, clenching and unclenching my fist.

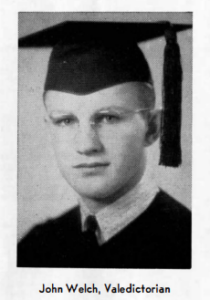

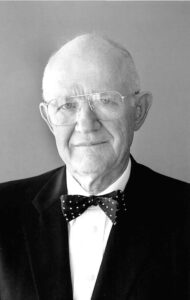

“Trying to get the blood to come back,” I said under my breath, clenching and unclenching my fist. On August 9, John Welch, a Latham & Watkins retired partner, celebrated his 100th birthday with his children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren, an astounding 104 direct descendants in all. In his long life, he has positively influenced the lives of thousands of people. I’m one of them.

On August 9, John Welch, a Latham & Watkins retired partner, celebrated his 100th birthday with his children, grandchildren, great grandchildren, and great great grandchildren, an astounding 104 direct descendants in all. In his long life, he has positively influenced the lives of thousands of people. I’m one of them.