Zoey’s Song

At four in the morning our Pit Bull, P.D., stood on his hind legs with his front paws on my bed and nuzzled my arm with his nose. He and Zoey, our American Bulldog, usually sleep through the night, but they wake me to let them out if they need to go to the bathroom. As soon as I get up P.D. usually races down the stairs to the back door, but that night he walked over to his bed and laid down.

At four in the morning our Pit Bull, P.D., stood on his hind legs with his front paws on my bed and nuzzled my arm with his nose. He and Zoey, our American Bulldog, usually sleep through the night, but they wake me to let them out if they need to go to the bathroom. As soon as I get up P.D. usually races down the stairs to the back door, but that night he walked over to his bed and laid down.

I went to the bedroom door. “You wanna go out or not?”

P.D. didn’t move.

Cursing under my breath, I went back to sleep. P.D. woke me again. When I got up, he returned to his bed.

“What the hell’s going on?”

P.D. just stared at me.

Exasperated, I went back to bed. He jumped up, walked over to Zoey’s bed, and sat down. When I looked at Zoey, I realized what P.D. had been trying to tell me. Uncharacteristically, she hadn’t stirred during his ups and downs. She lay on her side, her eyes closed, her tongue sticking out of her mouth. I knelt beside her. Her bed was sopping wet with urine. Semi-conscious, she couldn’t stand.

I made an emergency appointment with the vet. He gave her a complete physical.

“Is it kidney failure?” I asked.

“I don’t know. I’ll need to see the results of her blood panel to make a diagnosis.”

“What’s the treatment for kidney failure?”

He paused. “There’s no cure,” he said gently.

His words took my breath away. “How long has she got?” I choked out.

“We’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s wait for the blood work.”

On the drive home I fought back tears as Zoey slept on the seat beside me.

When she was five months old, a dog breeder who’d lost his home to foreclosure begged my daughter to take her for a few days, then disappeared, and wouldn’t answer her calls. My daughter already had three dogs. She asked Cindy and me if we wanted Zoey. A few years earlier, two fourteen-year-old dogs we’d raised from puppies succumbed to cancer. We turned Zoey down at first because we were still heartbroken, but we missed the love of a dog and we eventually agreed to take her.

When she was five months old, a dog breeder who’d lost his home to foreclosure begged my daughter to take her for a few days, then disappeared, and wouldn’t answer her calls. My daughter already had three dogs. She asked Cindy and me if we wanted Zoey. A few years earlier, two fourteen-year-old dogs we’d raised from puppies succumbed to cancer. We turned Zoey down at first because we were still heartbroken, but we missed the love of a dog and we eventually agreed to take her.

I had recently retired, and Zoey filled my suddenly empty days. When I walked her in the park, she bounced along like she had springs in her legs. She chased down tennis balls and leapt high in the air to catch frisbees. At night, we rolled around on the floor in front of the television, playing chew-toy tug of war. She followed me everywhere and waited for me at the front windows whenever I left home without her.

Time passed. We moved to Hidden Hills. To keep her safe from rattlesnake bites, I spent a small fortune on a snake fence to enclose our big backyard and took her to rattlesnake avoidance training. She was smart and learned her lessons quickly.

When our grandkids came over, she got excited and played too rough. Knowing Zoey was a quick study, I hired a dog trainer to break the habit. A nice young woman in her late twenties, the trainer was gentle with Zoey, but firm. Zoey didn’t like the firm part. She hid under the bed at the beginning of each session, and when I pulled her out in the open, she stood behind me and timidly peeked around my leg at the trainer.

When our grandkids came over, she got excited and played too rough. Knowing Zoey was a quick study, I hired a dog trainer to break the habit. A nice young woman in her late twenties, the trainer was gentle with Zoey, but firm. Zoey didn’t like the firm part. She hid under the bed at the beginning of each session, and when I pulled her out in the open, she stood behind me and timidly peeked around my leg at the trainer.

“We’re getting nowhere,” the young woman said. “Zoey’s not the problem. She’s smart. You’re the problem. She knows you’ll let her get away with anything. You won’t discipline her.”

The trainer was right. I spoiled Zoey. I still do. I can’t help it. It’s who I am.

I paid the trainer a bonus and terminated the lessons. Zoey miraculously got better with the grandkids on her own. That might have been a coincidence, but I like to think Zoey paid me back for getting rid of the trainer.

When Zoey turned five, we added P.D. to the family. It didn’t work out well at first. She was jealous and miserable whenever I paid attention to P.D. I asked the vet for advice. He said Zoey’s reaction to P.D. was typical of dogs who’d been the sole pet in a household for several years. “She doesn’t want to share you with another dog. She’s like an only-child toddler, who resents the attention her dad gives to a newborn baby. She’ll get over it with time, but my guess is she secretly likes him already. Spy on them when they’re alone. See how she acts.”

The vet was right. From the kitchen window where Zoey couldn’t see me, I watched her playing with P.D. in the backyard. They wrestled like puppies having the time of their lives. Zoey’s jealousy soon faded away, and she became good pals with P.D. even when I was around.

A few years later, arthritis crippled me so badly I couldn’t take Zoey and P.D. on their daily walks, so I hired our dog groomer to cover for me. Zoey didn’t want to leave the house without me. I had to shove her out the door, and at the end of her walks, she ran back to me. When I went through knee replacement surgeries to get back on my feet, Zoey kept vigil at the foot of my bed during my recoveries, and she was overjoyed when we hit the trails again.

The years rolled by, and age began to take its toll. The vet implanted metal screws in Zoey’s back knee to hold it together; arthritis ate away at her shoulders; and nascent cysts budded in her eyes. The vet prescribed Carprofen for arthritic inflammation and Keterolac eyedrops to keep the cysts at bay. Even with the medicine, Zoey’s eyesight dimmed, her gait became stiff-legged, and climbing steps grew difficult.

Despite her aches and pains, she seemed happy and remained active until the morning of our emergency trip to the vet. When we returned home, I placed a rubber pad under her dog bed. Listless and lethargic, she spent most of the day there. That night she fell into a deep sleep. Shafts of moonlight coming through the windows highlighted the fawn spots on her white back. Watching over her, I tried to come to grips with her mortality. I could not.

The vet called me the next day. “It isn’t renal failure,” he said. “The blood work is consistent with a treatable condition. Some female dogs, who were spayed young, suffer from weak bladders in old age. Zoey was spayed at five months.” He prescribed Proin to restore bladder control and ordered a more extensive blood panel to rule out other illnesses.

The medicine worked. Zoey’s energy and personality came back, and the blood analysis cleared her of everything else.

That all went down three months ago.

Since then, her brush with death has forced me to face up to a harsh truth. Zoey and I have grown old together, but time marches to a faster, meaner beat of the drum for her. The life expectancy for her breed is ten. She’s thirteen. A heart-breaking day lurks out there somewhere in the future. I have to accept it.

But for now, she’s still with me. She wags her tail when she wakes up in the morning, plays tug of war with her chew toys, jumps around like a puppy when I grab her leash, and enjoys the sights and scents of two walks a day. Our dog groomer, who knows more about canine health than most vets, thinks she has several good years ahead of her. I hope he’s right. In the meantime, I’ll savor the memories of our long, good run together and make the most of the fun times still to come.

Post Script: “Old age is the way of all living things. It’s natural and ordinary. All creatures are born, grow old, and die. There’s no point in crying about it.” I put those words in Jolene Hukstep’s mind in Old Wounds to the Heart. They seemed to help her, but when the day of loss came, she still cried.

For more about Zoey and P.D., see Dog Days, Rattlesnake Avoidance Training, Animal Pharm, and Coyote Run.

Every morning at dawn I walk down the driveway with my dog, Zoey, to get the newspaper. When we stepped outside one day a couple of years ago, a coyote stood in the front yard. Lean with a dirty gray coat, spindly legs, long snout, and pointy triangular ears, it lowered its head, and stared at us with piercing close-set eyes.

Every morning at dawn I walk down the driveway with my dog, Zoey, to get the newspaper. When we stepped outside one day a couple of years ago, a coyote stood in the front yard. Lean with a dirty gray coat, spindly legs, long snout, and pointy triangular ears, it lowered its head, and stared at us with piercing close-set eyes. Zoey is an American Bulldog, two feet tall at the shoulders, weighing 70 pounds. The average coyote is her height but less than half her weight. When Zoey was young, she would have been more than a match for any coyote, but she was eleven years old that day with arthritis in her front shoulders and an artificial back knee, so I wasn’t sure she could survive a fight with this one.

Zoey is an American Bulldog, two feet tall at the shoulders, weighing 70 pounds. The average coyote is her height but less than half her weight. When Zoey was young, she would have been more than a match for any coyote, but she was eleven years old that day with arthritis in her front shoulders and an artificial back knee, so I wasn’t sure she could survive a fight with this one. Zoey followed in hot pursuit. About half-way up, her arthritis finally got the best of her. She stumbled and fell, then scrambled to her feet, barking hysterically, but she was too weak to climb higher.

Zoey followed in hot pursuit. About half-way up, her arthritis finally got the best of her. She stumbled and fell, then scrambled to her feet, barking hysterically, but she was too weak to climb higher. Many of my neighbors’ pets have not been so fortunate.

Many of my neighbors’ pets have not been so fortunate. This absence of fear, referred to as habituation, is a dangerous phenomenon. Naturalists Rex Baker and Robert Timm, who studied coyotes in suburban and urban environments, observed seven stages of escalating aggressive behavior among habituated coyotes. Coyotes in my neighborhood have reached stage 5 – attacking pets on a leash or standing near an owner. If Baker and Timm’s study is an accurate predictor of coyote aggression, we need to reverse the progress of habituation before it reaches Stages 6 and 7, threatening actions toward children and adults.

This absence of fear, referred to as habituation, is a dangerous phenomenon. Naturalists Rex Baker and Robert Timm, who studied coyotes in suburban and urban environments, observed seven stages of escalating aggressive behavior among habituated coyotes. Coyotes in my neighborhood have reached stage 5 – attacking pets on a leash or standing near an owner. If Baker and Timm’s study is an accurate predictor of coyote aggression, we need to reverse the progress of habituation before it reaches Stages 6 and 7, threatening actions toward children and adults. Habituation has reached Stage 5 in countless neighborhoods and reports of attacks on pets are commonplace, but thankfully, attacks on people are rare. Baker and Timm’s study found 367 reported coyote attacks on humans over the four decades from 1977 through 2015. About half occurred in California. Children comprised 40% of the victims, adults 60%. Many of the attacks on small children appeared to be predatory and occurred during the mating and pup-raising season from March through August when coyote mates, who are monogamous for life, are sometimes desperate for prey to feed their young. Attacks on adults often involved people trying to defend their pets from a coyote mauling.

Habituation has reached Stage 5 in countless neighborhoods and reports of attacks on pets are commonplace, but thankfully, attacks on people are rare. Baker and Timm’s study found 367 reported coyote attacks on humans over the four decades from 1977 through 2015. About half occurred in California. Children comprised 40% of the victims, adults 60%. Many of the attacks on small children appeared to be predatory and occurred during the mating and pup-raising season from March through August when coyote mates, who are monogamous for life, are sometimes desperate for prey to feed their young. Attacks on adults often involved people trying to defend their pets from a coyote mauling. In another study of coyote attacks by Lynsey White and Stanley Gehrt, about half resulted in minor bite wounds. Predatory attacks and rabid coyotes accounted for most of the serious injuries.

In another study of coyote attacks by Lynsey White and Stanley Gehrt, about half resulted in minor bite wounds. Predatory attacks and rabid coyotes accounted for most of the serious injuries. Relocating them is also ineffective. They usually return to their original territory, and when they don’t, other coyotes move in and take over.

Relocating them is also ineffective. They usually return to their original territory, and when they don’t, other coyotes move in and take over. Baker and Timm believe that hazing may not work once a coyote has reached Stage 5, attacking pets in the presence of their owners. They recommend more drastic measures along with hazing to deter aggression at that stage, such as removal of members of the local coyote population through extermination or relocation, to send a message to the remaining pack.

Baker and Timm believe that hazing may not work once a coyote has reached Stage 5, attacking pets in the presence of their owners. They recommend more drastic measures along with hazing to deter aggression at that stage, such as removal of members of the local coyote population through extermination or relocation, to send a message to the remaining pack. I realize, though, that I might not hold that view if the fleeing coyote’s trap had worked a couple of years ago. If the coyote and its partner had killed Zoey. If I’d heard her death wails. If she’d died in my arms. Some of my neighbors have lost their pets that way. They disagree with me, and I can’t blame them.

I realize, though, that I might not hold that view if the fleeing coyote’s trap had worked a couple of years ago. If the coyote and its partner had killed Zoey. If I’d heard her death wails. If she’d died in my arms. Some of my neighbors have lost their pets that way. They disagree with me, and I can’t blame them. Tuesday night, August 2, lying in bed in his Hidden Hills home, Vin Scully, the legendary sportscaster, drew his last breath.

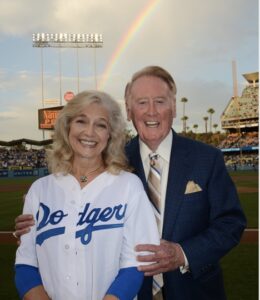

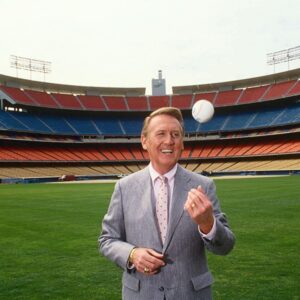

Tuesday night, August 2, lying in bed in his Hidden Hills home, Vin Scully, the legendary sportscaster, drew his last breath.

He was a living legend. He was voted national sportscaster of the year 4 times, California sportscaster of the year 33 times, sportscaster of the twentieth century, and the top-ranked sportscaster of all time. He received a Lifetime Emmy Award. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He was inducted into the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame, the NAB Broadcasters Hall of Fame, the National Radio Hall of Fame, the California Sports Hall of Fame, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In LA Straw polls we voted him the most trusted media personality, the most memorable person in Dodger history, and the biggest icon in LA sports history.

He was a living legend. He was voted national sportscaster of the year 4 times, California sportscaster of the year 33 times, sportscaster of the twentieth century, and the top-ranked sportscaster of all time. He received a Lifetime Emmy Award. He has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. He was inducted into the American Sportscasters Hall of Fame, the NAB Broadcasters Hall of Fame, the National Radio Hall of Fame, the California Sports Hall of Fame, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom. In LA Straw polls we voted him the most trusted media personality, the most memorable person in Dodger history, and the biggest icon in LA sports history. “Who’s Vin Scully?” I asked.

“Who’s Vin Scully?” I asked.

When we moved into Hidden Hills, I installed a second telephone line for business calls. The first time I answered its ring, a woman was in mid-conversation about a personal problem. When she paused, a man’s smooth tenor voice broke in, concerned, supportive, encouraging. I immediately recognized the speaker. He had talked to me for three decades.

When we moved into Hidden Hills, I installed a second telephone line for business calls. The first time I answered its ring, a woman was in mid-conversation about a personal problem. When she paused, a man’s smooth tenor voice broke in, concerned, supportive, encouraging. I immediately recognized the speaker. He had talked to me for three decades. AT&T sent out a big mean-looking guy with a sour disposition, who turned into a little kid with wide eyes and a shy grin when I told him Vin Scully owned the phone line he’d been assigned to repair.

AT&T sent out a big mean-looking guy with a sour disposition, who turned into a little kid with wide eyes and a shy grin when I told him Vin Scully owned the phone line he’d been assigned to repair. As our neighbor remarked the night of his death, he was always willing to talk at the mailbox. He always greeted me and Zoey on our dog-walks with a warm smile, and his friendliness eventually disarmed my reticence.

As our neighbor remarked the night of his death, he was always willing to talk at the mailbox. He always greeted me and Zoey on our dog-walks with a warm smile, and his friendliness eventually disarmed my reticence. He is irreplaceable. For almost seven decades, in our cars, living rooms, and bedrooms, at our kitchen counters and barbecue grills, beside our swimming pools on sunny summer days, he talked to us in an easy way like an old friend.

He is irreplaceable. For almost seven decades, in our cars, living rooms, and bedrooms, at our kitchen counters and barbecue grills, beside our swimming pools on sunny summer days, he talked to us in an easy way like an old friend.